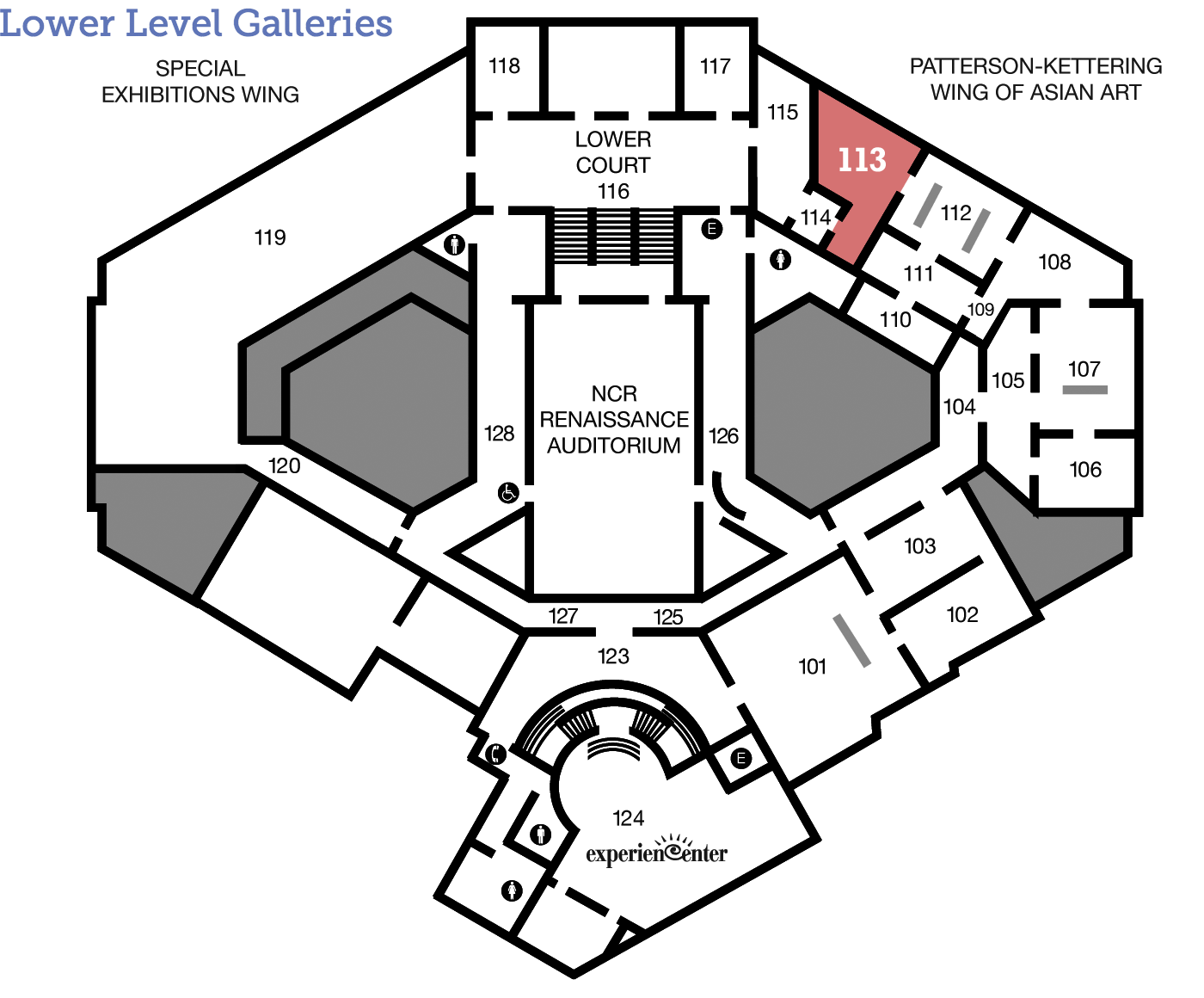

Western Han Dynasty

Tomb Wall Tile

Chinese terracotta with stamped decoration Museum purchase with funds from the Honorable and Mrs. Jefferson Patterson 1959.144

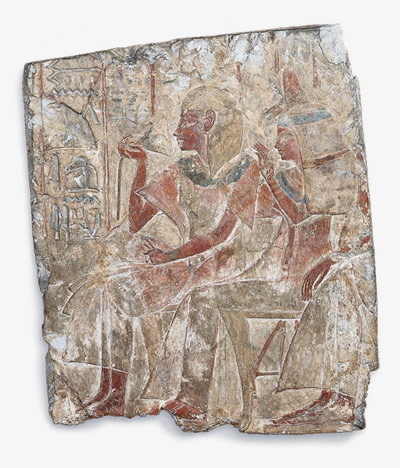

Interior Designing for the Dead

After you die, what would you like to be surrounded by? Pictures of your pets and loved ones? A big-screen TV? This lively clay tile helps us understand what people in China two thousand years ago thought about death and what would be an ideal resting place.

A Day in the Life

An Empire Greater than Rome?

