Alison Saar

Lost and Found

(born 1956)

American 2003 Wood, tin, and wire 28 1/2 x 125 x 33 inches (72.4 x 317.5 x 83.8 cm)

Museum purchase with funds provided by the 2004 Medici Society 2004.16

New Life

Can found objects from daily life like chairs and ceiling tin teach us anything about gender and race? For Alison Saar such common items have a wisdom from years of use, a wisdom she channels into sculptures that explore aspects of what it means to be human.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Create!

A personal symbol is a sign that represents yourself to other people. Alison Saar’s personal symbol is hair in her sculptures. In Lost and Found, hair symbolizes Saar’s African-American identity. Artists have included their own personal symbol throughout the centuries in artwork.

To create your own personal symbol, think about your personality and interests. How might you represent them visually?

To start, pick a verb, an action word you like to do, and draw that action. It could be an activity you enjoy doing with your friends or family. Then choose an adverb, a word that describes your verb, and draw that. Finally, when both words are drawn, combine them by drawing one on top of the other.

Write a paragraph about your symbol and why you picked those words. Share your symbol and writing with a friend.

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

An Unusual Process

Although sculptors often explore ideas with preparatory drawings, Alison Saar prefers to make drawings of her sculptures after they are finished, such as the one below. Look closer at both the sculpture and the drawing and note how some details vary from the sculpture. Also consider how the three-dimensional sculpture and the two-dimensional drawing create different effects even though they depict similar objects.

Alison Saar (American, b. 1956), Lost and Found, 2003, charcoal, acrylic, and shellac on paper, 96 x 22 1/4 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Medici Society, 2004.17.

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

More than Meets the Eye

Lost and Found is made from commonplace materials, but their ordinariness may hold a variety of complex meanings. Explore one possible interpretation in the following audio clip with Will South, Chief Curator at The Dayton Art Institute from 2009 to 2011.

Transcript:

Alison Saar’s Lost and Found is a large and commanding sculpture; it grabs your attention right away. But, what could it possibly mean? We see two figures seated and looking straight down, each figure a mirror image of the other, connected only by a cloud of hair stretched out between them. One way to look at this work of art is as a visual metaphor. Though the figures do not look toward each other and sit opposite each other, they are connected; you might even say they are bound together, tied up together. The artist may be saying that what ties us together, literally, is more than what keeps us apart. The sculpture is made of nothing fancy: it is wood, tin and wire. The use of these simple materials suggests that this sculpture comes from the world of real daily life, made from the humble things we all know. This simplicity combined with the seemingly fantastic way the figures are presented supports the message the artist may be trying to send—that we go through the world connected to each other, however unlikely it may sometimes seem.

Look Around

Hair Styles

Look closer at the hair in Lost and Found. How would you describe it? What does it tell you about the two figures? Alison Saar often depicts hair in her artworks because it is a way to explore her African-American identity (see “About the Artist”).

