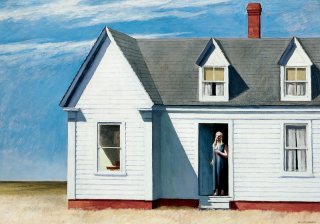

Edward Hopper

High Noon

(1882–1967)

American 1949 Oil on canvas 27 ½ x 39 ½ inches Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Haswell 1971.7

Hopper Country

You may know what time it is, but where are you? Edward Hopper’s paintings, like High Noon, capture the ambiguities of American life in anonymous people and places. They invite us to consider our relationship to others and the spaces we live in everyday.

A Day in the Life

An American in Paris

After attending the New York School of Art, and in between jobs as an illustrator, Hopper lived in Europe for nearly ten months during 1906 and 1907. Spending most of his time in Paris, he was able to see both the old masters and works by recent painters such as Gustave Courbet and Paul Cézanne, as well as experiment on his own by painting the vibrant city life.

During this time Hopper made a series of caricatures of different Parisian people with watercolor paints. Some of these are in The DAI’s permanent collection (not currently on view). In them, you can see both the graphic sense that informed Hopper’s work as an illustrator (see also “Arts Intersected”), as well as hints of the stoic figures that would populate his most well-known paintings.

Further Reading: Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: A Catalogue Raisonné, volume 1 (New York: Whitney Museum of Art, 1995), 41–73.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Standing Around

High Noon is a good example of how art is open-ended; that is, there can be a variety of interpretations. Who is the woman standing in the doorway? What is she doing? Explore how your answers to these questions about the mystery of this quietly intense painting compare to the following audio clip by Will South, Chief Curator at The DAI from 2009 to 2011. As an aside, the model was most likely Hopper’s wife Josephine; she was also an artist and modeled for most of Hopper’s paintings.

Transcript:

Edward Hopper’s figures are often alone, staring out of a window, sitting at a café table, or standing on the porch of a New England house looking out at the ocean. High Noon is such a picture: an anonymous woman is seen in the doorway, although we have no idea why. Is she waiting for someone? Or simply looking out on the day? There is no sense of any activity; she is still and surrounded by a large house that is struck by sunlight leaving dramatic shadows on the roof and walls. The sky beyond is large and empty. Life, Hopper seems to say, is intense—the sunlight is strong and the sky open—but still we are alone and waiting. High Noon is a typical painting for Edward Hopper. In it, he explores patterns of light and dark color that are almost abstract, but he also tells a subtle story about modern living: we may have a large house and time on our hands, and yet still have nothing to do.

Arts Intersected

Edward Hopper, Illustrator?

Many artists are not able to support themselves by simply making the art they desire. Instead, they often have to take up other work that may or may not be related to art. For years, Edward Hopper did illustrations for various magazines primarily for financial gain, as did other American artists such as Andy Warhol, John Sloan, and Stuart Davis. See examples of his striking illustration work and explore how it influenced his paintings in the following video from the Norman Rockwell Museum with Gail Levin, Distinguished Professor at Baruch College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

© Norman Rockwell Museum 2014

Partial transcript:

Hopper really understood what’s in the artist’s mind’s eye is that original way of viewing the world. It’s kind of there from the start; you can train an artist to work in this technique or that technique, maybe to look in a different way, but there’s a certain way of looking that somehow becomes part and parcel of the personality. I really believe that.

I never dreamed I would become the first curator of the Hopper collection at The Whitney Museum with the charge to write the catalogue raisonné, The Complete Works of Edward Hopper, and to organize a major exhibition. When I began that I discovered that Edward Hopper had worked as an illustrator doing commercial work and for magazines, and I realized they had had an influence on his development.

Researching Hopper as an illustrator was really like looking for needles in a haystack, so a lot of evidence that one would like disappeared, shall we say. I was surprised at how large the body of his illustration work was and how much of his time and energy it took up, and about how much of it survived in one form or another—some of it was only available on microfilm at the Library of Congress, which had shredded those magazines, so they’re pretty ephemeral.

Edward Hopper was not the only “fine artist” that had an earlier career in illustration. Illustration was a pretty honorable profession. Today with so much photographic reproduction on magazine covers we have less of the art of illustration than we used to have; it was really very important. For him it was just a way to earn a living which he had not chosen as his dedicated path in life, but that his parents had insisted upon. It was they who wanted him to study illustration and not “fine arts” because they wanted him to be able to support himself—a perfectly understandable, if unreasonable, request for someone like Edward Hopper who really had trouble working under direction. He needed to make art for self-expression and not with someone else’s recipe.

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Another World

At a time when many American painters were making abstract compositions, Edward Hopper continued to paint recognizable people and places. However, these seem to exist in a world of their own. Look at the other paintings nearby that come from the same era as High Noon, such as Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses’ Lake Eden, Vermont, or Charles Sheeler’s Stacks in Celebration. Can you guess the time of day in these? Look closer at how each artist uses light and color to create distinct atmospheric effects.

About the Artist

Monumental Silence

Edward Hopper’s paintings often resonate with viewers for capturing something profound, even unspeakable, about modern American life. What is this? Learn more about Hopper’s distinctive art in the following video from the National Gallery of Art, which includes a clip of Hopper himself speaking.

© National Gallery of Art

Transcript:

Unknown Speaker 1: Everybody thought he was the greatest; he was like a god.

Unknown Speaker 2: He invented or developed a lot of ways of picturing the American experience, which becomes a metaphor for bigger experience.

Unknown Speaker 3: He certainly was a realist in that he painted what he saw. His pictures are made out of facts, certainly, but also memory and improvisation.

Steve Martin: Edward Hopper didn’t belong to a movement, or a group, or a school. The consummate outsider, he belonged to himself. In the 1920s, at the beginning of his career, he painted the plain, unadorned face of America: factories, telephone poles, small-town streets, and touring cars, and he pared them down to the raw essentials.

Red Grooms: In the sense of a white wine, he certainly was a dry white wine—he wasn’t fruity in any way, it’s very sparse. He didn’t do more than he had to. No one, no figurative artist was as bare-bones as he was. In a sense that it perfectly fitted his subject as well—the hotel rooms, the barren offices with minimal pieces of furniture, filing case. I think that’s the extraordinary, thrilling thing that he achieved.

SM: Art critics saw Hopper’s work as the latest chapter in the history of American Realism. They compared him to Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, but Hopper’s paintings lacked their dynamism and verve. That restraint seemed to come from within. Even his closest friends found the six-foot seven-inch Hopper a little daunting.

Unknown Speaker 4: Hopper had no small talk. He was famous for his monumental silences, but, like the spaces in his pictures, they weren’t empty.

SM: Hopper was equally deliberate about his paintings. He worked hard, and his ideas came to him slowly.

Edward Hopper: It’s very hard to define how they come about, but it’s a long process of gestation in the mind. Arising emotion, I suppose.

SM: As the confidence of the [19]20s gave way to the uncertainties of the [19]30s and [19]40s, his subjects increasingly became uncommunicative figures, often alone in empty rooms. He translated their small dramas into something timeless and universal, in images of stillness and solitude that suggest—but never describe—a narrative. Hopper’s work engaged our imaginations by drawing on what was universal in the American experience. They capture silent moments, like frozen frames, from the drama of American life.

Talk Back

Please note that High Noon is currently on loan to the Fondation Beyeler for its exhibition Edward Hopper.

Unsolved Mysteries

At first glance, it may not look like much is going on in this painting, but if you look at it longer it may appear more mysterious. What questions does this painting make you want to ask? If you cannot answer them, does this make the painting any more or less meaningful for you?