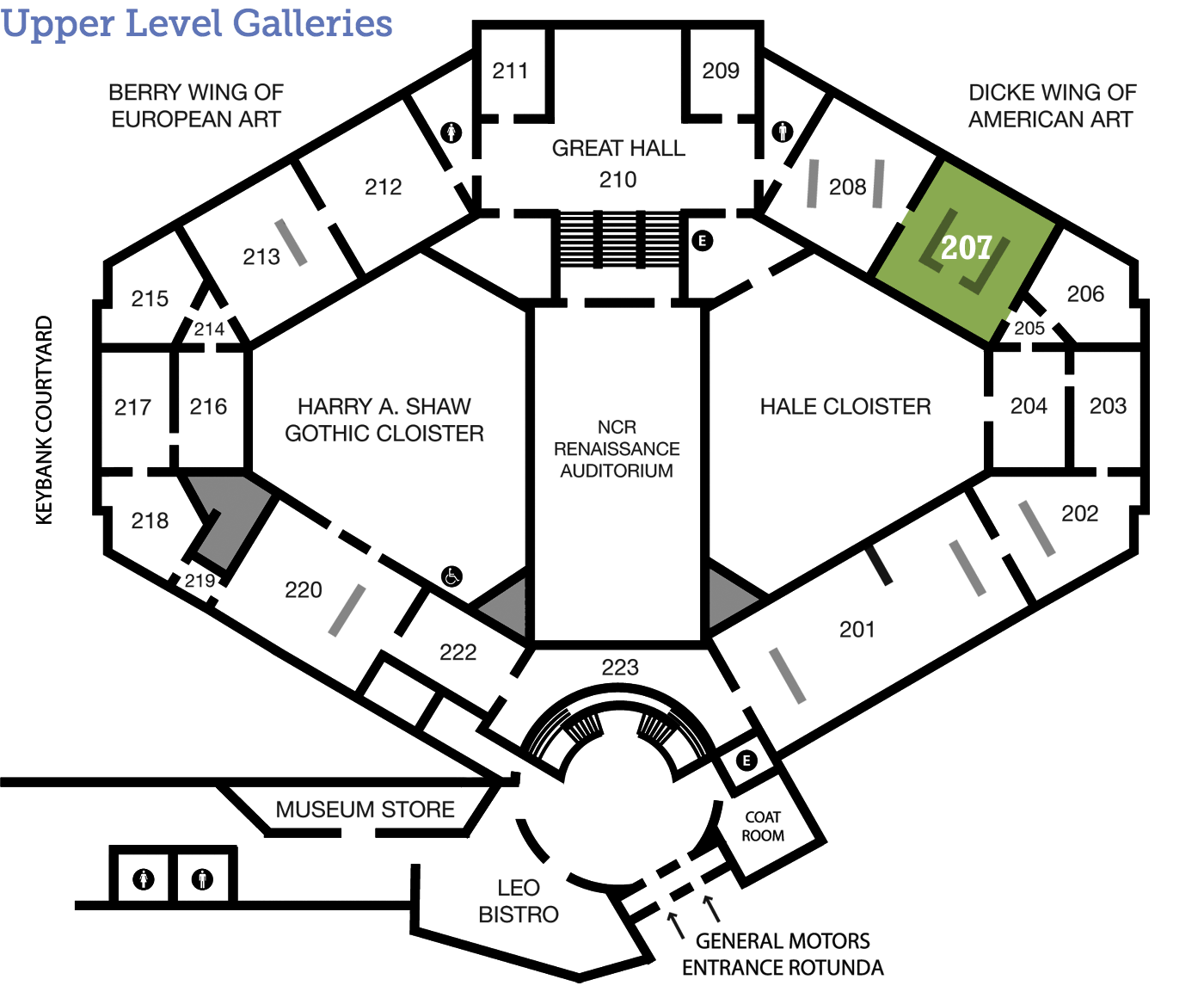

Junius Brutus Stearns

Washington on His Deathbed

(1810-1885)

