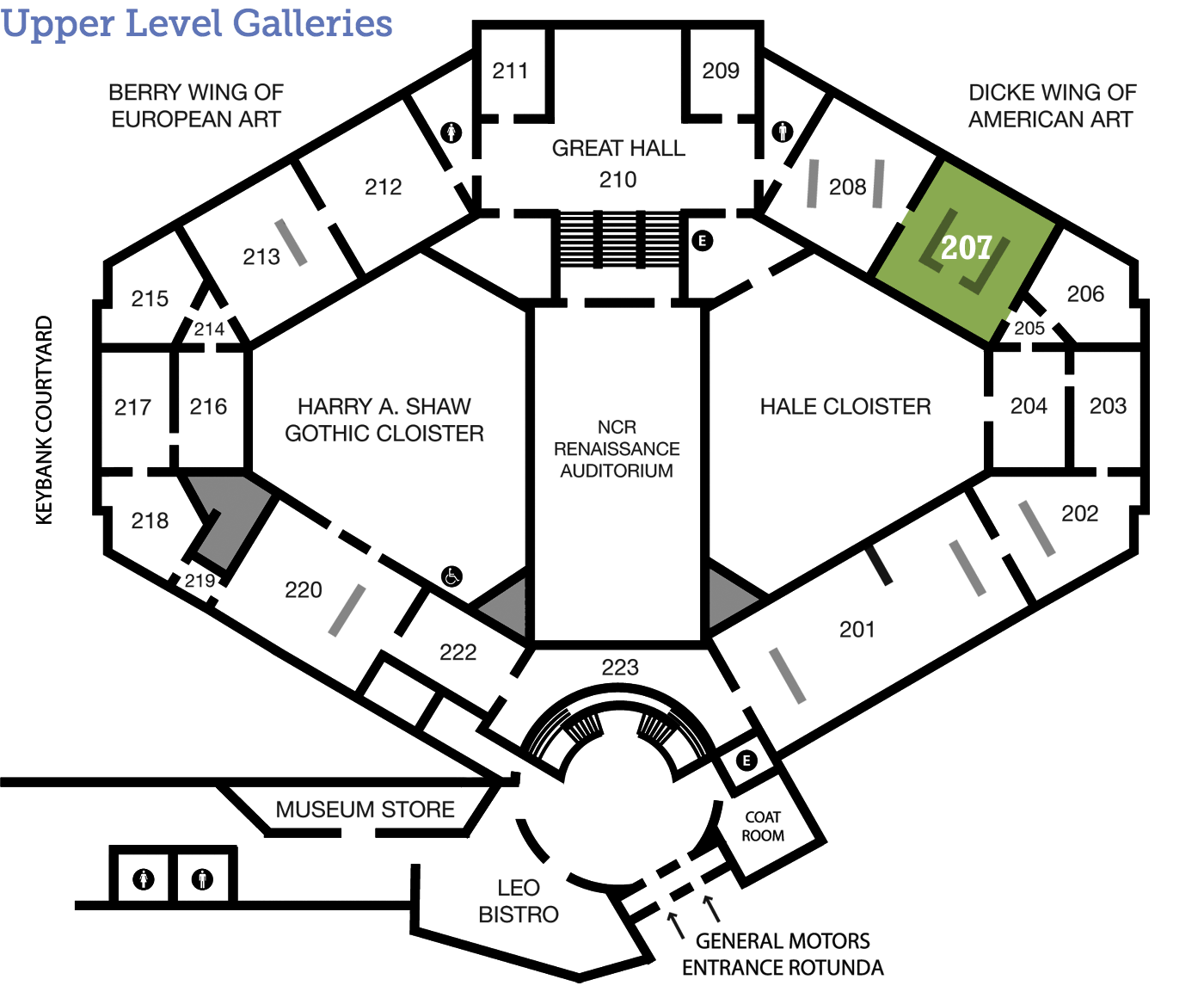

Robert S. Duncanson

Mayan Ruins, Yucatan

(1821–1872)

American 1848 Oil on canvas 14 x 20 inches Purchased with funds provided by the Daniel Blau Endowment 1984.105 207

The First African-American Painter to Achieve International Fame

The Cincinnatian Robert S. Duncanson went from painting houses to dining with Lords and Ladies, including the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who praised his work. How did he accomplish this? This small, early painting by Duncanson opens a window onto the pioneering artist and his work.

