Chinese

Ritual Wine Vessel (Jue)

Chinese Bronze Height: 8 3/8 inches Gift of Mrs. Virginia Kettering 1950.24

Put the Kettle On

How many of your best conversations with friends or family have happened over a drink? A cup of tea or coffee, a cold soda, or a glass of wine? Conversations also happened around this ancient bronze vessel from China, although perhaps not quite like you think.

A Day in the Life

The Chinese Bronze Age

We do not know exactly when bronze technology started in China, but it was well-developed by the time of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BCE), the earliest Chinese dynasty with an archaeological record. Bronze literally strengthened the social structure, as it was used to make weapons, ritual vessels, and parts for chariots.

This jue was made with a piece-mold casting process, a technique unique to China at the time. There were many steps:

1. A model of the desired object was made with clay.

2. An additional layer of clay was put over the model; once dry, it was cut in sections, removed, and fired, creating pieces for a mold.

3. The clay model was trimmed down until it formed the core of the vessel, which would create a concave space during casting.

4. The pieces of the mold were assembled around the core and molten bronze was poured in the space between.

5. After cooling, the outer mold was broken away and any unwanted bits were cleaned off. Since the mold was destroyed in the process, each cast piece was one-of-a-kind.

This way of bronze casting has similarities with the technique of lost-wax casting that was practiced in other regions. To watch a video on this process click here.

Further reading: Department of Asian Art, "Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China“, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/shzh/hd_shzh.htm (October 2004).

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Better with Age

According to Michael Flanigan, an appraiser for the popular TV program Antiques Roadshow, "Patina is everything that happens to an object over the course of time. The nick in the leg of a table, a scratch on a table top, the loss of moisture in the paint, the crackling of a finish or a glaze in ceramics, the gentle wear patterns on the edge of a plate. Patina is built from all the effects, natural and man-made, that create a true antique."

Though some artists carefully and intentionally apply a patina to their works to give them a more finished or decorative appearance, the patina on this ancient bronze vessel is the result of thousands of years of contact with dirt and other elements that have gradually caused a chemical change on its surface.

Poll

Looking at the patina here as a part of a work of art, do you prefer to see the evidence that this piece is thousands of years old, or would you rather see it as it was when it was freshly cast?

To see the rest of Michael Flanigan’s comments on patina click here.

Look Closer

Are those mushrooms sprouting on top of that?

