Albert Bierstadt

Scene in Yosemite Valley

(1830 - 1902)

American 1864-1874 Oil on canvas 20 7/8 x 29 inches (53 x 73.7 cm) Frame: 28 1/2 x 36 1/2 x 3 7/8 inches Museum purchase with funds provided by the Daniel Blau Endowment Fund 1976.58

Looking West

Is the sun rising or setting? This painting, though small, captures the expansive and pristine quality of the American landscape at a time of westward expansion, a sign of hope for the progress to come, but also a memorial for the innocence lost.

A Day in the Life

Land of the Free

As the United States grew westward in the 1800s large areas of wilderness were explored and, in many cases, developed for human use. How did landscape painters, such as Albert Bierstadt, contribute to the ways Americans thought about their relationship to the land and each other? Are these ideas still relevant today? Explore these questions with Linda S. Ferber, Art Historian and Curator at the New-York Historical Society, in the following video from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Nature and American Vision: The Hudson River School from LACMA on Vimeo.

Transcript:

American landscape painting acquired an extraordinary resonance in the nineteenth century. Recognizable American scenery, but conceived on the models that had long been established in European painting that signified, particularly, two basic responses. There was the wilderness, which evoked the sublime—excitement, agitation, wonder. And then, the beautiful, which signals a landscape that has been cultivated by the hand of man to be a hospitable setting. In a way, they’re clichés, but there’s a lot of truth in them when you begin to unpack them.

By the 1830s the wilderness was rapidly being claimed, cultured, cultivated, developed. And there’s always this push and pull in the American psyche between a belief in progress and a reverence for the sanctity of the so-called wilderness. But landscapes tell stories; they tell it through weather, through the time of day. Can you walk into the painting easily, or are you obstructed—would you have to sort of clear the way? And one of the great iconographies that shows the hand of man beginning to operate is an ax-cut stump. It’s unmistakable and it’s what I call a memento mori—this is what was forfeited in order that you could have this vista. There is a beauty and a harmony and finish to these paintings that makes them very attractive, but it just takes a couple of visual cues to initiate a deeper understanding of the moment in the historical mindset.

One of the reasons, I think also, that landscape was seen as so powerful in the United States is that it implies a collective ownership. It’s like [Thomas] Cole’s admonition: whether it’s the banks of Hudson or the banks of the Oregon, this is your country. Looking at these landscapes it conceives of Americans as a unified set of political understandings; it conferred upon what was in fact a very contentious and fragile union of interests—it implied that it was a nation. It is, sort of, the great song “This Land is Your Land, This Land is My Land”; it’s sung visually, in a way, in these paintings. But some of the complexities, some of the tensions, and some of the darker sides of this kind of movement are still acknowledged here and there. These paintings are, to be sure, they are an ideal vision, but they’re very convincing and they reflect a set of beliefs that are still current today.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

The deer is easy to see in this painting, but did you know there is also a fox? The deer is the prey animal, the animal that is being hunted. The hidden fox is the predator, or the animal that hunts other animals.

A predator’s eyes face forward to better track and hunt prey. Try looking at this painting like a predator might by cupping your hands and placing them on the sides of your forehead. What details do you notice when looking this way?

Now try viewing the painting like prey animals by folding your hands and placing them over your nose. How does the prey animal see different than the predator animal? Like the deer, prey animal’s eyes are located on the side of the head, allowing them better peripheral or side vision to see any approaching predators from the side or from behind.

Signs & Symbols

Golden Light

Look closer at how the light appears in this painting, a deep gold that infuses the surrounding environment. At the time this was painted, gold had recently been discovered in California and the nation was recovering from years of civil war.

Poll

What do you think the golden light might mean?

