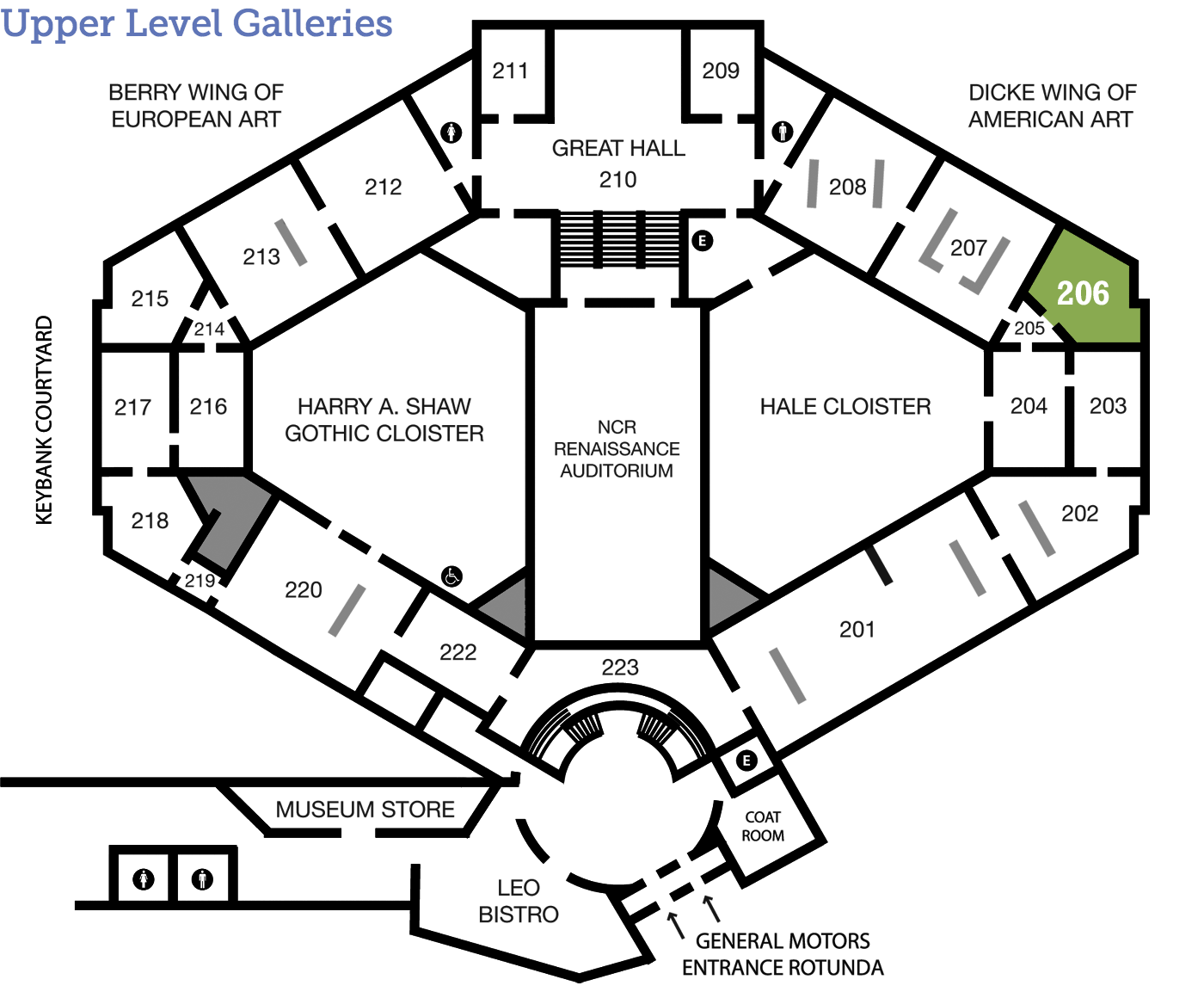

Harriet Frishmuth

Joy of the Waters

(1880-1980)

American 1917 Cast bronze 63 ½ x 15 x 16 inches Gift of Mrs. Harrie G. Carnell 1919.1

Dance for Joy

This sculpture has a lot of reasons to be happy. It holds a unique place in The DAI’s collection, it has received special treatment, and it no longer has to stand out in the rain. Is its joy contagious? Read more to find out.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Becoming Bronze

Can you find little circles on the surface of this sculpture? Look at the inside of the left leg. These are clues that it was made with the lost wax process. This allows an artist to make a very detailed sculpture and to easily produce multiple copies of it. Frishmuth made two versions of this sculpture, one approximately 63 inches the other 44, and there were several castings of both, including those at the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the National Academy Museum and School. Discover the basic process in the following video from the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Lost Wax Bronze Casting from Victoria and Albert Museum on Vimeo.

Behind the Scenes

Preserve and Protect

Look closer at the surface of Joy of the Waters. It did not always look like this. There was significant corrosion and build up of mineral deposits because it was used outside as a fountain for many years (see “Dig Deeper”). Below you can see an image of what it previously looked like.

