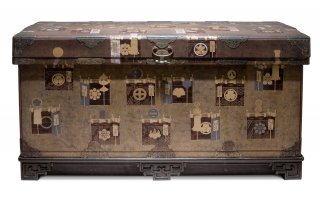

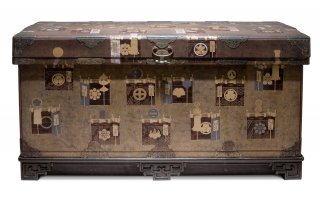

Japanese

Large Chest

(Edo period (1615–1868))19th century Lacquer on wood with gilt, pigments and metal fittings 31 ½ x 60 x 26 inches Gift of Mrs. Julia Davidson Cheshire, Mrs. Frances Davidson Bortz, Mrs. Mary Davidson Swift, and Mr. Stuart C. Davidson 1961.89

More than Meets the Eye

This large lacquered chest is a fascinating and unique work of art, but perhaps not for the reasons you might think. On the surface are the crests of several important samurai. Who could it have been made for?

A Day in the Life

Samurai Lifestyle

Quiz

These three objects are in The Dayton Art Institute’s Japanese collection. Which one would not have been used by a samurai?

Try again!

A dish like this would have been used in the tea ceremony, a popular pastime for cultured samurai.

Correct!

This chest is a nagamachi, a container for storing various household items. Even though the chest displays the emblems of important daimyo (powerful land-holders from the samurai class), there are various details—such as how some of the names are given—that depart from samurai etiquette. This suggests the chest was made by and for a popular audience that was unfamiliar with such formality.

But other details indicate this chest was probably not even meant for normal use. Nagamachi chests were usually stored out of sight, covered, and were not highly ornamented like this chest. Also, they did not have a footed base like the one here. For these reasons, the chest was most likely made for foreigners who would value the exotic look and display it.

(This assessment is based on research provided by Mr. Toshinobu Tokugawa, Director of the Tokugawa Reimeikai Foundation in Tokyo, in a letter to The DAI from February, 1984.)

Try again!

A set of two swords, one long and one short, was essential equipment of any samurai during the Edo period (1615–1868).

Tools and Techniques

The Arduous Art of Lacquer

This chest is covered with lacquer, a labor-intensive finish that uses resin from a poisonous plant. Used for everything from furniture to sculpture to dishes, lacquer is a treasured craft in Japan and other Asian countries. How is lacquer made and why is it so challenging? Watch the following video from the Asian Art Museum to find out. Then look around the Asian galleries and see if you can find other examples of lacquerware.

Copyright 1987, Toshi Washizu

Transcript summary:

Developed over 7000 years, lacquer is an art of patience. Raw lacquer is sap that is gathered from the tree rhus verniciflua [lacquer tree]. Notches are cut into the bark and the sap is collected. A mature tree may only produce a half of a cup of sap in a season. The sap contains a toxin that may cause severe skin irritation (it is a close relative of poison oak), and craft workers must build up immunity through graduated exposure over time. When lacquer hardens it creates a durable surface that is resistant to moisture, heat, salts, and even acids. The material can be painted, carved, and molded, making it a flexible artistic material.

Wood is commonly used as the base of a lacquer object. It may be dried for up to seven years to ensure it will not warp or crack. The core maker—or kijishi—uses a lathe to refine the base to a shape that is one or two millimeters thick. The lacquerer—or nushi—applies various layers of pure lacquer, lacquer mixed with clay, lacquer mixed with earth or ash, and colored lacquer. Sometimes a layer of fabric may be added. The lacquer must be applied in very thin coats, because if it is too thick it will not dry consistently. Technically, the lacquer is not drying but curing, a chemical reaction in the lacquer that takes place in a moist environment, ideally about 85 percent. It is the enzyme laccase in raw lacquer that acts as a catalyst for oxidization and produces the hard surface. After the lacquer is applied the objects are stored in a cabinet where the humidity can be controlled. Then, after each layer, the lacquer must be carefully polished by hand. One craftsman comments, “We should not be called lacquer makers; we should be called lacquer polishers, since that is what we spend most of our time doing.” Over 30 layers of lacquer may be applied and polished over a period of months or even years. The result is a sensuous shape that is made by hand and meant to be felt by the hand, not merely appreciated by the eye.

Decoration may be applied in various ways. In one, known as maki-e (sprinkled design), a drawn design is transferred to the object, redrawn with lacquer, and dusted with powdered gold or silver into the wet lacquer. Other techniques include painting a decoration with lacquer directly, inlaying mother of pearl, or applying gold leaf to an incised design. Beneath the final surface lie hours of intense labor, training, imagination, devotion to detail, and patience.

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

Look at the Blanket Chest in Gallery 208. Both chests were made in the 18th century, but are from different countries. Do you think they were used for the same purposes?

The Blanket Chest is a German tradition passed onto the immigrants, who moved to the United States. The chests traditionally were made for teenagers to house their clothes, blankets, and personal objects. However, this large Japanese chest was most likely made to be sold in Europe and America.

Signs & Symbols

Name Brand

What are all the different shapes on this chest? They are mon, emblems that represent a group such as a clan, family, or business, similar to heraldry or family crests in Europe. Mon were used as early as the 12th century to distinguish friend from foe on the battlefield. They also served as decorative motifs on items ranging from clothes to buildings, and are still used today. The mon on this chest represent important daimyo, large landholders from the samurai class. They appear on an army camp curtain along with an army banner that would further identify the daimyo (this may use a secondary mon). At the center of the lid is the mon of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542–1616), the shogun who moved the capital to Edo (modern-day Tokyo), initiating the largely peaceful and insular Edo period (1615–1868) that would last for over 250 years.

While mon were put on various items owned by those in the samurai class, the representation of so many mon on this chest—along with other details, such as the unusual way some of the names are given or the decorative base of the chest—indicate that it was probably made for a Euro-American audience who would be attracted by the exotic look.

Mon often represent things from the natural environment—such as flowers, plants, or animals—but human-made products and abstract shapes are also common. Tap on the different points below to see what some of the mon represent.

Further reading: John Dower, The Elements of Japanese Design: A Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry & Symbolism, with illustrations by Kiyoshi Kawamoto (Boston: Weatherhill, 2005).

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Cultural Comparisons

The DAI’s permanent collection has furniture from many times and places. If you are in the museum, look for the early American Blanket Chest in Gallery 208. It is about the same size as this Japanese chest and was made just a little earlier. Look closer at both and notice the different surface finishes and decorative techniques.

Poll

If you were to use one of these chests in your home, which one would you prefer?

American (Southern Pennsylvania), Blanket Chest, 1790, poplar, painted with brass pulls. Gift of the Estate of Mr. Elmer R. Webster and Mr. Robert A. Titsch, 1995.52.

About the Artist

Talk Back

What is the Import of an Export?

This chest was most likely made for a foreign audience and was not meant to be used as a normal storage chest. How does knowing this affect they way you look at it? Are the products members of a culture produce for outsiders somehow less important or less authentic than the products made for their own use?