Vanuatuan (Melanesian)

Double-faced Headdress Mask for Nalawan Ritual

Feathers, pigment, tusks, teeth, fiber, vegetable fiber, clay encrustation Height (without feathers): 13 inches (33 cm) Gift of Dr. Arthur M. Culler 1944.84

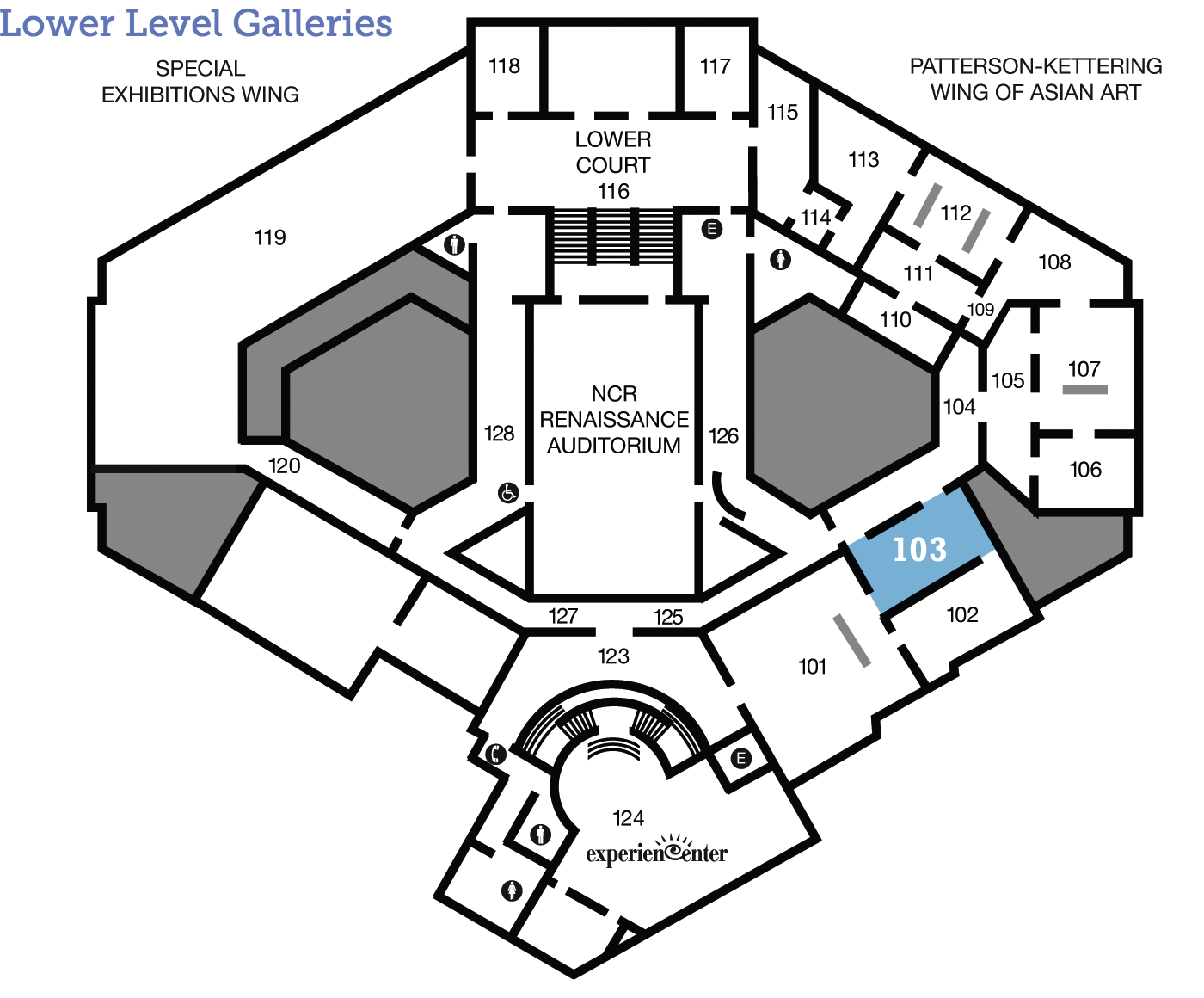

Face to Face

Do you ever wear masks? What is the occasion? What do they say about who you are? Learn more about what masks may reveal—and conceal—with this two-sided headdress mask from the islands of Vanuatu.

