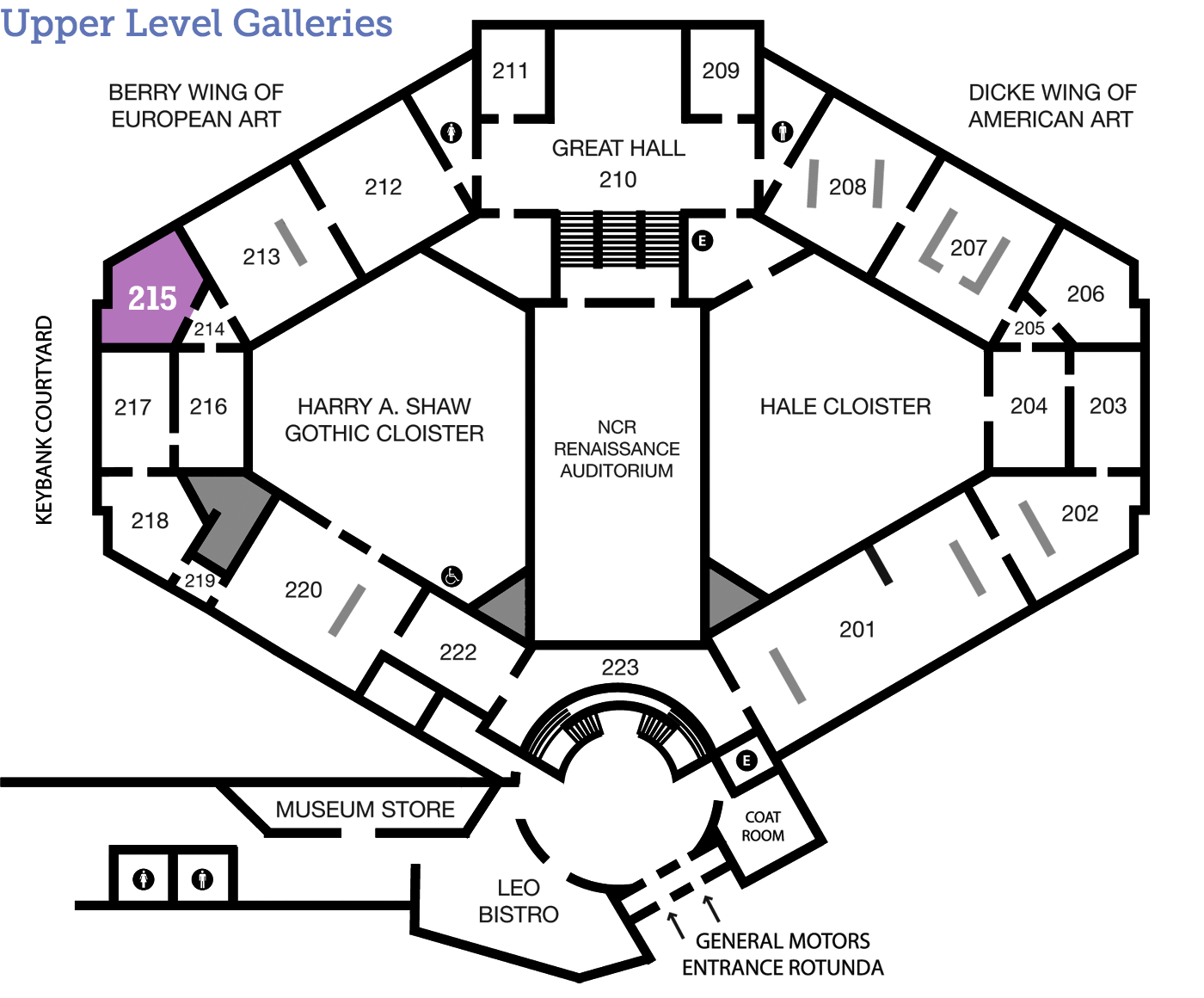

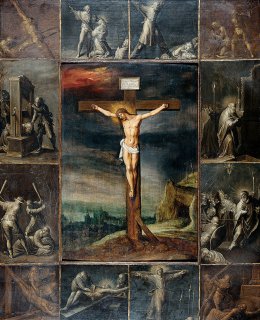

Frans Francken the Younger

The Crucified Christ Enframed with Scenes of Martyrdom of the Apostles

(1581–1642)

Flemish c. 1630 Oil on wood 34 ½ x 27 ¾ inches Gift of Mr. Robert Badenhop 1954.15 215

Visual Literacy

What can art teach you about faith, either your own or somebody else’s? Look closer at this panel painting and discover why its educational function was so imperative three hundred years ago, and how it still makes an impression on viewers today.