American 1851 oil on canvas 37¼ x 54⅛ in. Gift of Mr. Richard Badenhop 1954.16

The Legends of Washington’s Death

How did it happen? The 19th century was rife with paintings imagining the death of George Washington. Some artists portrayed the event with baroque drama and splendor, while others convey a more earthly presence and stoic passing. First-hand accounts inspired this narrative painting; artistic liberty embellished it. Explore the tabs below for other visual interpretations of the death of our nation’s first president.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Copy That

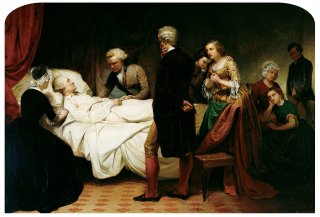

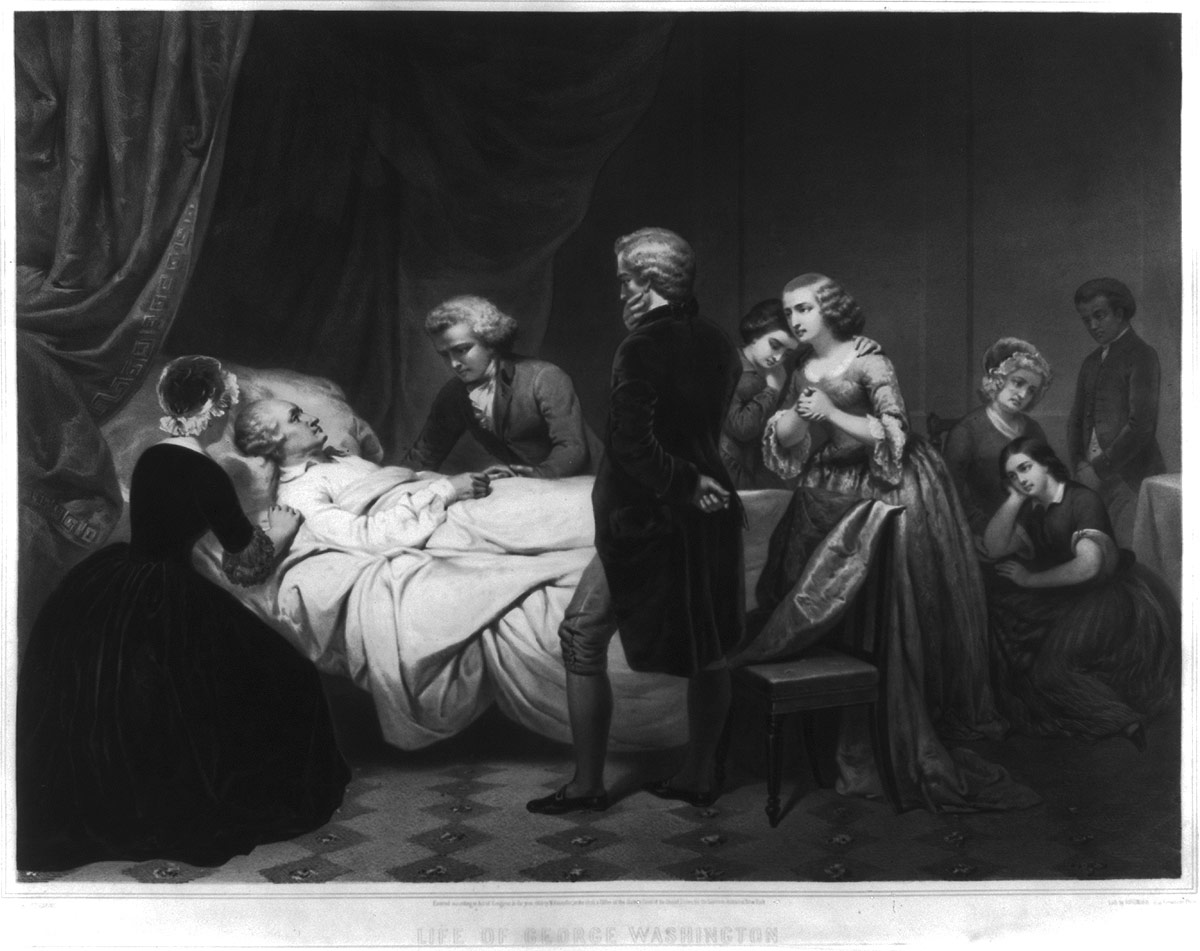

Lithography was commonly used in the 19th century as a quick and inexpensive means of reproducing texts and images. Lithographers frequently