Chinese

Standing Bodhisattva

Limestone Height: 32 inches Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Nathaniel Soifer 1961.98

Ready for the Runway

Sinuous lines, glamorous jewelry, and a mysterious expression. This sixth-century Chinese sculpture showcases a fresh style both unique to the time it was made and timeless in its expression of a path to true beauty.

A Day in the Life

Shifts in Style

Artistic styles develop in specific times and places. What does the style of this sculpture tell us about when and where it was made? How is it different from the Buddhist sculpture that came before it? Art historians Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Jennifer N. McIntire of Smarthistory use visual cues to answer these questions. Watch the following video to learn more as they discuss a similar sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Smarthistory, 2015

Selected transcript:

Dr. Beth Harris: It’s interesting how much we can tell about it, but how much about it is still really in dispute by scholars. The styles of art that we see in art history are so often connected to the historical circumstances—often politics, the government—and we know that the period before this was called the Northern Wei, which had a really different style.

Dr. Jennifer N. McIntire: Yes, what happened is in the Northern Wei the style that was predominant was weightless and very linear. Important examples can be found at the cave temple complex of Yungang, where in Cave 6 you would see a buddha or bodhisattva image that shows no attention to the body form, but a lot of attention to folds and line of the drapery; and the shapes are weightless.

BH: So that period known as the Northern Wei is about fifty years before this, and is a relatively stable time in parts of China….

JM: Particularly in the north, absolutely.

BH: And then a period of political upheaval follows.

JM: And the two strong dynasties that emerge in the north are the Northern Qi in the east and the Northern Chou in the west. And this is a very interesting bodhisattva example when you’re thinking about that time period. There are some characteristics here that really indicate the Northern Qi, but others that indicate the Northern Chou—and granted, there’s a lot of overlap between the styles of buddhas and bodhisattvas that come out of these two dynasties. One thing is this incredible opulence in terms of the drapery and jewelry, details that are often associated with the Northern Chou. The other aspect that is Northern Chou is the really square shape to the face, the block-like features. Both the Northern Chou and the Northern Qi broken away from this Northern Wei aesthetic of weightlessness and show the bodhisattvas and buddhas with a lot of three-dimensional and geometric form.

BH: This figure is anything but weightless. So we’re really talking about dynasties, different historical periods, and different regional styles emerging in different places, and art historians really needing to study each of those places and the art that emerges and then comparing and contrasting to date and to locate a lot of these early figures. Buddhism had only come to China a few hundred years earlier, from India, and in that few hundred years the styles that developed in Buddhist art are really dependent on those different regions, and the different dynasties, and therefore there’s so much change going on.

JM: And this is an interesting example of that because we see here this very abrupt break with the weightless, linear aesthetic of the Northern Wei to this much more volumetric, massive form that is associated with the Northern Qi and Northern Chou. The source for this change is often identified as Gupta, in India—the sensuous Gupta style.

BH: It’s really a puzzle in so many ways.

JM: It is.

BH: So, it’s important to imagine it in its original context—within a temple—sensuously painted and in that kind of religious-spiritual context.

JM: Yes, and in a much darker environment, as well, and surrounded by other sculptures and paintings.

Tools and Techniques

The Statue is Naked!

Take a close look at the subtle coloration in the surface of the limestone used to sculpt this 6th century Standing Bodhisattva. This would have likely been covered up with brightly colored paints when it was on display in a temple some 1,500 years ago. How would you prefer to see it?

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

How to Tell a Buddha from a Bodhisattva

Buddhist art can be very confusing if you are new to it. For example, there are various spiritual figures, including buddhas and bodhisattvas. What is the difference? A buddha has achieved enlightenment while a bodhisattva has willingly postponed enlightenment in order to help others in this world. How can you tell the difference between these figures visually? Find out by trying to answer the questions below. Then look closer at this sculpture and others in the Asian galleries and try to determine if they are buddhas, bodhisattvas, or some other figure.

Quiz

1. Has long hair, often piled up in a sophisticated fashion.

Buddha.

Bodhisattva.

2. Wears simple robes with no jewelry.

Buddha.

Bodhisattva.

3. Poses with a “gift-giving” hand gesture—a hand pointed down, palm facing outward.

Buddha.

Bodhisattva.

Just for Kids

Try it!

A bodhisattva is a person in Buddhist teaching who has reached a state of peace and contentment. How might you describe the emotions of this bodhisattva?

Take the sculpture’s pose! Partner up with someone to help each other get it right or use a mirror to make this pose. Make your face look like the sculpture’s. One hand is missing. How do you think the hand was posed?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Stand Up, Stand Out