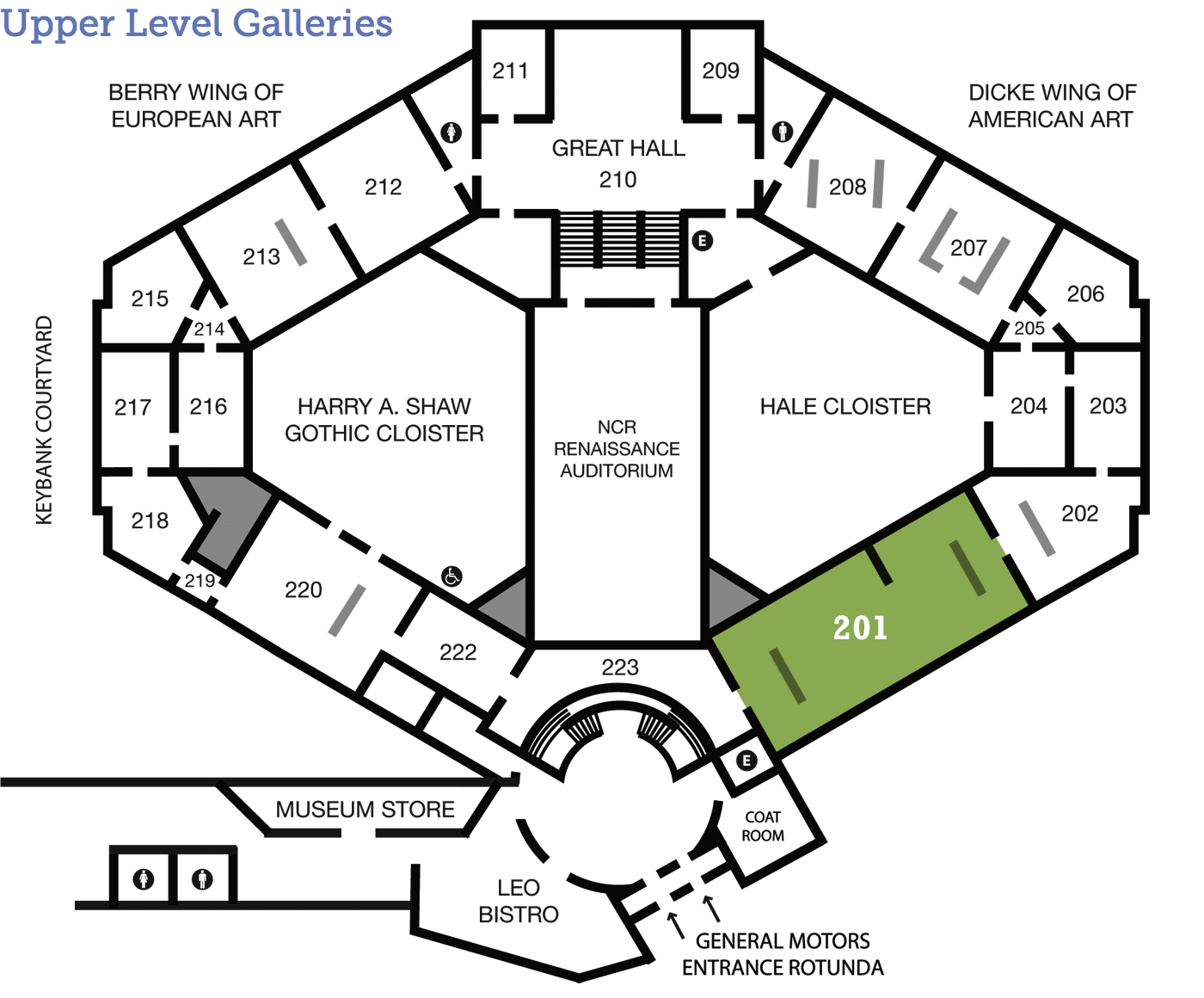

Look around at other ways hair is depicted in artworks at The DAI, such as the Chinese Head of Guanyin in Gallery 109, or Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Henry, 8th Lord Arundell of Wardour in Gallery 213. As you look at these and other examples, consider what sorts of things hair—whether color, texture, length, style, or decoration—may communicate about a person.

Chinese, Head of Guanyin, 11th–14th century, clay mixed with straw with traces of pigment, height: 25 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by Mrs. Harrie G. Carnell, 1959.41.

Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792), Henry, 8th Lord Arundell of Wardour, c. 1764–1767, oil on canvas, 94 x 58 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Price, Jr., 1969.52.

About the Artist

In her own words

What inspires Alison Saar to make sculptures like this? Find out as she talks about her interests in the topics of gender, race, age, and common daily life in the following video from the Otis College of Art and Design.

© Otis College of Art and Design 2008

I generally call myself a sculptor. I work in many medias but primarily sculpture, and then I do drawings and graphic prints as well. But the work generally deals with gender. Sometimes I’ve been titled a feminist artist. It deals with gender and race; it’s about being able to touch and feel things. I mean I’ve got my hands folded in my lap, but generally I speak with my hands and have to experience everything through my hands.

I think I first started doing sculpture when I was apprenticing with my father who’s an art conservator. And so he was always exposing me to the likes of classical Greek sculpture or sculpture of the Renaissance. My mother is an artist; she also introduced us to the art of non-Western cultures, so we were looking at Native American art and African art and Indian art, and so I think those things are deeply ingrained in what inspires me. I’m often considered Caucasian, and so for me, especially since I identified so strongly with my mother’s family, it was always a struggle to have my African-American heritage recognized. It seemed to me that the only part of me that really sort of reflected that was my hair. And so, a lot of times in my work I’ll exemplify the hair or have it be specifically about those sort of struggles: either trying to confine and control the hair and have it be more Caucasian or, on the other hand, just letting it go crazy and embracing it and having it take over the world.

I think that fascination of the found object and the found object having a sort of power to it, the found object having a history and a memory of its life and a wisdom, was really, really important to the early work, and I think it continues to be—maybe not so much as an object, but sort of the power and the integral sort of spirit of the certain materials are really important to me. In the last show, there’s a stack of found—or, well, purchased mostly—children’s chairs, and some of them are school chairs and some of them are nursery chairs and all of that, but I love the idea that all these children—many of them are from the 30’s and 40’s—had sat in these chairs passed on and on to different generations and have found this sort of little space in these little chairs.

If you look back 30 years—almost 30 years—of work, you can pretty much trace what sort of emotional trauma I was experiencing. Identifying as an African American and identifying as being black in the United States, residual circles from slavery and struggles still that are here right now in terms of inequities. And then the work, I think with the birth of my son in 89’, started taking on a real interest in issues of spirit and where spirits come from, where they go to and who are these young children that come into my life and how do I affect them and how do they affect me? And then also became really interested at that point in African deities. So, I got very interested in Yoruba religion and the pantheons within that. Then worked out a lot with the female body and then, as my body started to expand, I started talking about how women are judged by their bodies primarily; I did a whole series of women viewed from their backsides and women as specimens. And I think now, without being too crude, I’m dealing with “I’m now 52 and menopausal,” and I’m looking at my daughter who’s 14 and just now coming into womanhood. So for me, the current work really deals with the closing of one book and the opening of another.

Many, many years ago, a critic said the work was really banal, and I’m like, “Yes, it is. It’s so banal. It’s so about just a regular woman with two kids, living in Brooklyn, and making art and occasionally doing other stuff to-keep-food-on-the-tables-sort-of-thing; and yes, I drive a van and it’s extremely banal. But, you know, that doesn’t mean that we, who are banal, can’t have really truthful and wonderful experiences.” It sounds very corny, but the pieces always feel like children to me in that they have their own personalities and they have their own needs and desires and they have their own abilities. So, once they’re kind of created, I just like shoving them out the door.

Talk Back

Oneself as Another

Is this sculpture a self-portrait of Alison Saar? According to Saar:

“Actually, I think of all my sculptures as self-portraits, although they never look like me. They are all invented figures. But I think that they are self-portraits—even the male figures—in that they all discuss something that I feel emotionally. They are all, in some way, about being left out, about being outsiders."

Does this prevent you from finding something of yourself in Lost and Found, or is this exactly what makes it possible for you—or anybody else—to discover yourself in it?

Quoted in Lisa Lyons, Departures: 11 Artists at the Getty (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000), 49.