made prints of popular paintings in order to increase the work’s visibility. Below are some examples of lithographs depicting the scene of Washington’s death.

Junius Brutus Stearns (lithograph by Régnier, imprint by Lemercier), Life of George Washington The Christian Death, c. 1853, lithograph, hand-colored.

This image is easily identifiable as Stearns’s Washington on His Deathbed, but it was distributed under the title The Christian Death to promote the idea that Washington was religious.

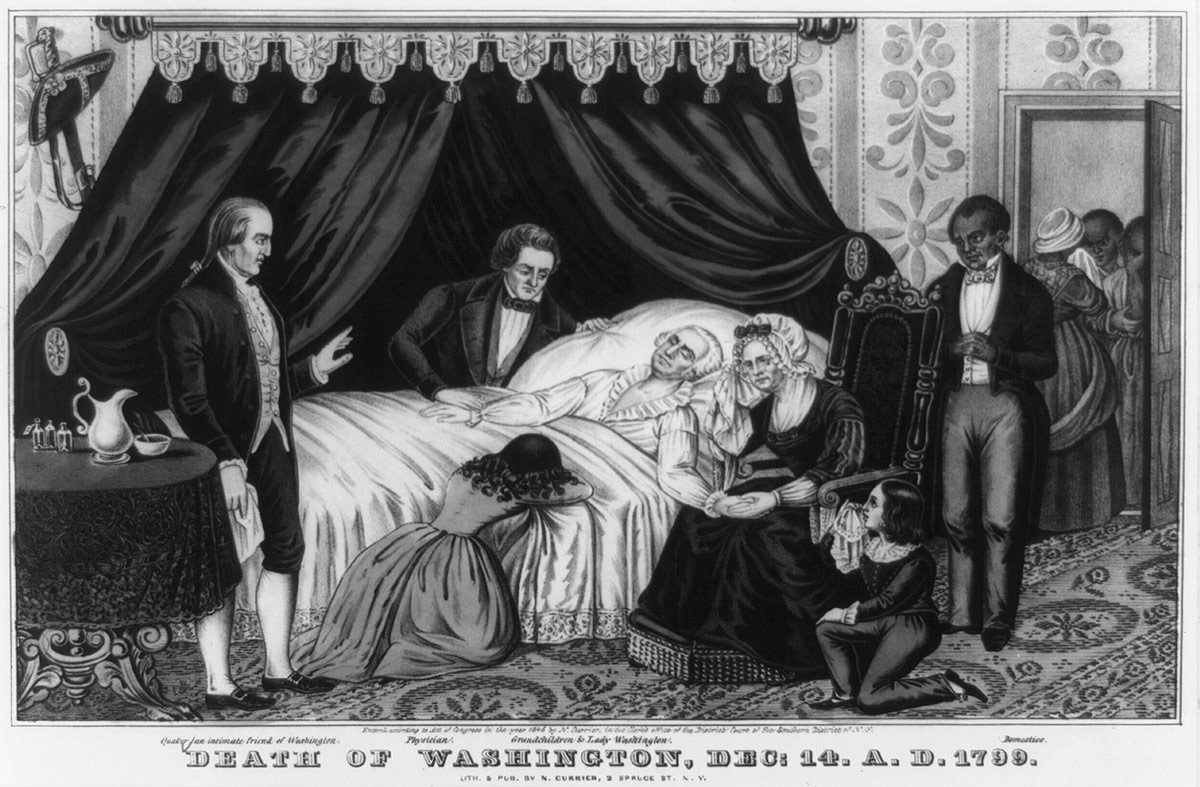

N. Currier (Firm), Death of Washington, Dec: 14. A.D. 1799, 1846, lithograph, hand-colored.

This lithograph by the print firm Currier (of Currier and Ives) is known to have been produced in 1846—before Stearns made his painting. Do you think it influenced Stearns’s composition?