A Day in the Life

A First for Dayton

Robert S. Duncanson was the first African-American painter to achieve international success. In the 1860s—during the peak of the Civil War—he traveled to Canada, Ireland, Scotland, and England, where he was appreciated as a leading landscape artist. His masterpiece Land of the Lotus Eaters (1861), based on a poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, was even praised by the poet himself.

Another first for the African-American community took place in Dayton in 1949. The first Ohio chapter of The Links, Inc.—a professional organization of women dedicated to enriching the cultural life of African Americans and other persons of African ancestry—was founded in Dayton on May 28, 1949. Learn more about the work of the organization from Sharon Howard, a current member of the Dayton chapter, in this video.

Transcript:

The Links, Incorporated, is an international, not-for-profit organization that was established in 1946. The original intent of our members was to bring together African-American women who were influential in their communities, who wanted to do good work, and provide outreach in the communities in which they lived. The Dayton chapter was chartered in 1949, so we are one of the oldest chapters. We build our platform on key initiatives, like health and human services, the arts, education, financial literacy, all centered around helping to improve our communities.

Over the years, The Links has had a tremendous partnership with The Dayton Art Institute. We value this iconic museum in our community and what it can do to help enlighten the lives of our young people within the communities in which we serve. So, this is a tremendous opportunity for us. It is great that The Dayton Art Institute is willing to work with us. Our young, African-American students who may never have had the opportunity to walk into this museum now do, thanks to the Dayton chapter of The Links, Incorporated.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

Originally from Cincinnati, Ohio, Robert Duncanson traveled the world and painted the different landscapes he saw along the way.

Imagine you are with Robert Duncanson traveling through Mexico. Draw the things you might encounter during this trip and around the ruins. What types of plants and animals will you see?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Travel Guide Without the Travel