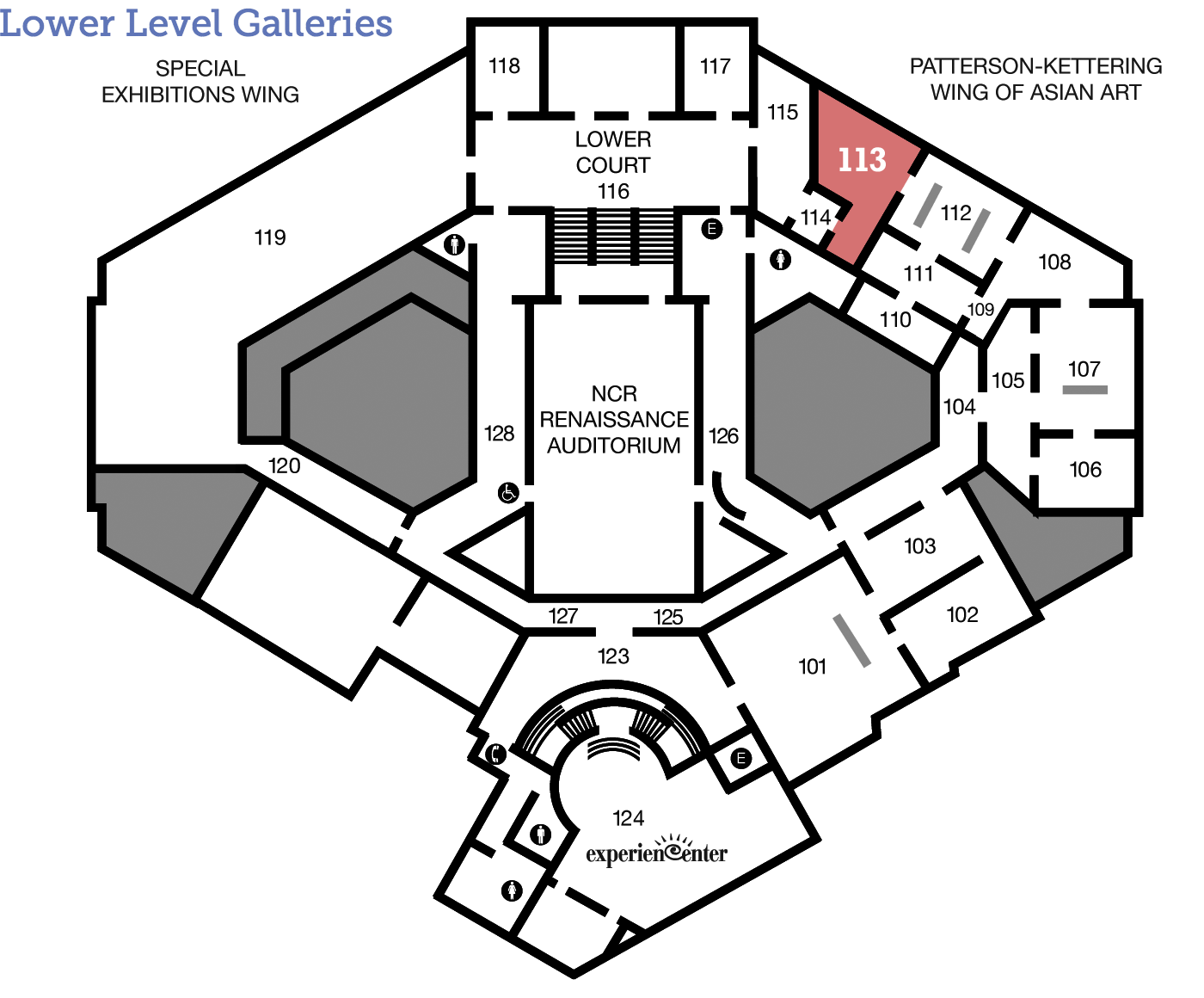

This jue was used in special rituals directed towards one’s ancestors. The long, wide legs made it easy to heat black millet wine by placing the jue directly over coals. A jue was often paired with a gu, a slender drinking cup, and sometimes a jia, a larger, three-legged pot also for heating wine. Examples of these in The DAI’s collection are nearby.

Quiz

Form follows function in this carefully balanced ritual vessel. Can you guess what the mushroom-like posts on top of the vessel are for?

Resting a spoon or ladle.

Added decoration to make it look like a duck.

Lifting the vessel from the fire and pouring.

Supporting the casting process.

Further reading: Elizabeth Childs-Johnson, “The Jue and Its Ceremonial Use in the Ancestor Cult of China," Artibus Asiae 48/3–4 (1987), pp. 171–196.

Just for Kids

Look!

This vessel is used to heat wine during special celebrations and rituals to receive advice and blessings. Look at the Korean Tea Bowl. This vessel was used for drinking tea. These vessels have many opposite characteristics—can you list some others? Tell them to a friend or family member.

Look around the museum and make a list of all the opposites you notice.

Signs & Symbols

Face to Face

Look closer at the decoration around the middle of the jue. Can you see a face on either side? This is a common decoration on bronze vessels from the Shang dynasty period. Known as a taotie, it is a symmetrical, mask-like design whose exact meaning is unknown. The features vary from vessel to vessel, but it usually consists of two bulging eyes, a strong brow or horns, and a kind of fang or beak-like upper jaw. The motif appears on the other Shang-era objects nearby. Can you find them?

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

A Family Ritual

Vessels like this jue were used by leaders in special rituals to get advice, blessings, and protection from deceased ancestors. We can catch a glimpse of a similar ceremony in the Book of Songs (Shi jing), the oldest collection of poems in Chinese literature, with some dating to the Zhou dynasty (1050–256 BCE), which came after the Shang dynasty.

The musicians go in and play,

That after-blessings may be secured.

The [meats] are passed round;

No one is discontented, all are happy;

They are drunk, they are sated.

Small and great all bow their heads:

“The Spirits,” they say, “enjoyed their drink and food

And will give our lord a long life.

He will be very favored and blessed,

And because nothing was left undone,

By son’s sons and grandson’s grandsons

Shall his line for ever be continued.

Quote from The Book of Songs, translated by Arthur Waley (New York: Grove Press, 1960), 211.

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

About the Artist

Talk Back

One-of-a-kind

Since this vessel was cast with the piece-mold process, the clay mold was destroyed each time (see "A Day in the Life"). This meant each bronze piece was completely unique. How does the uniqueness of a work of art affect how you see it and evaluate it? Does a work of art have to be one-of-a-kind to be a masterpiece?