(In the style of) Hopewell Culture

Owl Effigy Pipe

Native American North American pipestone 2 ¼ x 3 ⅜ in. Museum purchase 1962.34 128

Bird of Mystery

This owl may be small but it hides a lot! From an enigmatic past association with Native American peoples to an abduction by thieves, the little fellow has many secrets to share, and some it may never tell.

A Day in the Life

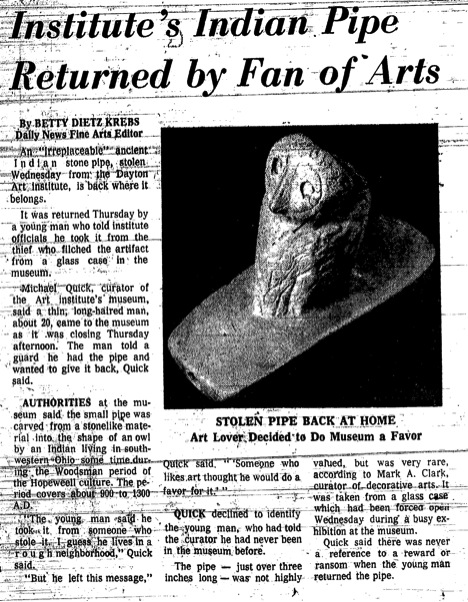

STOLEN!!!

For a few days in 1974 this little owl had quite an adventure in Dayton. It was stolen from The Dayton Art Institute on September 25th and was returned by an anonymous art lover a day later. Read all about it in Dayton Daily News articles from September 26th and 27th.

Used with permission from the Dayton Daily News

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Detective Work

Art historians and archaeologists must often try to determine if an object is authentic, and this can be an ongoing question. Listen as Kay Koeninger, professor of art history at Sinclair Community College, discusses some of the questions surrounding this pipe.

Transcript:

Kay Koeninger:

“We do have some questions about the pipe, and this is often the case with objects in a museum. Art historians and archaeologists really work like detectives. You have a lot of questions and sometimes you have a lot of mysteries that you need to work on. We also have to remember that forgeries of this type of material are really common. So here are some of the questions we have about the pipe.

The first big question is its condition. It’s in really great condition, in fact it looks very new. And this is a puzzlement because most Hopewell pipes that have been found and authenticated were actually broken in a ritual before they were put into the mound. We don’t have a lot of information about where this pipe came from. We do know who collected it and who gave it to the museum. We know that it’s been in several exhibitions, but we still don’t know exactly where it came from in Ohio; we don’t have any notes from an archaeologist about it. Another question is its shape. The owl, if you notice, has its head turned a hundred and eighty degrees. This type of position is also found in another pipe in the Ohio Historical Society. The last question is this. When you compare it with other pipes at the Ohio Historical Society the carving of the feathers on the outside is done in a totally different style.

So, lots of questions to work on! And one thing you can think about right now is […] this: ‘If this pipe is not authentically Hopewell, how does that change your perception of it?’”

To see a picture of the owl pipe in the Ohio Historical Society collection that Professor Koeninger mentions, click here

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

The Hopewell culture was a group of Native Americans. They lived in parts of Ohio from 200 BCE to 400 CE. The Hopewell Native Americans are known for their farming and large earthworks, like the Great Serpent Mound.

Different cultures throughout history have related animals with characteristics. For example, owls are known for their wisdom and lions are known for bravery. Look around the museum for animals. How would you characterize the different animals you see? Share and compare the traits you gave the animals with a friend. Did your friend give the animals the same traits?

Signs & Symbols

Owl-fully Nice!

Why is this pipe carved in the shape of an owl? Listen as Kay Koeninger, professor of art history at Sinclair Community College, talks about the significance of the owl in Native American culture.

Transcript:

Kay Koeninger:

“Why is the animal on the pipe an owl? In Hopewell art, birds and bird motifs are very popular; they are found on pottery decoration and other objects, including pipes. One of the most famous Hopewell sculptures is a bird claw carved from mica, which is in the collection of the Field Museum of Chicago. You may then wonder, ‘What does the owl symbolize?’ We really don’t know. But based on our own experience of owls, we can come up with some logical theories. Birds appear to be almost magical creatures, as they have the gift of effortless flight, a talent not discovered by humans until very recently! They go to places that we don’t see and then they return. And owls, with their nocturnal life and haunting cries, are very distinctive birds. They are also ferocious hunters, a trait that was probably greatly admired by ancient Native American people. Historically, the Native American worldview generally includes a view of nature in which animals and humans are of equal status. Important spiritual qualities are assigned to animals, and human success is often tied to having an animal spirit as a guide or mentor. Perhaps the owl held this status for the maker of this pipe.

Even though many mysteries about this pipe will probably never be solved, we can still appreciate the skill of the artist who made it. The stone is expertly carved and polished. The essence of an owl is captured here, despite the small scale.”

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

About the Artist

Who Were the Hopewell?

Who were the Hopewell people? Why did they make pipes? How did they make them? In this video Kay Koeninger, professor of art history at Sinclair Community College, helps us better understand this tiny pipe and the people who made it.

Transcript:

Kay Koeninger:

“There are many intriguing questions about this beautiful carved stone pipe. First of all, let’s start with what we know. This pipe may be from the Hopewell Culture, an ancient Native American culture that was located in the Ohio Valley from approximately 200 BCE to 400 CE. One of its centers was in present-day southern Ohio, with another focus in Illinois along the Mississippi River. It was obviously a complex culture, based on the fact that its people built many imposing earthworks, which are often filled with beautiful objects including shell, obsidian, animal teeth, copper, clay pottery, and stone. Some of the earthworks contained graves and since some of these graves are more elaborate than others, we can theorize that the culture had a hierarchy, or a class of honored leaders. Some of the better-known Hopewell earthworks in Ohio include those in Chillicothe, Circleville, and Newark. Closer to Dayton, the Miamisburg Mound dates from the Adena Culture, which came before Hopewell, and the Great Serpent Mound near Hillsborough was constructed by the Mississippian Culture, which followed the Hopewell.

Carved stone pipes are often associated with Hopewell earthworks. Many of them are in the same form as this pipe, which is called a platform pipe. Platform pipes include either a three-dimensional animal form or a plain bowl resting on a curved or horizontal platform. The term ‘effigy’ is used to further describe a pipe with an animal, as effigy means ‘a copy, image, or likeness.’ As the Hopewell artists did not have metal tools, and used flint tools instead, the pipes were made from an easily carved soft stone, such as pipestone, steatite, or chlorite. There is pipestone in Ohio. A smaller percentage of the pipes were made from Catlinite, a soft red stone that was quarried in southwestern Minnesota, and valued as a trade good. Ancient North Americans had highly efficient trade networks that crisscrossed the continent. At one time, pearl inlays may have marked the eyes of the owl on this pipe, based on other examples.

How did the pipe work? The smoker actually looked at the face of the animal when using the pipe. This brings up the question of how tobacco was probably used in this ancient culture. Based on the role of tobacco in historical Native American cultures, we can theorize that tobacco was a part of important religious and social rites. The fact that the smoker faced the animal form also points to the hallucinatory aspects of tobacco and the probable importance of visions in Hopewell religious practice.”

Talk Back

What Makes a Masterpiece?

If this pipe turned out to be a modern reproduction, would it no longer be a masterpiece? Does being a masterpiece only depend on the inherent features in a work or does it also depend on other factors such as who the maker was or when it was made?