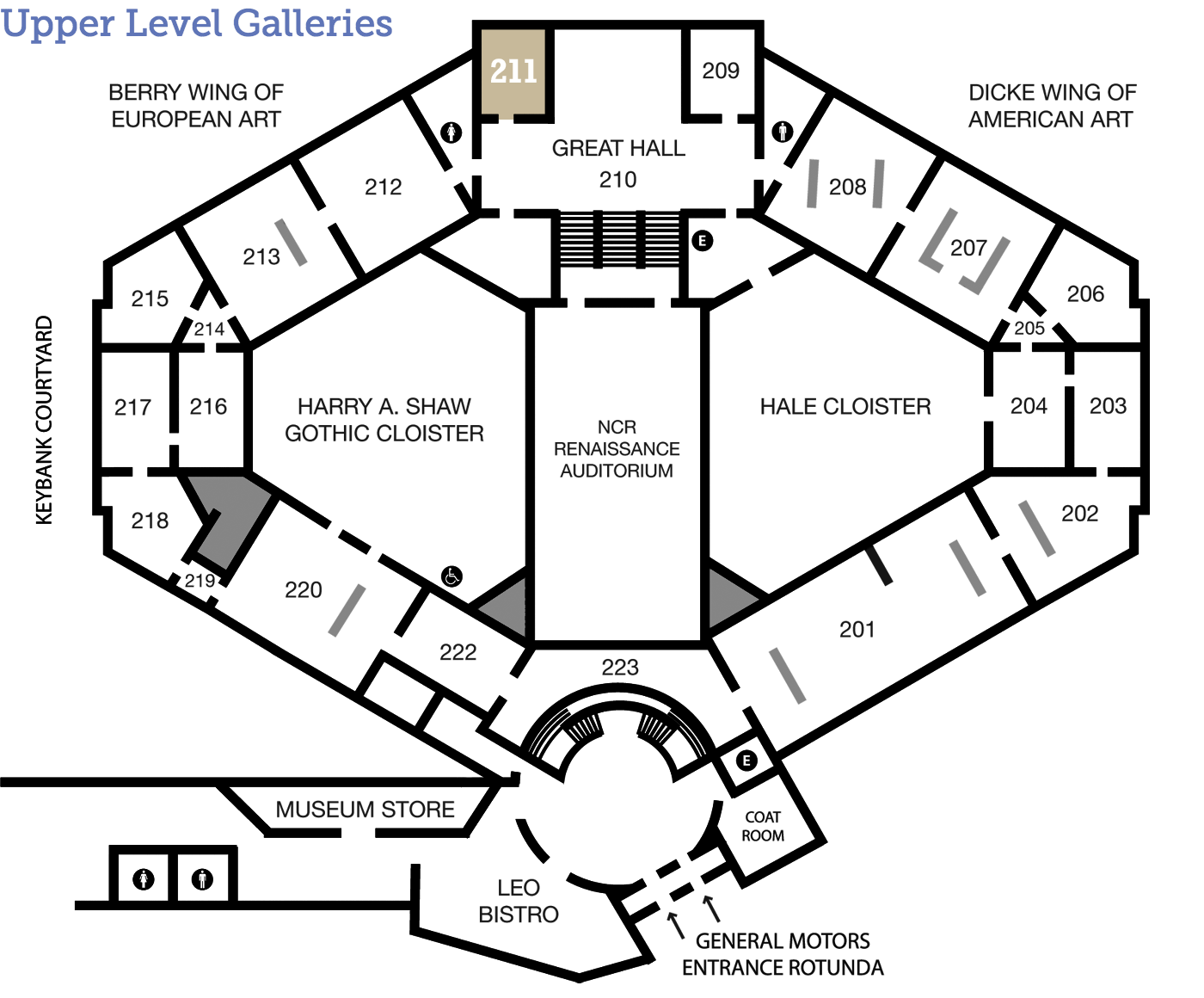

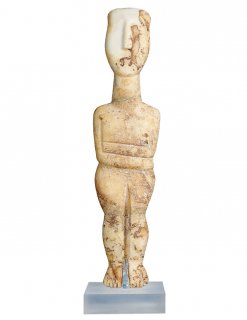

Cycladic Islands

Female Figure

Marble 23¾ x 7 x 6 in. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Associate Board’s 1969 Art Ball 1969.36 211

More Questions than Answers

How do we know this sculpture is female? Why are her toes pointing downward? We may never know the answers to all of our questions, but experts have gleaned a great deal about sculptures like these based on archaeological research.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Form Versus Function

Although we view them upright in museum displays, these figurines were actually found lying horizontally in burial tombs. In fact, they could never have stood up on their own. In the following video clip, listen as Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Stephen Zucker, Emeritus Faculty at the Khan Academy, describe the formal qualities that virtually all Spedos figures exhibit.

Transcript:

Dr. Beth Harris: Not only are the female figures abstract but they’re also very compact. The limbs are folded in, there’s no space between the arms and the torso. There’s no space between the legs, the knees are just slightly bent, there’s no real sense of movement.