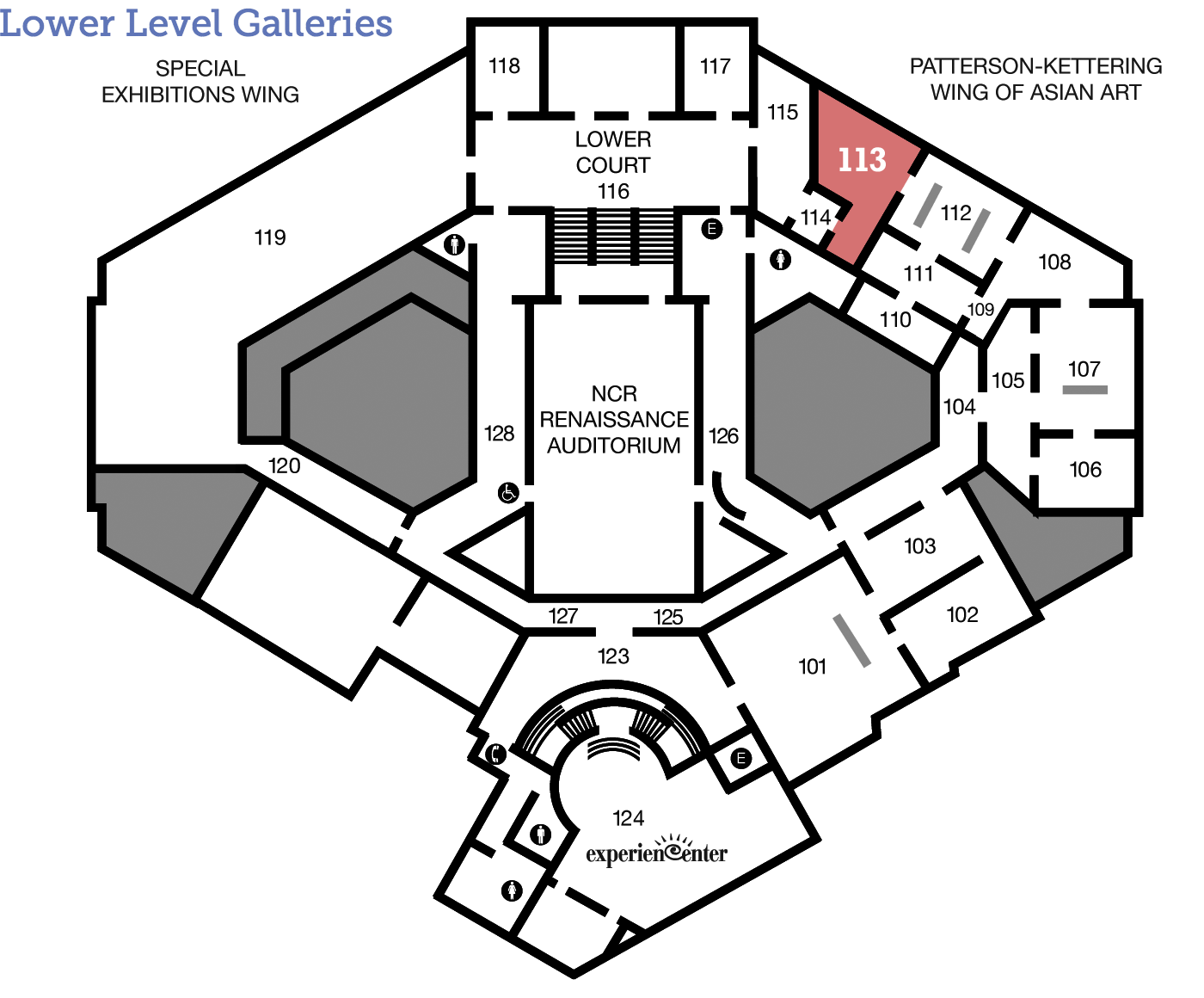

What are some of the unique features of this sculpture and how does it contrast with another bodhisattva in The DAI’s collection? Listen as Lisa Morrisette, an Asian art specialist and manager of school and docent programs at The Taft Museum of Art, explains more.

This figure is a bodhisattva—a Buddhist deity who has reached enlightenment, but rather than enter nirvana vows to remain on earth to help all sentient beings along the path to enlightenment. Bodhisattva are recognized by their princely garb in contrast to the monastic robes that the Buddha normally wears. This figure’s dress is typical of Indian costume, not Chinese. Attired in a dhoti, a kind of skirt, with scarves draped around the chest and flaring off the edges of the shoulders, this aspect of costume reminds us that Buddhism is an imported foreign religion in China. This princely ensemble is further adorned in jewels. If you look closely at the ears, you can see earrings incised on the surface, and around the bodhisattva’s neck are a cascade of long and short necklaces. The hair is piled atop the head and crowned with jewels. Incised upon the open palm of the hand is a single flame-shaped jewel. One hand is missing, but together both hands originally formed a mudra, a hand gesture communicating “fear not” and “gift-giving.” The face, with its sweet smile and downcast eyes, creates a sense of serenity. Both face and hands are somewhat exaggerated in size, emphasizing the compassion of the bodhisattva. The flowing, incised lines of the scarves and skirt lend a delicate grace to the columnar Sui dynasty style. [Compare this figure to another bodhisattva in The DAI's collection, the Torso of Bodhisattva from some 200-300 years later.] Also attired in princely dress, this bodhisattva stands in a posture with the hip thrusting out to the right of the body, forming a graceful S-curve. Complementing the posture, the drapery is more deeply carved than the Sui example, and the body more fully modeled with a softer, fleshier quality. The juxtaposition of these two figures allows us to see and compare differences in period style.

Look Around

About the Artist

Talk Back

A Sign of the Times

This bodhisattva has a Chinese-style face and Indian clothing, highlighting the fact that Buddhist art often developed through the convergence of different cultures. Art often has the power to cross borders and unite different things. Where else have you seen this happen?