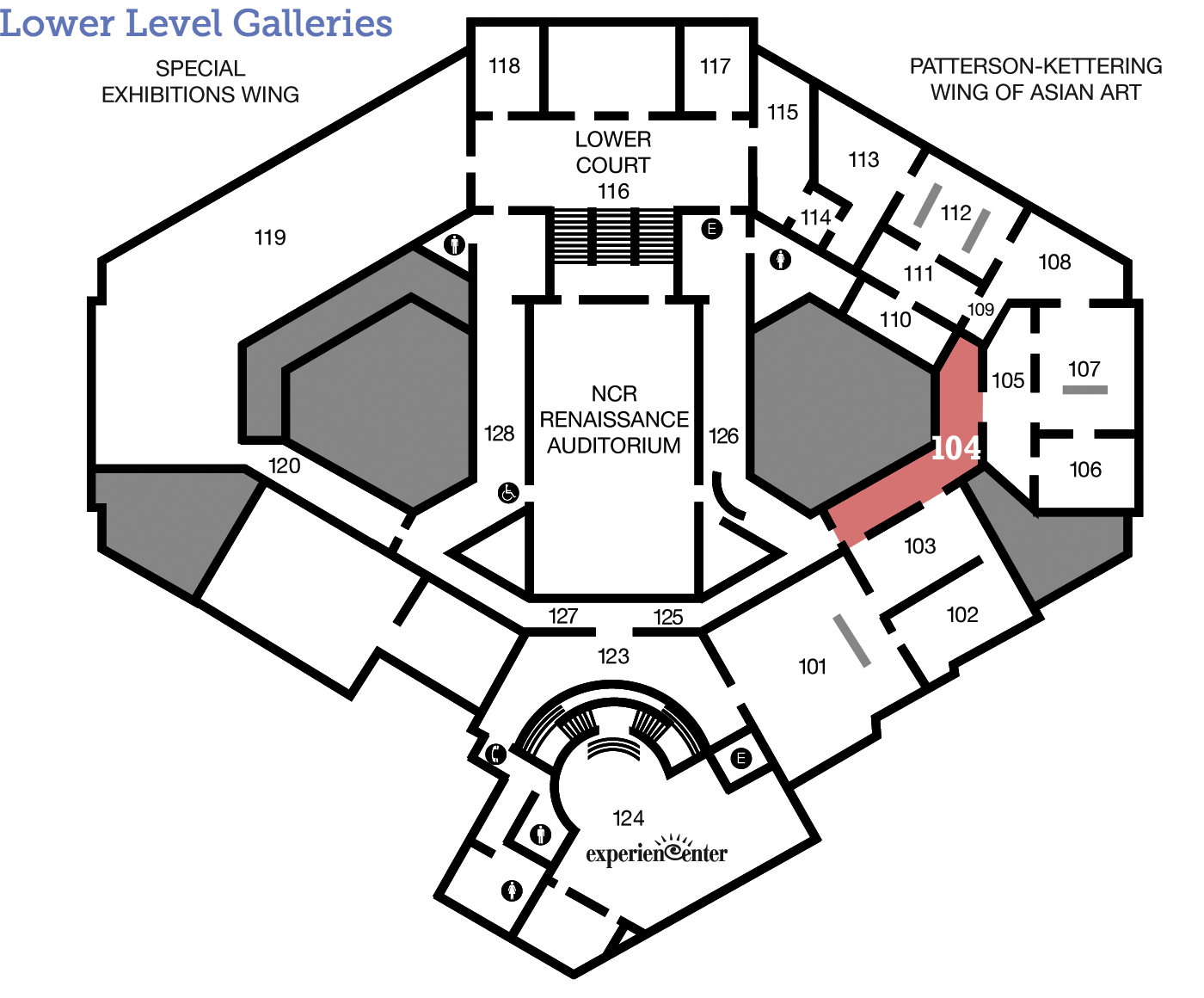

Burmese (Myanmar)