A Day in the Life

A Voyage to Vanuatu

This headdress mask comes from Malakula (mah-lah-ku-lah), the second largest island in Vanuatu (vah-nu-ah-tu), a nation of 85 islands in the southwestern Pacific Ocean near Australia. Malakula has about 28,000 people, with 35 different languages and 50–80 different dialects. About 10,000 people live in the southern half of the island, speaking 19 languages. This two-sided mask is from the Nahava (nah-hah-vah)-speaking peoples in the Sinesip (see-neh-seep) area in southwest Malakula. (Note that most of the languages in Vanuatu are not written, so this is one possible way of writing names with a Roman alphabet.)

Quiz

Overall, Vanuatu is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse regions on earth. As of 2011, guess how many indigenous languages were spoken in Vanuatu?

110

95

75

60

Further reading: Kirk Huffman, “‘Noho’n’dou Yene Nieve Nungute’i Numuwo’h Yene—Respect is the Foundation of Life’: Rituals, Respect, Ancestors, Spirits, ‘Art’ and Kastom in Vanuatu,” in Kastom: Art of Vanuatu, Crispin Howarth (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2013), 30–35.

Tools and Techniques

Piggy Bank

Look closer at the mouth and eyebrows on this headdress mask. These are pigs’ tusks. Pigs are the most important animal in Vanuatu, essential to social, economic, and ritual life. In the northern Vanuatu islands the curvature of the tusk is what determines the value; live pigs can be used as currency and even lent out at rates of interest. Valuing the tusks on the live animal contrasts with the ivory trade, which values only the material apart from the animal.

An extraordinary amount of energy goes into cultivating premium tusks. Knocking out the upper incisor in a young male pig permits the lower tusk to grow in a curve and, after about five or six years, a full circle; a double circle, even more valuable, takes about twice as long.

Membership entry into Nalawan (see “Dig Deeper”), and one’s rights to ritual knowledge and paraphernalia (like this mask) depend upon sponsorship and payment in the form of male tusker pigs. The pigs’ tusks on this mask indicate not only its spiritual power—some northern Vanuatu cultures consider the pigs to have souls that may benefit humans—but also its value.

Further reading: Kirk Huffman, “Pigs, Prestige and Copyright in the Western Pacific,” Explore: The Australian Museum Magazine 29/6 (2008): 22–25.

(photograph by and courtesy of Stan Combs)

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

Little is known about this two-faced mask. Only those who belong to a secret club in Vanuatu know the true meaning. What do you think the mask is used for? Why do you think it has two faces?

Without all the facts it can be frustrating or hard to understand this mask. Think of it as a visual Mad Libs. It is missing the important elements that tell us who wears the mask and why they wear it.

Signs & Symbols

Classified Information

For years The DAI called this a Janus Mask after the Roman god Janus, the god of doors and beginnings, who was depicted as having two faces. It is also sometimes used as a general label for any mask that has two faces. However, this can be misleading as it may import ideas associated with Janus that are not relevant for this or any other mask from a different cultural context.

So, what is the name of this headdress mask, what spirit form does it represent, and why does it have two faces? Such information is, in a sense, part of its copyrighted content. Only those with membership in the Nalawan society that use it have a right to access this content (see “Dig Deeper”). In a time of perceived all-access information through media, we may insist on a right to know. However, even in “modern” societies such as ours there is restricted information, although it is usually governments and corporations that control this. What is the value of protecting and respecting such claims that an outside audience should not know everything about this headdress mask? Consider how not knowing certain information affects the way you engage with it.