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

American and Chinese Landscapes

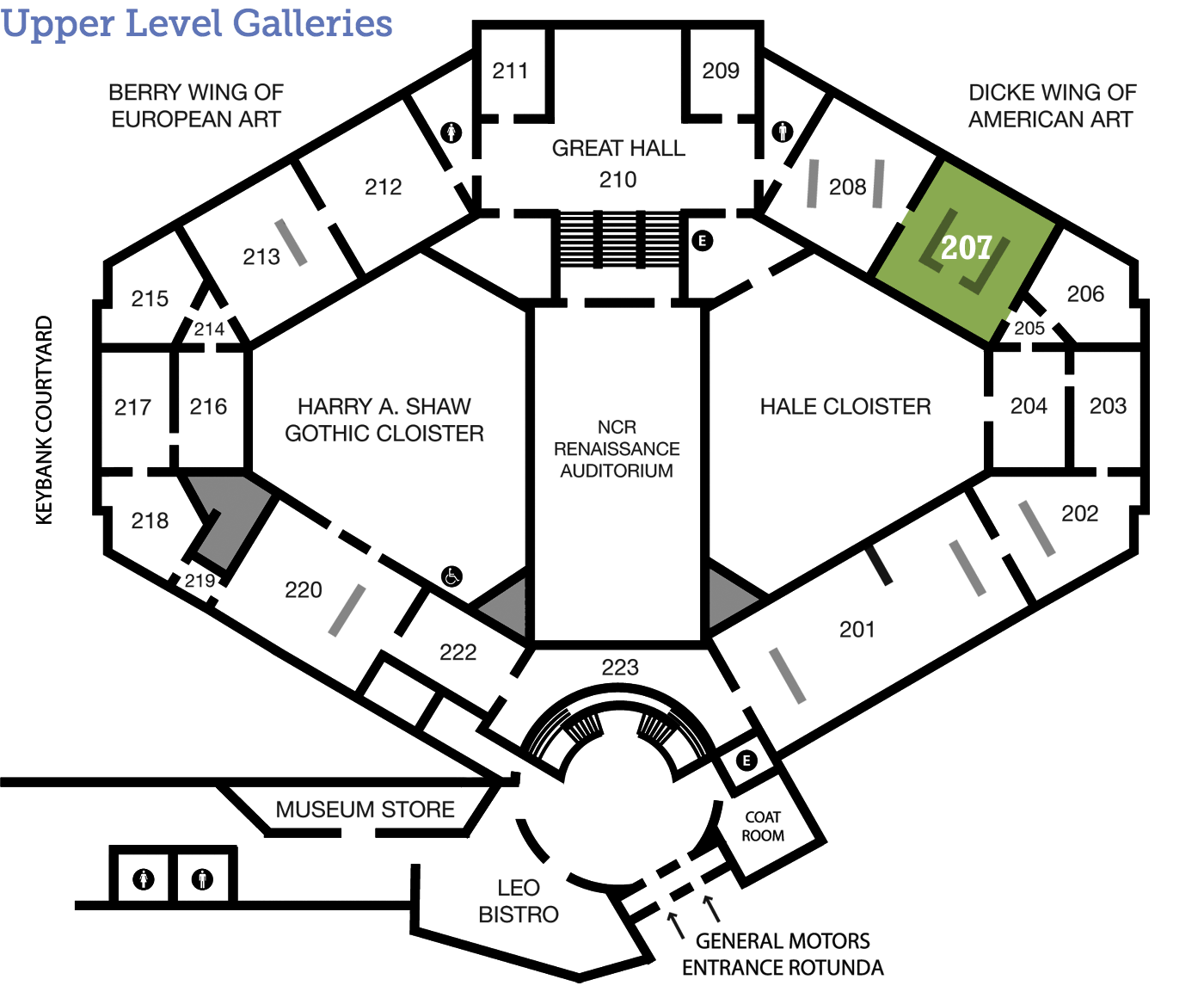

The American landscape was a popular subject for painters in the 1800s. Across the Pacific Ocean, Chinese painters were also very interested in landscapes and had been for a long time. Compare Scene in Yosemite Valley with Landscape of Tianxin Mountains by Kuncan in Gallery 112 downstairs. Both paintings evoke the meditative quality of nature with contrasting hills and valleys and a misty atmosphere. However, there are many differences, such as the perspective. Scene in Yosemite Valley, like many other European and American paintings, has a distinct horizon line and changing shades on the hills, giving an impression of depth that recedes into the distance. In contrast, Landscape of Tianxin Mountains has no fixed horizon and consistent shading, encouraging your eye to wander back and forth in a variety of paths. Look for other similarities and differences and consider how these compare with your own experience of seeing nature.

Kuncan (Chinese, 1612–1673), Landscape of Tianxin Mountains, dated 1663 or 1664, ink and color on paper, 41 5/8 x 11 1/8 inches. Gift of Mrs. Virginia Kettering, 1976.277

About the Artist

Go West, Young Man

Albert Bierstadt moved to the United States from Germany with his family when he was young, and he was adventurous throughout his life. He lived in New York, but he is best known for his large-scale paintings inspired by western landscapes. In 1859, Bierstadt traveled as far as the Rocky Mountains. In 1863, he went to California with the writer Fitz Hugh Ludlow and saw Yosemite Valley for the first time; he would return again in 1871. How did he work in these rugged conditions? Find out more from Alex Nyerges, Director and CEO of The DAI from 1992–2006, in the following audio clip.

Transcript:

Bierstadt was clearly the most popular and probably the most famous of all the painters at mid-century, doing these rather dramatic paintings. Bierstadt was schooled in Dusseldorf and because of his interest in the dramatic light and contrast of the Dusseldorf school at mid-century, his approach usually was very different—much bolder colors, sharper mountains, deeper crevices—but this is much more peaceful. And you'll find this softer side to Bierstadt often in sketches that he made when he was traveling. Bierstadt traveled—it was rather rugged travel. Yosemite was still virgin wilderness largely unseen by people from anywhere other than Native Americans. He would have taken with him a limited amount of canvas board, sketch pads, and then paints. He was trying to capture the essence of what he saw. He would return to his studio in New York and from that create a larger picture. The saga that Bierstadt was attempting to tell was that of a vanishing wilderness. In this picture, you can even see the sun setting on an era that people saw coming to a close. In 1863 or 1864, when this picture probably was painted, America was torn by civil war, and the West represented the only salvation and peace that one could find in the country.

Talk Back

Changing Viewpoints

Visual media often play an important role in shaping public opinion, and even sometimes public policy. In 1864 President Abraham Lincoln granted Yosemite Valley to the state of California as a park, perhaps in part due to the awe-inspiring paintings and photographs of the region by artists such as Bierstadt. These in turn encouraged tourism to such places, and expanded the ways Americans thought about the land they inhabited. As you look at Scene from Yosemite Valley today, how does it compare with your vision of what America is, or can be?