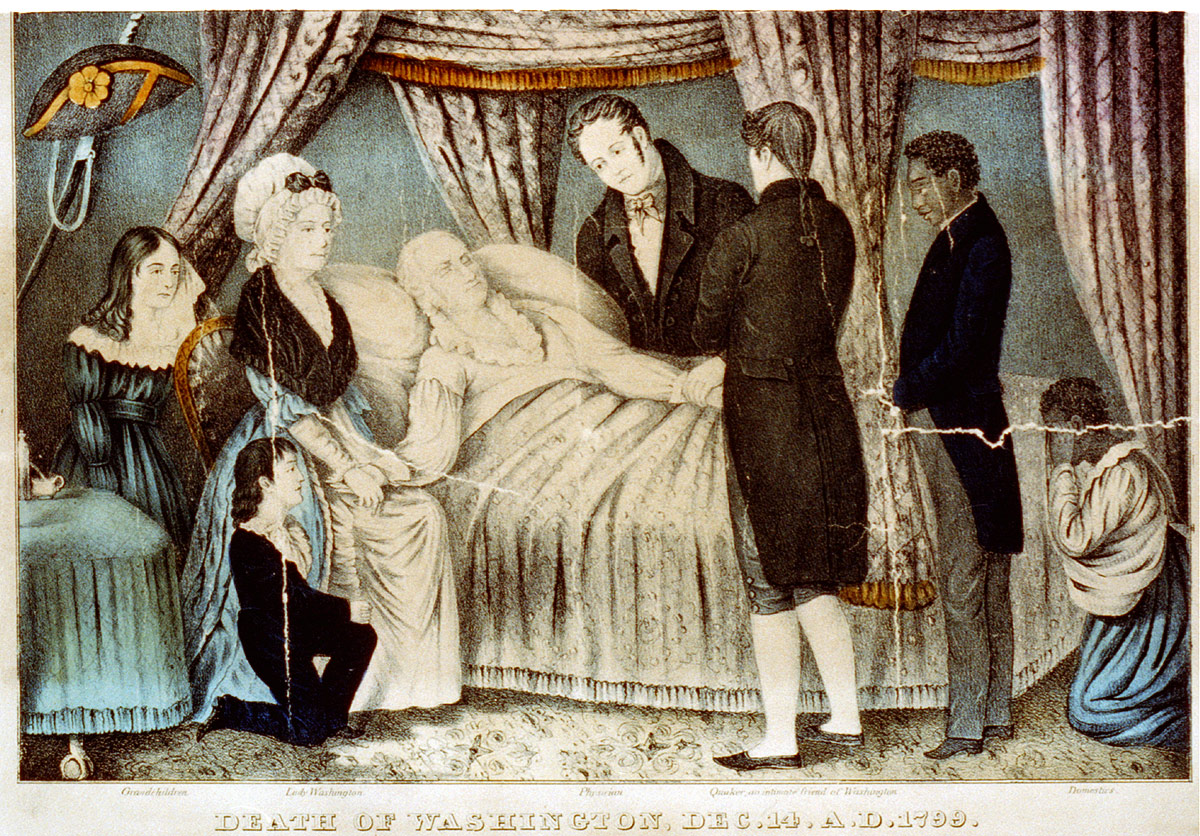

N. Currier (Firm), Death of Washington, Dec. 14. A.D. 1799, c. 1835-1856, lithograph, hand-colored.

The third lithograph, also by Currier, clearly demonstrates the then-common practice of hand-coloring prints.