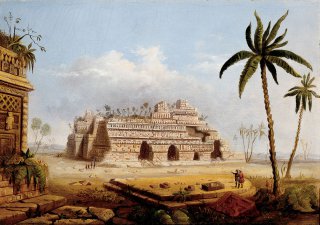

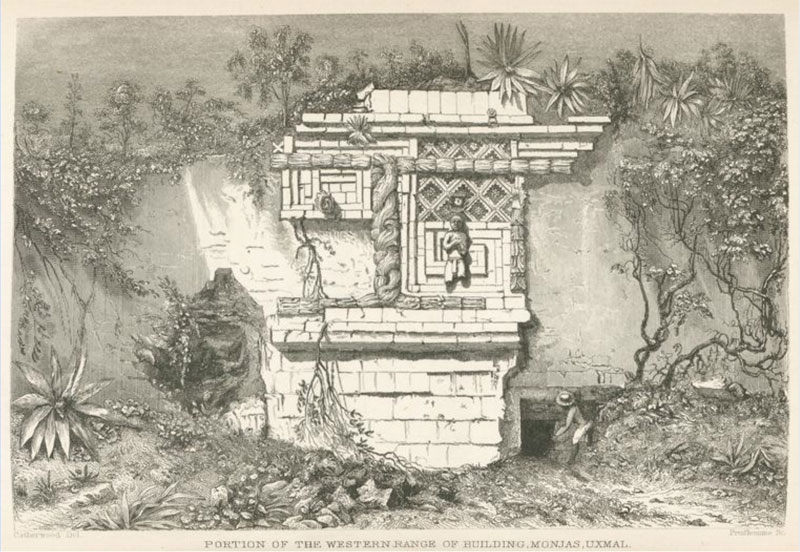

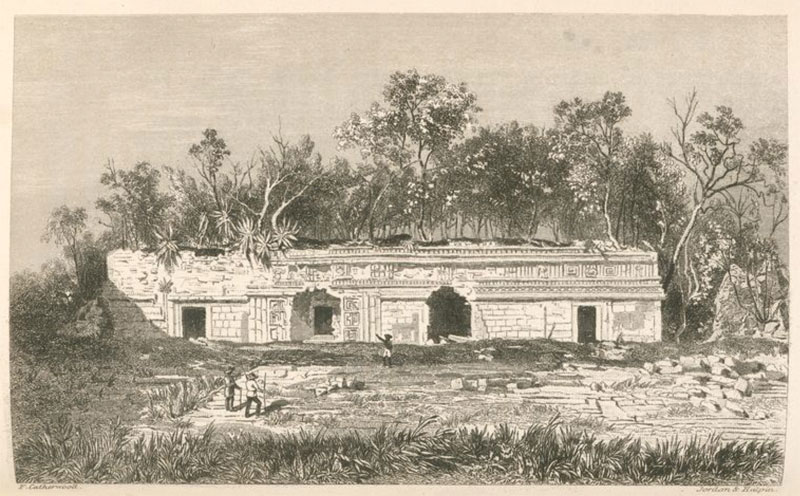

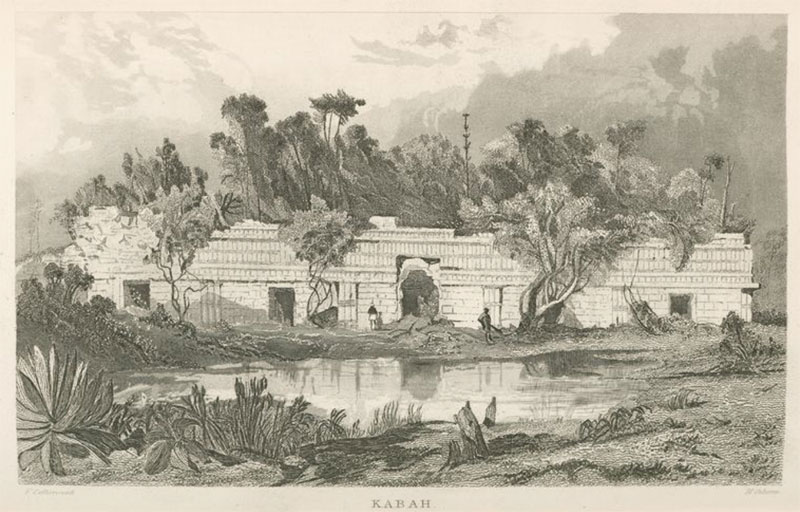

This painting depicts Mayan ruins in the Yucatan peninsula, but Duncanson never visited the region, which was not that unusual. Before the invention and widespread use of photography many artists would paint scenes of other lands based on information brought back by explorers and other travelers. During Duncanson’s time the remains of the Mayan civilization were being rediscovered and enchanted the public imagination, particularly through the best-selling book Incidents of Travel in the Yucatan (1843) written by John Stevens with engravings by Frederick Catherwood. Duncanson could use such reports as material for his own imaginative creations. Indeed, many elements of Mayan Ruins, Yucatan resemble parts of Catherwood’s engravings, such as those illustrated below. Look closer for similarities between the two, but also consider how Duncanson’s vision is different.

Fredrick Catherwood, Portion of the Western Range of Building, Monjas, Uxmal, 1843, etching. Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library, “Entwined serpents over a doorway,” New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed July 8, 2015, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-121d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (artwork in public domain; photograph provided by the Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library).

Fredrick Catherwood, Chunhuhu, 1843, etching. Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library, “Building at Chunhuhu. [Chunhuhub],” New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed July 8, 2015, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-c25d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (artwork in public domain; photograph provided by the Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library).