In 2006, The DAI had the sculpture conserved at the McKay Lodge Conservation Laboratory in Oberlin, Ohio in order to return it to its original appearance. What other repair did it need? What materials and techniques do conservators use to clean and refinish a sculpture? Read all about it in the conservation report submitted to The DAI by Thomas Podnar, Sculpture Conservator at McKay Lodge.

Show report.

Thomas Podnar:

The bronze sculpture, Joy of the Waters, was in poor condition. The sculptor’s fine modeling of the figure was obscured by patterns of black and green streaks of corrosion. Concrete and mineral deposits were bonded to the bronze rocks and leaves at the base of the sculpture. The hands of the sculpture had been damaged in a fall long ago and there were also old holes in the base where the original water system had been attached.

Treatment for Joy of the Waters was designed in a manner which would preserve and protect the sculpture while removing disfiguring corrosion, concrete accretions, and repairing damages. Respecting the current surface texture, which includes original finishing tool marks from the foundry as well as fine corrosion patterns etched into the surface over many years, was of primary importance. This surface texture is a rich historic record of the sculpture from inception at the foundry, through its life out of doors to its current display. A patination color was chosen for the sculpture based on research of the body of Frishmuths’ work, consideration of examples of her works in other collections, treatments to Frishmuth sculptures which we have performed and discussion with [then] museum registrar Charles Carroll.

The surface of the bronze sculpture was cleaned by the JOS method which utilizes a mixture of finely ground glass powder, filtered water and compressed air at low pressures up to 40 pounds per square inch. This cleaning removed soiling and corrosion to a bare bronze surface and exposed all original surface finishing from the foundry including round pins which were fitted to plug holes in the casting when it was made.

As part of the cleaning process, concrete and mineral deposits were loosened and removed with steel tools. Repairs followed. Two holes in the base were closed by TIG (tungsten inert gas) welding with the color matching alloy Phos-bronze-C. Damage to the edge of her hand and loosened pins were chased in the traditional manner with hammers and steel tools and the sculpture was prepared for patination by applying dilute washes of cold potassium sulfide and water solution to the bare surface of the cold bronze.

The prepared bronze sculpture was patinated in the long-established manner of applying chemical solutions of potassium sulfide and ferric nitrate to the bare bronze surface. These solutions of water and chemicals were applied to the surface of the bronze with heat supplied by propane torches.

The patination process consists of alternating applications of dilute chemical solutions applied to the surface with heat and then cooled with copious amounts of cold water. The application and cooling procedure locks the chemically formed color into the pores of the bronze surface. Between applications the sculpture is rubbed with bronze wool and more water to modify and blend the colors which occur during the process. Many applications and rubbings are performed in order to develop the correct look. As the patina develops and the color richens it becomes critical to modify and adjust variations within the patina in order to present an esthetically correct matured look to the sculpture. Once the patina is judged to be esthetically correct it is allowed to sit overnight to age.

The patinated sculpture was coated with a combination of microcrystalline waxes applied to the surface with heat. Wax coatings are the traditional finish for bronze sculptures creating a soft sheen which accentuates the sculptors’ forms and richens the color of the patina. Beeswax was the traditional wax used in the past but its acidity and poor stability have been surpassed by the long chain molecule microcrystalline waxes produced from petroleum.

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Moving Sculpture

Harriet Frishmuth designed Joy of the Waters as a fountain. When it first entered The DAI’s collection in 1919 it was used as an outdoor fountain. Below you can see pictures of it in the garden at The DAI’s original location, a 19th-century mansion on Monument Avenue. At the current building it was a fountain for a time in the Hale Cloister. Later, the sculpture was moved indoors based on conservation needs in order to ensure its availability for future generations.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Number One

Every object in The DAI receives a number when it enters the collection. This is called the acquisition number. If you look at the label for Joy of the Waters, you can see its number: “1919.1.” This means it was the first object acquired by The DAI in 1919, the year the museum was incorporated, making it the first object in The DAI’s collection.

Expert Opinion

Look Around

About the Artist

Sculptor of Movement

Harriet Frishmuth was very interested in capturing movement in her sculptures, and the model she used for most of them was a dancer, Desha Delteil (1899–1980). She made two versions of Joy of the Waters, the first a larger one with a model named Janette Ransome, and a second smaller one with Delteil. The DAI’s is the larger version; you can see an example of the smaller version here.

Born in Philadelphia in 1880, Frishmuth spent much of her youth in Europe. Like many sculptors at the time, she was strongly influenced by the work of the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). The naturalism and movement of his works inspired many artists to break from the ideal, classical tradition. In particular, Frishmuth credited him with teaching her two things:

First, always look at the silhouette of a subject and be guided by it; second, remember that movement is the transition from one attitude to another. It is a bit of what was and a bit of what is to be.

Quoted in “Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, American Sculptor,” Courier (Syracuse University Library Associates), 9/1 (October 1971), 22.

Compare Joy of the Waters to a sculpture by Rodin of the famous ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky (1890–1950) below, and consider why a dancer would make an effective model for a sculptor.

Talk Back

Here or There?

Joy of the Waters was originally designed as a garden fountain and was used like this for many years. Now it is inside, surrounded by other American paintings from the same time period. How would your experience of the sculpture change if you saw it as a fountain in a garden (see “Dig Deeper”)? What benefits are there from viewing it in a gallery?