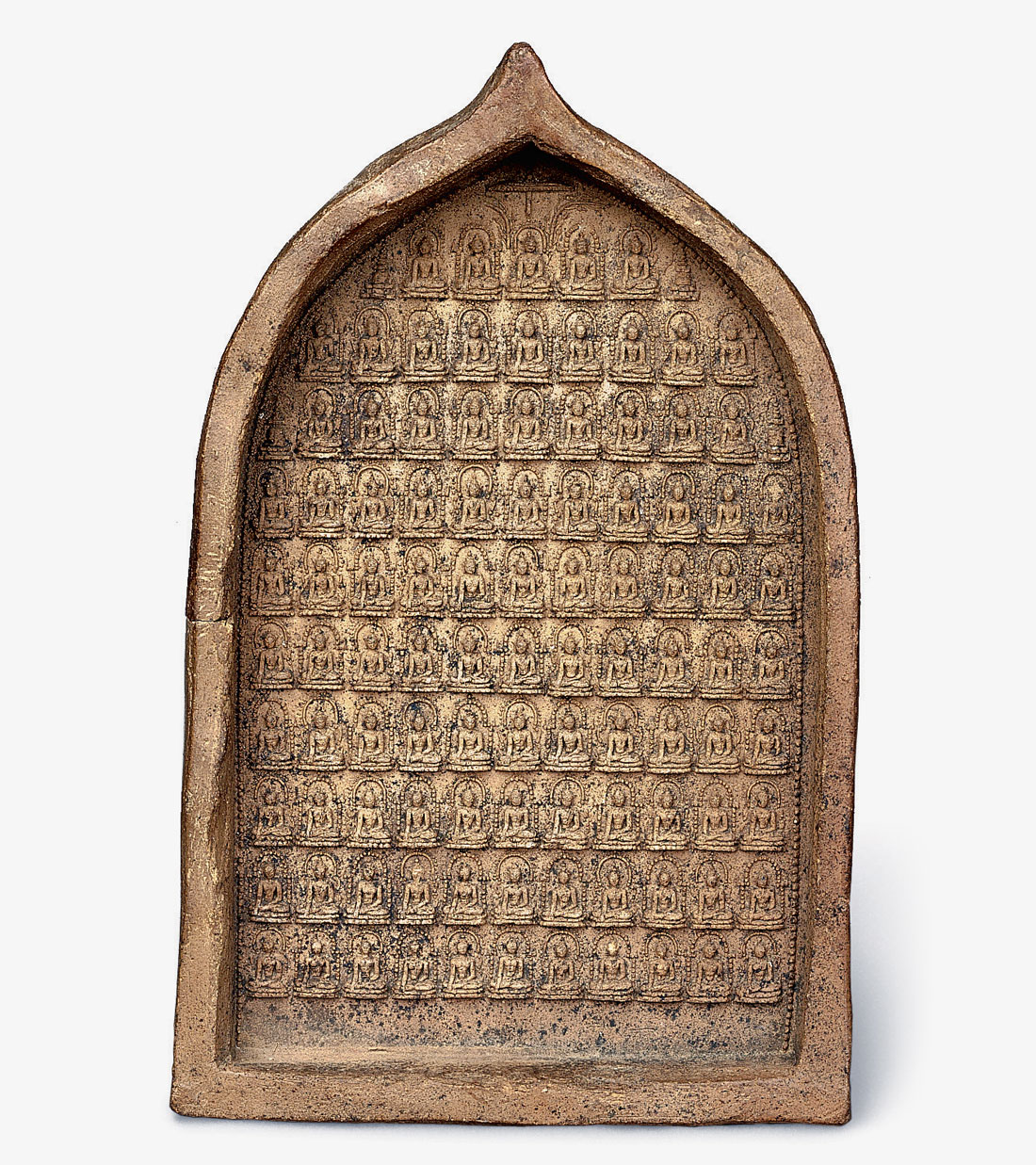

Stele with One Hundred Buddhas

Burmese (Myanmar) 8 ½ x 5 ½ inches Gift of Miss Louise Mellinger 1955.54

Enlightenment in Small Packages

Can you fit universal awareness in the palm of your hand? What about boundless compassion? Look closer at this diminutive clay tablet from Myanmar (also known as Burma) and you may discover traces of Buddha and the devotion he inspired.

A Day in the Life

A Token of Thanks

How do you give thanks? Small clay tablets impressed with images of the Buddha were a popular form of expressing one’s devotion to the Buddha during the Kingdom of Pagan, a two hundred year period of vibrant Myanmar (Burmese) culture (1057–1287). Often an inscription would be written in the space at the bottom or on the back, giving the name of the donor and a pious message. Normally these tablets were left unpainted, although it is possible that colors were added occasionally.

Devotion had a political angle as well. Some of the remaining tablets are inscribed as gifts from rulers, such as Aniruddha (c. 1044–1077), the first king of Pagan who unified Myanmar. Tablets like this one, with one hundred Buddhas, are associated with the king Sri Tribhuvanadityapavara (also known as Alaungsithu, reigned c. 1113–1169/1170?) and some appear with his name. Unfortunately, there are no apparent inscriptions on this tablet.

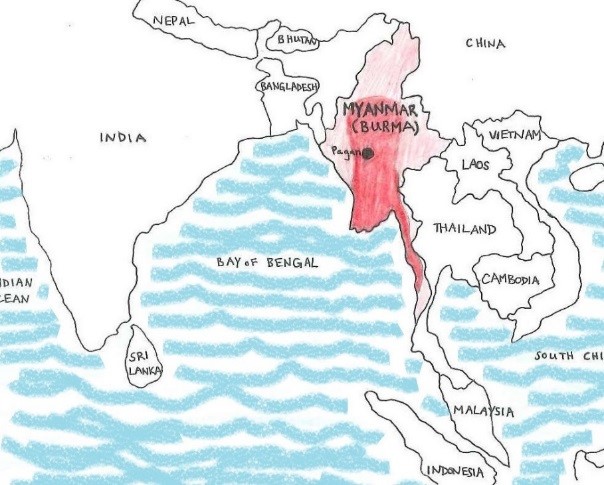

This map of modern East Asia shows the current area of Myanmar in pink. The general area of the kingdom of Pagan at its peak, around 1200 CE, is in red.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

What’s Back There?