Dr. Stephen Zucker: It is a closed composition that emphasizes the overall contour of the figures. Look at the shield-like shape of the face and the way that the nose projects. They’re beautiful without eyes but there were painted eyes. There was a painted mouth. We initially see these as flat but when we spend a moment looking at them, we see that the head is at one angle, the neck at another, then we have the more complicated surface of the torso. And then it seems as if the thighs project outward and the shins inward again, and then of course we have the reverse with the feet. And so there is this almost slight accordion-like folding of the body.

B.H.: With later Greek sculptures we might think about kouroi figures from the 7th century, much later and on the Greek mainland. There we see male figures nude and female figures clothed, and here these female figures are all nude. That has led some art historians and archeologists to speculate that maybe these are somehow related to Neolithic fertility goddesses.

S.Z.: But the key word here is “speculate” because we have no written records. All we have is the object itself. They have been stripped of all of their cultural meaning, and in some ways that is also a very Modernist idea: that we can appreciate the aesthetics, the object itself, unencumbered by what their real meaning was. Video courtesy of Smarthistory.

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

The Cyclades Islands are a chain of islands between Greece and Turkey in the Aegean Sea. Figures, like this one, have been found all over the islands buried in graves. The Cycladic culture had no written language and the meaning of the figures are lost in time. Why do you think the figures were buried in tombs? Do you think they were used for something else?

The figure appears plain and undecorated, but there is evidence that the marble was once painted with facial features and even tattoo-like patterns. How do you imagine this figure might have looked thousands of years ago? Print the head of the Female Figure at home and color her face the way you imagine it looked.

Further reading: J. Lesley Fitton, Cycladic Art (London: British Museum Press, 1989).

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Modern Masterpieces, Ancient Inspiration

Sculpture from the Cyclades islands had a significant influence on the styles and personal collections of several famous Modernist painters and sculptors. G. Max Bernheimer, International Head of Antiquities at Christie’s auction house, discusses links between the Modernist movement in Europe and Cycladic objects like this one. (See "About the Artist" for more about the Cyclades.)

Transcript:

The modern rediscovery of Cycladic art occurred in the nineteenth century when figures were collected by travelers, some eventually finding their way to museums such as the Louvre and the British Museum. Cycladic sculpture was to exert a tremendous influence on the Modernist movement. Artists such as Picasso, André Derain, and Henry Moore were all known to have had a Cycladic figure in their own collection. There can be no doubt that the strength of these small sculptures where the human form was reduced to its barest essentials would serve as the touchstone for these pathfinders, and as such, the Cycladic idol functioned as a cornerstone of Modern art.

The rigorously reduced sculptures of Brâncuși, such as his L'Oiseau dans L'espace, show the influence of the Cycladic style. Picasso thought of his Petit Bonhomme des Cyclades as one of the original artistic spirits of human creation and declared that Cycladic figures were “stronger than Brâncuși. No one has ever made anything so bare.” Modigliani’s stone sculptures evoke the Cycladic spirit; his Tête from 1910-1912 shows the female head boiled down to a harmonious minimum. And Giacometti was exposed to Cycladic art in the 1920s and, in his search for some means of capturing the world through reduced forms that tapped into a core, fundamental truth, resulted in works that strongly recall Cycladic sculpture such as his Homme from 1927-1928.

Used with permission from Christie’s.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Across the Ages

The geometric forms and reduction of the figure like those found in Cycladic art can also be seen in one of The DAI's own modern paintings. Fourteen (1913) by Manierre Dawson (1887–1969) demonstrates the Modernist—and specifically Cubist—interest in the shapes and forms found in Cycladic sculptures. The lines and curves of the Cycladic figure’s features are echoed in Dawson’s reductive use of line and shape. To see Dawson’s painting in person, visit Gallery 203.

Manierre Dawson (1887–1969), Fourteen, 1913, oil on canvas. Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family, 2000.41

About the Artist

The Unknowable Ancient Culture

The Cyclades are an archipelago of approximately thirty small islands in the center of the Aegean Sea between the Greek mainland, Turkey, and Crete. The Cycladic people produced figures like this one between 2700 BCE and about 2300 BCE during the Early Bronze Age, and they have been found throughout the Cyclades as well as in Crete and mainland Greece.

The Spedos type of Cycladic sculpture is characterized as a slender, elongated, reclining human form with folded arms, characterized by a U-shaped head and a deeply incised—but not open—cleft between the legs. Even though they did not have a written language, the Cycladic people who made this figurine left behind evidence of their culture through hundreds of marble sculptures.

Further reading: Pat Getz-Gentle, Ancient Art of the Cyclades (Katonah, NY: Katonah Museum of Art, 2006) and The J. Paul Getty Trust, “Large Female Figure with Incised Toes,” http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=15054.

Map courtesy of The World Factbook.

Talk Back

What Am I?

Because these sculptures were created in a culture that did not have written language, nothing is known for certain about the purpose or use of the female figurines. It has been speculated that they could have been statuettes of female deities, fertility idols, or companions for the dead into the afterlife. What else might these flat, simplified figures have been used for?