Radical

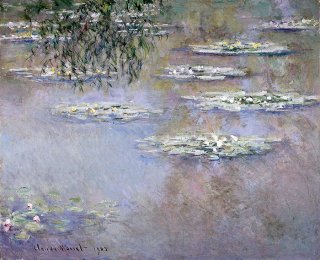

Does this painting make you feel calm? The changes in culture and technology that led to its creation were radical. The advent of trains and paint in portable tubes allowed painters like Claude Monet to work outside as never before, helping them challenge the establishment art of the time, and changing the face of painting forever.

A Day in the Life

Monet, LIVE!

You have seen the painting, now see the artist! Watch Monet in action, painting another waterlilies scene in his garden in Giverny. The clip is from the 1915 documentary Those of Our Land (Ceux de chez nous) by the filmmaker Sacha Guitry. It contained short films of French artists of the time, including Renoir, Degas, and Rodin. As you watch Monet apply paint to the canvas, can you see traces of similar movements in The DAI’s version of waterlilies?

Tools and Techniques

Monet’s Colors

When you stand back and look at this painting the colors give the impression of waterlilies on a pond. But what would the colors look like if you put them under a microscope? Take a closer look at the different color pigments Monet used in his paintings here, in an interactive slideshow from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. As you look at the colors, see if you can find them being used somewhere in The DAI’s version of waterlilies.

Behind the Scenes

A Random Act of Kindness

Museums acquire artworks in many ways, sometimes very surprising ones! Find out about the unexpected way The DAI received this Monet painting in the following story from Alex Nyerges, Director and CEO of The DAI from 1992–2006.

This work was given to the Art Institute by a gentleman by the name of Mr. Joseph Rubin, who ran a company in New York City called the Loma Dress Corporation. And sometime before 1953, Dr. Esther Seaver, who was the Director of The Dayton Art Institute in the first part of the 1950s, had encountered this picture and was acquainted with a dealer in New York by the name of Silberman and began a correspondence with Silberman and then Rubin, to say that, “I know I’m taking liberty of requesting the painting for The Dayton Art Institute in the event that you would consider giving it to a museum outside the New York area.” He wrote back that he would be pleased to give it to the collection of the Art Institute: “This museum has made steady progress since 1919. I would like to help such an institution. I feel therefore that I wish to present a fine painting to a museum outside of New York, where art facilities are more limited than here. I think this would be a greater civic service.” And of course today, nearly 50 years later, we can thank Mr. Rubin for his generosity in improving the lot of an institution and a community like Dayton, Ohio.

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

Do you like to explore your backyard? Claude Monet did! He was even inspired to paint from his garden and pond at his house in Giverny, France. He often painted the same scenes at different times of the day and during different seasons. Why do you think he painted the same scene at different times of the day and year?

Look at the painting again. This time observe the habitat that Monet created. What kind of habitat is it? What types of plants and animals might live there? What kinds of sounds might you hear if you visited Monet’s house? What would his backyard smell like?

