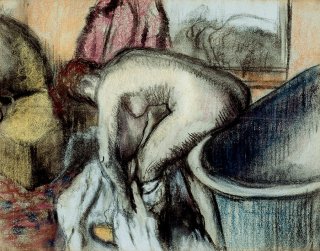

Edgar Degas

After the Bath

(1834–1917)

French 1895 Pastel on paper 18 x 23 ¼ inches Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Haswell 1952.33

Invasion of Privacy?

An unknown woman performs the mundane task of drying herself after bathing. Is she unaware of the viewer over her shoulder? Does this place us in the position of a spy? Degas’ late pastel drawings of solitary women in private moments like this opened new visual horizons.

A Day in the Life

Bath Time

Degas produced many drawings and etchings of women taking baths. What do these say about views of personal hygiene in France at the time? Find out more in the following video from the Clark Art Institute about the etching Leaving the Bath. And after seeing the etching, look back at The DAI’s pastel drawing and consider how the two mediums present this subject in different ways.

Transcript:

Degas’ tiny but technically innovative print Leaving the Bath was drawn and redrawn, printed and reprinted, in at least 22 different states during 1879 and 1880. Numerous impressions were auctioned in the sale of the artist's prints in 1918 and the image was published in the complete catalogue of his work the following year. The figure in Degas' print is shown in a slightly ungainly pose, one leg in, one leg out of the bathtub as she steps into the folds of a towel held up by her maid.

The steady rise in the number of Degas' toilette and quaferre scenes from the mid 1870s onward coincides with an increasing French obsession with personal hygiene. Although all the experts agree that regular washing with soap and water was essential, there was considerable disagreement about the frequency with which one ought to immerse oneself in water as opposed to having a simple sponge bath in a basin. Degas depicted all the forms of bathing equipment in use in his day, from the most basic portable tub to the coveted, but rare, fully plumbed in bath, and his studio was equipped with all the necessary props.

© Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

Tools and Techniques

A Light Touch

Do you see a secret message somewhere in the bathtub? Actually this is the watermark of the manufacturer of the paper, P.L. Bas. Degas worked with a variety of papers throughout his career. After the Bath is on laid paper, on which its mold leaves small lines across the surface. These lines create a semi-rough texture that allows particles of paper to remain visible beneath the pastels, depending on how heavily they are applied. Degas used this to unique effects, such as evoking the play of light on objects. In After the Bath the pastels are applied lightly enough that the watermark still shows through.

Degas worked with many artistic media, including paint, print, and wax sculpture, but pastel was the medium he used the most. Pastels are made with crushed color pigments mixed with a base—such as white chalk—and a binder that holds them together. Changing the proportions of each material can produce a variety of colors, shades, and degrees of hardness. Pastels have many benefits: they require little preparation and drying, allow an artist to make easy alterations, and are quite stable over time.

Further reading: Anne F. Maheux, “Looking into Degas’s Pastel Technique,” in Degas Pastels, Jean Sutherland Boggs and Anne Maheux (New York: George Braziller, 1992), 19–38.

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Degas and Women

Women are the subject of many of Degas’ artworks, from ballerinas to bathers, and viewers often have different reactions to them. Dig deeper into this issue in the following video from the J. Paul Getty Museum that discusses the painting After the Bath (1895). Compare this with how the woman is portrayed in The DAI’s After the Bath, and then express your own opinion in the poll below.

© J. Paul Getty Museum

Transcript:

Narrator: A woman dries off after a bath in this intimate painting by Edgar Degas. There’s nothing ideal about the way the artist has depicted her body. Her position is awkward and unflattering. Her long red hair is a disheveled blur of paint. Charlotte Eyerman, Assistant Curator of Paintings at the Getty:

Charlotte Eyerman: Why is her leg up on the bath tub? Why is her arm akimbo like that? It’s important to remember when we’re looking at a Degas that Degas was trained according to the most traditional, most conservative, most conventional ways of painting, and that is the Academic system. He’s very intentionally making a painting that is hard to read spatially, that is challenging in its composition, that treats the female body in a way that is interested more in abstraction and disjunction than a kind of traditional celebration of the female nude body as sensual or canonically attractive.

Narrator: As Degas himself reportedly once said, “Women can never forgive me; they hate me. They feel that I am disarming them. I show them without their coquetry.” Today, critics and viewers alike struggle to come to terms with some of Degas’ representations of women. Are they intentionally cruel, or simply unflattering, [or naturalistic, like a spontaneous snapshot]?

Poll

How would you describe Degas' depictions of women?

Arts Intersected

Seeing through the Keyhole

What might it look like if the bather in Degas’ drawing came to life? See one possibility in the following dance called "The Keyhole," choreographed by Christie Zimmerman, Associate Professor of Dance at Ball State University, and performed by Cristina Gustaitis. Speaking about the background for the dance, Christie Zimmerman said:

The Keyhole was inspired by a series of bathers painted by Edgar Degas in the late 1800’s. Many critics have stated that the figures portrayed in the drawings seem natural and uninhibited, candid and spontaneous, almost as if they are unaware of the presence of the painter. Degas himself, when speaking of the bather series, is quoted as saying, "I want to look through the keyhole."

For Degas quote see: Robert Hughes, “Degas,” in Nothing if Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists (New York: Penguin, 1990), 92–96.

the keyhole from Christie Zimmerman on Vimeo.

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

About the Artist

Talk Back

Beyond Impressionism?

Art writers have debated whether to call Degas a Realist or an Impressionist. “Realist” refers to artists in the 1800s who focused on depicting daily life in a direct and non-ideal way. “Impressionist” refers to a group of painters in France in the late 1800s who used vivid colors and short, unblended brushstrokes to try to convey the atmospheric effects of light and the vibrancy of modern life. They held their own exhibitions in the 1870s and 1880s, since most had been rejected by the official annual art competition known as the Salon. Many of Degas’ most famous works, such as The Dance Class, come from this period.

However, after the last Impressionist exhibition in 1886 Degas entered an intensely creative phase. Over the next 25 years he experimented with materials—especially pastels and wax sculpture—and narrowed his subject matter, focusing on the simplicity of the human figure, as in After the Bath. The result is innovative images that show Degas was aware of trends in art that continued after Impressionism, and he was not content to settle in a particular category.

Would you consider Degas’ style to be Realist or Impressionist? Would you use another word? How do labels like these help—or hinder—how you understand Degas’ art?