Images courtesy of The Library of Congress

Behind the Scenes

Death of a President

We all know a lot about Washington’s life, but we rarely talk about how he died. Exactly what killed him is unknown, but detailed records exist of the events leading up to George Washington’s death at his home in Mount Vernon.

Transcript:

On Thursday, December 12, 1799, George Washington was out on horseback supervising farming activities from late morning until three in the afternoon. The weather shifted from light snow to hail and then to rain. Upon Washington's return it was suggested that he change out of his wet riding clothes before dinner. Known for his punctuality, Washington chose to remain in his damp attire. The next morning brought three inches of snow outside and a sore throat for Washington. Despite feeling unwell, he went to the grounds on the east side of his home after the weather cleared to select trees for removal. Throughout the day it was observed that Washington's voice became increasingly hoarse.

After retiring for the night Washington awoke in terrible discomfort at around two in the morning. At daybreak, Martha sent for Washington’s secretary Tobias Lear who found Washington in bed breathing with difficulty. Lear sent for George Rawlins, an overseer at Mount Vernon, who, at the request of George Washington, bled him. Lear also sent to Alexandria for Dr. James Craik, the family doctor and Washington's trusted friend and physician for forty years.

As the morning progressed Washington’s health did not improve.

At four-thirty in the afternoon, George called Martha to his bedside and asked that she bring his two wills from his study. After review Washington discarded one, which Martha burned.

George Washington then called for Tobias Lear. He told Lear, "I find I am going, my breath cannot last long. I believed from the first that the disorder would prove fatal.”

At ten at night George Washington spoke, requesting to be "decently buried" and to "not let my body be put into the Vault in less than three days after I am dead."

Between ten and eleven at night on December 14, 1799, George Washington passed away. He was surrounded by people who were close to him including his wife who sat at the foot of the bed, his friends Dr. Craik and Tobias Lear, housemaids Caroline, Molly, and Charlotte, and his valet Christopher Sheels who stood in the room throughout the day. According to his wishes, Washington was not buried for three days. During that time his body lay in a mahogany casket in the dining room of Mt. Vernon. On December 18, 1799 a solemn funeral was held at the estate.

Text adapted from: George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “The Death of George Washington.” Accessed 7 July 2014. http://www.mountvernon.org/employees-navigation-level-1/encyclopedia-top-level/personal/death.

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

When do you think this painting was made? Right after George Washington died or many years later? Junius Brutus Stearns made a series of paintings, like a timeline, of the first President’s life. The paintings were made to honor Washington 50 years after he died.

If this was the last image of George Washington’s timeline, what would be the first and middle images? Based on what you know about George Washington, describe what kind of images would make up his life story.

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

The Washington Series

This painting is one of a series of five that Stearns proposed in 1849 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Washington’s death. Although he was denied monetary support for his endeavor by the American Art-Union, he pursued his project anyway and produced all five, depicting Washington as a soldier, as a farmer, as a statesman, his marriage, and his death. Despite having been envisioned as a series, only four of the paintings have remained together; The Marriage of Washington to Martha Custis (1849), Washington as a Captain in the French and Indian War (1851), Washington as a Farmer at Mount Vernon (1851), and Washington as a Statesman at the Constitutional Convention (1856) are in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Junius Brutus Stearns, The Marriage of Washington to Martha Custis, 1849, oil on canvas, collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Junius Brutus Stearns, Washington as a Captain in the French and Indian War, 1851, oil on canvas, collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Junius Brutus Stearns, Washington as a Farmer at Mount Vernon, 1851, oil on canvas, collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Junius Brutus Stearns, Washington as a Statesman at the Constitutional Convention, 1856, oil on canvas, collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Photos: Katherine Wetzel, © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

About the Artist

Talk Back

Human or Hero?

In his time, George Washington was regarded as an American hero, as is evidenced throughout Stearns’s series of paintings and the excerpt from Washington’s eulogy below. Is he still regarded this way in 21st-century America?