This tomb tile was made during the Western Han period (206 BCE–9 CE), a very important time in Chinese history. Listen as Christopher Agnew, assistant professor of history at the University of Dayton, talks about the epic achievements of the Han.

Transcript:

“So the Western Han Dynasty refers to the first half of the Han, which is the empire that runs China from roughly 206 BCE all the way to 200, 220 of the Common Era. It’s a dynasty that is extremely important in establishing many institutions that have long-standing influence in subsequent Chinese dynasties.

Politically, this is a dynasty that deals with internal and external threats. Internally, the dynasty has to deal with centralizing political control through all kinds of measures: standardization of weights, standardization of coinage, of language, of unitary law code. Externally, they face this constant threat of nomadic invasion and they deal with this in a kind of innovative way, by conquering—particularly in the reign of Emperor Wu—territory in Central Asia, establishing control over trade routes and so on.

This is an era intellectually where we see the integration of Confucianism as an official ideology of the state. So, Confucian classics become canonical, the state supports arts and literature through the establishment of an imperial academy, and we see the articulation of a kind of imperial Confucianism with the philosophy of Dong Zhongshu.

Economically, the Western Han is a flourishing agricultural and commercial economy. The state encourages throughout the Dynasty agricultural innovations, they create innovative ways of taxing commerce through commercial taxes and official monopolies.

Overall, the Han Dynasty, in the long term, […]becomes a kind of model for subsequent dynasties for […]two millennia for how to govern an empire in China. It’s a contemporary empire to the Romans and every bit an equal in power and strength.”

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

This large tile is one of many that would have lined a Chinese tomb underground. Animals were popular symbols and often found on the tiles.

Pretend this tile is the first panel in a comic strip. Finish the comic by creating other panels. Use the animals as characters. Think about the story you want to tell in your comic strip. Will the characters go on an adventure or solve a problem? What will the characters say to each other? Will they meet anyone else?

Signs & Symbols

Animal Planet

Two of the animals on this tile are part of the Five-Phase (wu xing) cosmology that was prevalent during the Han era. This was a way interpreting the world by creating a network of associations among different things in the universe, such as natural elements, animals, planets, colors, seasons, and shapes. The birds depict the Vermilion Bird, which is associated with the south and summer. The cats represent the White Tiger, which is associated with the west and autumn. Most likely, other tiles in the tomb included two more animals, the Green Dragon and the Black Warrior, an intertwined snake and turtle, which represent east/spring and north/winter respectively. Horses were also popular animals to represent in tombs because of their association with the elite and war.

Dig Deeper

What is Death Like?

During the Western Han period there were many ideas about what happens when you die. They thought a person has two souls, the hun and po. The hun is the spiritual soul and the po is the physical soul. When you die these two souls separate and the hun goes on a journey to another world while the po stays with the body underground. The world underground was thought to be like life on earth, so graves were designed to be similar to houses. Dug horizontally into the ground, the tombs were lined inside with clay tiles, like this one, and often decorated with various pictures such as animals or the deceased person. The tombs were then filled with clay replicas of objects and people that were needed for daily life. If you’re standing in the galleries, one example of these replicas is the woman just to your left and pictured below.

Chinese, Female Figure, Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE), earthenware. Gift of Virginia W. Kettering, 1996.25.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Design Your Own Exhibition!

If you were a guest curator for The Dayton Art Institute, which other “What is a Masterpiece?” object would you put side-by-side with this tomb tile and why?

Archaemenid, Relief Fragment from Persepolis, 1967.60. Louise Nevelson, Untitled, 2003.7 Egyptian, Noble Couple Relief, 1972.48 Tang Dynasty, Ritual Bottle, 1935.23

Archaemenid,

Relief Fragment from Persepolis,

1967.60

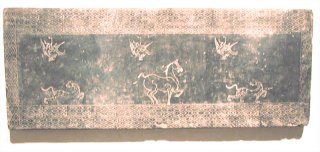

Louise Nevelson,

Untitled,

2003.7

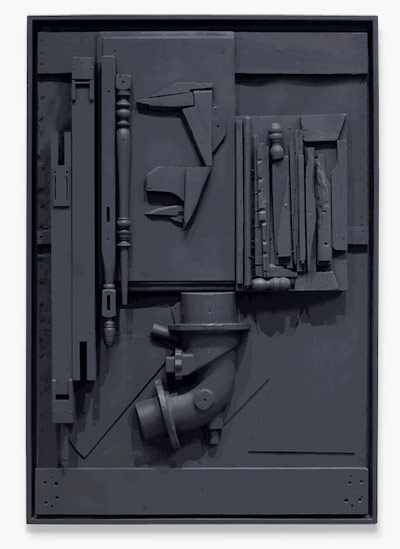

Egyptian,

Noble Couple Relief,

1972.48

Tang Dynasty,

Ritual Bottle,

1935.23

About the Artist

Talk Back

In Memoriam

This tile suggests that, just like today, a lot of work went into making a perfect resting place for the dead. How does your appreciation of the tile as a work of art change when you think about its practical use? Can funerals and tombs themselves be considered masterpieces? If so, how?