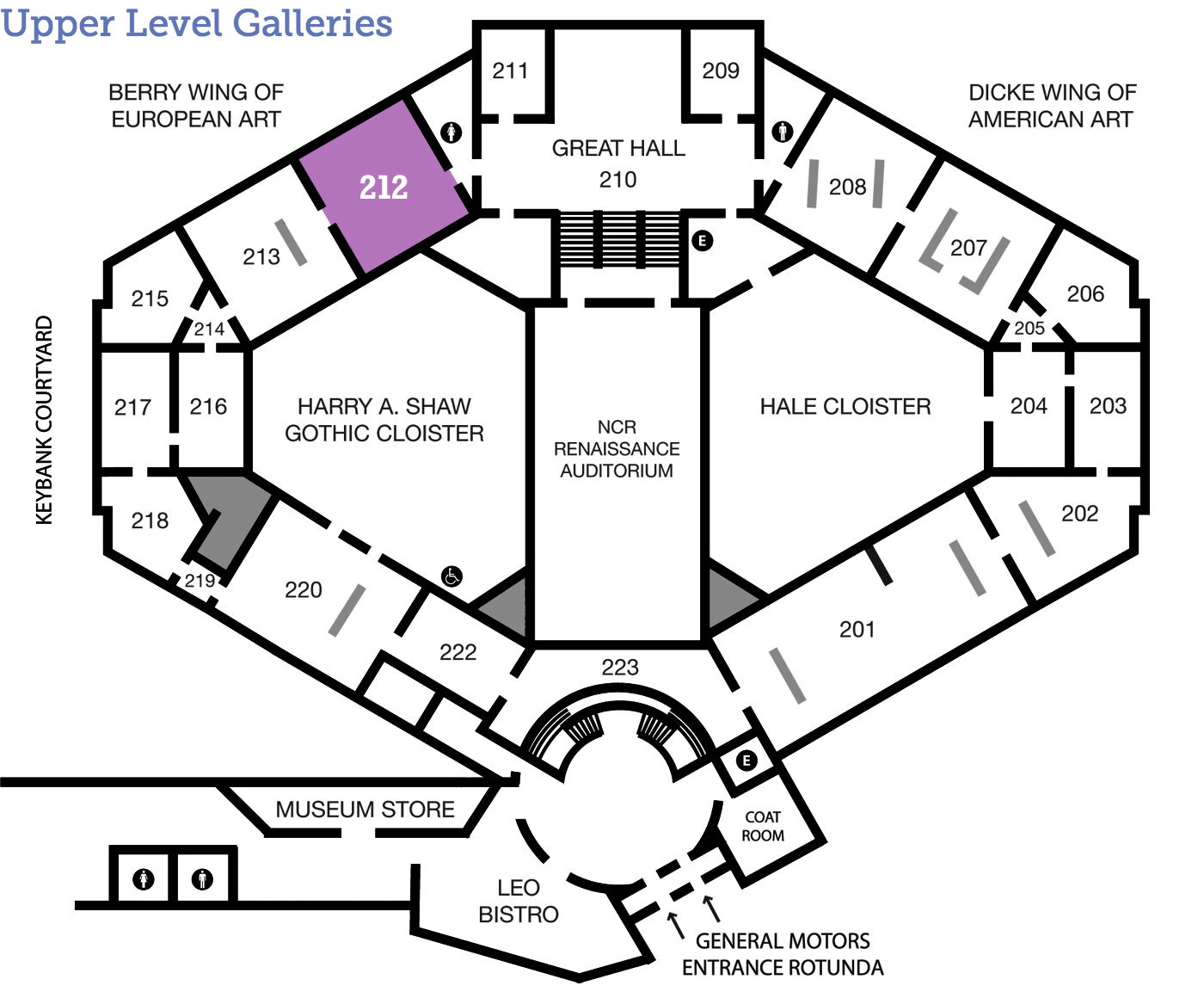

Look around at the other paintings in this gallery. What kind of habitats have been created? Are they the same as or different than Monet’s? What kinds of animals might live in these habitats?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Monet’s Legacy

Throughout his career Monet did many series of works, capturing the same subject at different times or locations. His largest and most famous series is of water lilies from his home in Giverny, and The DAI’s painting is an early example from this group. As Monet focused on painting what he immediately perceived, he simplified shapes in favor of color and created atmospheric effects with loose, gestural brushstrokes. The combined result challenges how we perceive surface and depth in a painting.

Modern abstract painters in the 1900s would take Monet’s innovations further. For example, look at Joan Mitchell’s Untitled in Gallery 201. Mitchell was very interested in nature, but rather than depict it she translated her experience into an abstract combination of colors applied with animated brushstrokes. Does this lack of a recognizable object change how you interact with the painting? Does the painting evoke any sensations of nature, such as the feel of wind or the smell of grass? As you explore the modern galleries, look for echoes of Monet in other paintings.

Joan Mitchell (American, 1925–1992), Untitled, c.1961, oil on canvas, 76 ½ x 51 inches. Gift of Mr. Max Pincus in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Elton F. MacDonald, 1964.25.

About the Artist

Talk Back

What is Your Impression?

Monet attempted to paint as the eye saw, capturing the play of light and the blending of colors that are constantly changing in the environment. If you were looking over Monet’s shoulder at the real waterlilies he painted here, would they have appeared as “beautiful” to you? What is the alternative experience that you get from the painting that you might not get from seeing the waterlilies yourself, or seeing them in a photograph?