Dig Deeper

A Living Tradition

Headdress masks like this are worn in Nalawan (nah-lah-wahn) rituals. Nalawan is the general term for a myriad of male-only restricted-entry societies that maintain specific—and in a sense copyrighted—ritual knowledge and performance. These societies continue today. The mask is a materialized spirit form that permits the wearer, during the ritual, to become the spirit that it portrays.

Nalawan are one piece of the larger puzzle of Kastom (kah-stohm), the pidgin word for the traditional way of life in the islands in Vanuatu—including beliefs and rituals—that has been practiced for untold generations. It is a way of understanding and cultivating the connections between the human material world and the non-material spirit worlds.

All major participants in Nalawan are male, but female relatives may play a minor supporting role in ritual dance processions. Likewise, women have their own rituals and dance processions where men are excluded, or play a minor role.

Further reading: Kirk Huffman, “‘Noho’n’dou Yene Nieve Nungute’i Numuwo’h Yene—Respect is the Foundation of Life’: Rituals, Respect, Ancestors, Spirits, ‘Art’ and Kastom in Vanuatu,” in Kastom: Art of Vanuatu, Crispin Howarth (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2013), 30–35.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

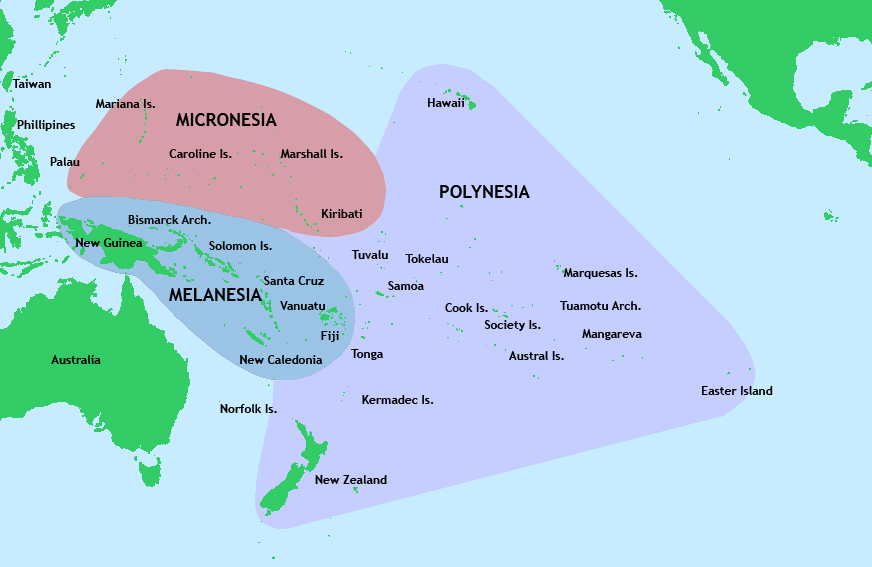

Where is Oceania?

This headdress mask is called a work of Oceanic art, which refers to art that comes from the region of Oceania. The 30,000 islands of Oceania are divided into sub regions of common languages: Melanesia (“black islands”), Polynesia (“many islands”), and Micronesia (“small islands”). This mask originates from Vanuatu, a country of about 85 islands within the Melanesian island group (see “A Day in the Life”).

(public domain; photograph provided by Wikimedia Commons)

Expert Opinion

Look Around

About the Artist

Talk Back

Face On or Off?

This headdress mask permits the wearer, during a Nalawan ritual, to become the spirit that it portrays. In different times and places people have worn masks as a means to become somebody, or something, else. What is it about a mask that empowers people to be different than they are without a mask? What are the kinds of “masks” people may use today to experience being somebody else, or to present an ideal self to others?