A Day in the Life

Worth A Thousand Words

During the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation brought religious, political, cultural, and intellectual upheaval that splintered Catholic Europe and left its mark on the religious art of the region. Protestantism flourished for a brief time in Antwerp. As elsewhere in the Netherlands, rioting members of the movement destroyed many of the city’s religious paintings and sculptures, which they perceived as “false idols” put in place by the corrupt Catholic Church.

However, a Catholic resurgence known as the Counter Reformation arose in response to the Protestant outbursts, and in 1563 the Council of Trent decreed that art was a critical educational tool in the Catholic faith. The fact that much of the public was illiterate and could not read the Bible supported such claims. By 1567, Antwerp’s Council of Troubles began to persecute practitioners of Protestantism; soon after the city was flooded with religious art, and citizens took to collecting art as a means of demonstrating their piety. This painting would have hung in an individual’s home for private devotion, its graphic scenes detailing the various sacrifices that Christ and his apostles made for mankind and Christianity.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Sacred Deaths

Each scene within this painting provides an opportunity to learn about Christ and his followers. The paintings around the colored center panel are done in grisaille, a monochrome painting technique that uses only shades of grey or another neutral color.

During the 17th century, there were numerous printed sources available to Antwerp citizens that provided information on the saints. The most well-known of these was The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, a 13th-century text which we have used, along with similar books, to identify the figures in this painting. Tap on the scenes that interest you to find out more.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Collaboration and Competition

Many other well-known artists were working in Antwerp in the 17th century, and they often collaborated. Artists like Jan Bruegel the Elder often enlisted Peter Paul Rubens’ help with figure painting and represented Rubens’ works in his kunstkammer paintings. Francken, perhaps so as not to assist the competition, only did so on rare occasions.

Notably, Study Heads of an Old Man by Peter Paul Rubens hangs in the same gallery as this panel panting. Take a moment to compare the formal qualities of the two works, including their scale and brushwork.

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1641), Study of Heads of an Old Man, c. 1612, oil on oak panel, 26 ½ x 19 ¾ inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carlton W. Smith, 1960.82.

About the Artist

Paintings within a Painting

The Francken family were well known in Antwerp as skilled artists, however Frans Francken the Younger left the greatest mark on the city; he was the first creator of a kunstkammer painting—a representation, sometimes idealized, of a wealthy citizen's art collection. Today there are about one hundred of these popular works by a variety of artists, and through examining the paintings within these paintings, art historians have been able to reconstruct the art collecting trends of the past. Tap on the hotspots below to see which works Francken replicated—and other details—in this 1630 kunstkammer, titled Banquet at the House of Burgomaster Nicolas Rockox.

Frans Francken the Younger (Flemish, 1581–1642), Banquet in the House of Burgomaster Nicolas Rockox, c. 1630–1635, oil on oak, 24.5 x 38 inches. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Inv. 868 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by bpk, Berlin/Alte Pinakothek/Art Resource, NY).

Talk Back

Touching Art

In some branches of the Christian tradition, images of the saints are often venerated through touch, connecting the believer and the object of faith in an intimate way. When these objects are in a museum, this veneration takes a different form by necessity. Museum curators might display such objects for reasons besides their devotional value, such as the skill of the artist, the age of the work, or what it may teach us about the time when it was made. And since the museum’s mission is to preserve and protect art for the enjoyment of our visitors today and for future generations, touching is prohibited because our hands contain harmful oils that corrode and discolor the surface of paintings, changing how they look and lessening their life expectancy.

Take a look at the wall labels and the other artwork hanging in Gallery 215. Does the placement of this painting in a museum as compared to a private individual’s home transform its meaning in any way? How? For what reasons do you find this object important?