Museums are challenged to present objects in a way that is both safe for the object and accessible for the visitor. The mounting on the back of this tablet shows one ingenious solution.

Detail

This mount uses a spring system that has many benefits: it is safe because the spring self-adjusts the tabs, providing the right pressure against the object; it is accessible, allowing the object to be hung at eye-level for the viewer; and it is convenient because it does not require mechanically fastening the opposing tabs to create tension. The mount was designed by Mike Bir, Associate Director of Facilities for Exhibition Construction & Installation at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, who also assisted in mounting other objects in Dayton’s Asian collection, including the large Chinese Relief with Design of Dragons.

Thank you to Martin Pleiss, Exhibition Designer and Chief Preparator at The DAI, for supplying information on the background of this mount.

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

A stele is a monument individuals and families used for religious devotion. It is not known why there are 100 small Buddhas on this stele. Why do you think the artist chose to create 100 identical Buddhas?

Look at Giovanni Francesco Toscani’s Madonna of Humility in Gallery 220. Do you notice any similarities or differences between these two works? How were they used? What are they made of? Who is depicted on them?

Giovanni Francesco Toscani (Italian, 1370–1430), Madonna of Humility, c. 1410, tempera and gold leaf on poplar, 26 ¾ x 18 ¼ inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Elton F. MacDonald 1957.142.

Signs & Symbols

Remembering One's Roots

Although this tablet is from Myanmar the unique imagery and form connect it to Buddhism's Indian roots. Together these different features emphasize the founding event of the Buddha's enlightenment and testify to the continuing expansion of the Buddha Dharma (law or teaching) into new places. Tap on different highlighted parts of the tablet to learn about what they mean.

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Buddhas, Buddhas, Everywhere!

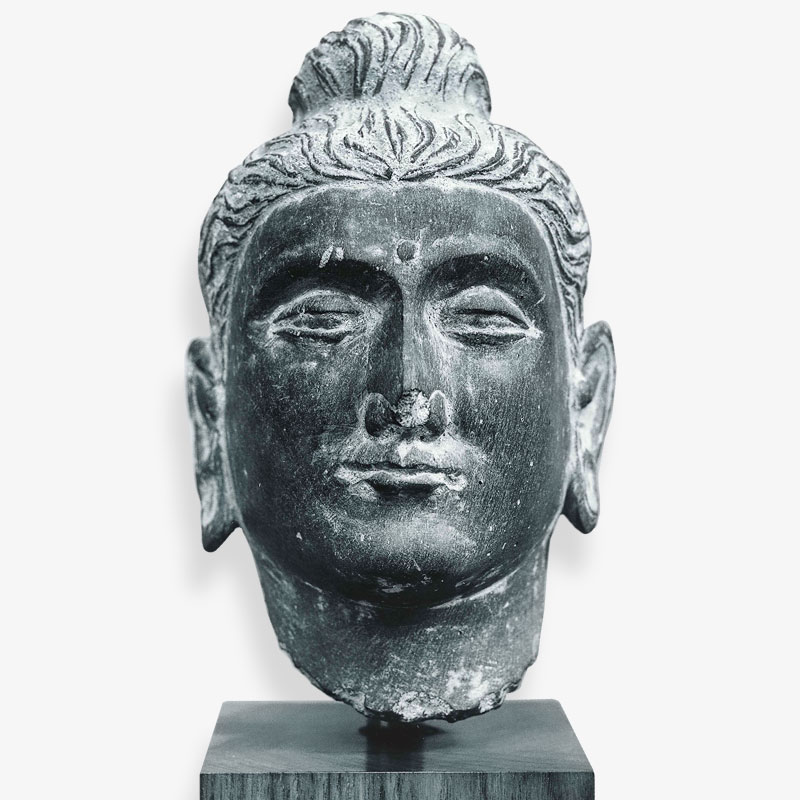

From its origins in India, Buddhism spread to South East Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. The Dayton Art Institute’s Asian art collection contains examples of Buddhas from many of these regions, including this one from Myanmar and others from Japan, Thailand, and India. Look closer at each and consider how differences in scale, material, and shape effect your understanding of the Buddha and the feeling you get from each one.

Japanese, Amida Buddha, 12th–13th century, wood with lacquer and gilt, 35 x 30 x 26 inches. Gift of Mrs. Harrie G. Carnell, 1935.1.

Thai, Head of Buddha, 8th–9th century, grey sandstone, height: 9 ¼ inches. Gift of Mrs. Virginia Kettering, 2000.70.32.

Indian, Head of Buddha, 2nd century CE, grey stone, height: 7 inches. Gift of Mrs. Virginia W. Kettering, 1986.232.

About the Artist

Talk Back

Size Matters?

Often we think of a masterpiece as something that is large, expensive, and unique, like the French sculptor Rodin’s statue of The Thinker. This tablet is small, made of a cheap material, and was mass-produced from a mold, yet it has a significant presence. What do you think are the most important features that make something a masterpiece?