Fredrick Catherwood, Kabah, 1843, etching. Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library, “Building (Casa No.3),” New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed July 8, 2015, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-11db-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (artwork in public domain; photograph provided by the Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library).

Further reading: Joseph D. Ketner II, The Emergence of the African-American Artist: Robert S. Duncanson 1821-1872 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1993), pp. 24–25.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Discovering Duncanson

Who was Robert S. Duncanson and how did he become one of Cincinnati’s prized painters before going on to acclaim in Canada, Ireland, and England? Duncanson scholar Joseph D. Ketner II, presently the Henry and Lois Foster Chair in Contemporary Art Theory and Practice and Distinguished Curator-in-Residence at Emerson College, shared some information about the artist with The Dayton Art Institute. Click on the questions below to see his answers.

What was Duncanson’s African-American heritage?

Joseph D. Ketner II:

Robert Duncanson’s life unfolded in a scenario typical for a mixed-race "free colored person" in antebellum America. His parents John Dean and Lucy, along with his grandparents, moved north to Fayette, New York from their native Virginia around the turn of the nineteenth century. The United States Census lists them as "mulatto" "free colored persons," who worked as carpenters. The Duncanson clan probably benefited from the first mass emancipation of slaves after the American Revolution. The majority of those liberated came from the Upper South (states such as Virginia) and were mixed-race slaves, who as offspring of the master often held privileged positions in the slave hierarchy, were taught skills, and were educated. Many of these former slaves moved north, seeking opportunity in northern states that had abolished slavery by 1803, in the first massive migration of African Americans to the North. The Duncansons followed this migratory pattern and, in fact, moved into the Central New York Military Tract, where the Federal government located and granted land to Revolutionary War veterans, implying that Duncanson’s grandfather, Charles (c. 1744–1828), may have earned his freedom in exchange for military service.

Duncanson moved to Cincinnati in 1841, aspiring to become an artist. What brought him to this point?

Joseph D. Ketner II:

The Duncanson family participated in the growth of the black middle class at the turn of the nineteenth century, a time when African-American artisans predominated in the trades in the United States. Robert Duncanson was mentored in the family trades of carpentry and house painting. In Monroe, Michigan, at the age of sixteen, Robert reached the apprentice stage of his training and his father hired him out to a local house painter. From this craftsman Robert would have learned painting, glazing, mixing colors, preparing surfaces, and applying paint. Sufficiently trained in these skills, Duncanson went into business with a partner in 1838. Duncanson was in business for only about a year before the partnership dissolved, and he resolved to become an artist and to break into the art community, which was almost exclusively Caucasian. An abolitionist journal of the period reported that a friend, perhaps his former partner John Gamblin, encouraged him to paint a portrait, provided the supplies, and thus stimulated Duncanson’s artistic ambitions. With encouragement, he moved in 1841 to Cincinnati.

What made Cincinnati such an attractive place for an African-American artist at this time? Were there any challenges?

Joseph D. Ketner II:

Since the introduction of the steamboat in the 1820s, Cincinnati grew from a frontier outpost to a booming economic center that boasted a distinctive regional culture. In the 1840s and 1850s Cincinnati experienced a tremendous economic boom. Art thrives with patronage and with the newfound prosperity Cincinnati was able to offer education, exhibitions, and patrons. Situated at the nexus of the north-south and east-west axes, Cincinnati was also a stronghold of both the pro-slavery and the anti-slavery movements. Although slavery was illegal, the city also had close social and economic ties to the southern states. The economic prosperity of the city attracted a large number of free people of color and over the decade became one of the larger concentrations of that population in the US. Despite the pervasive existence of racial discrimination, the city’s complex, and at times paradoxical, social and cultural dynamics contributed to the development of a thriving African-American community.

At the time Duncanson moved to Cincinnati in 1841, the city experienced a series of pro-slavery riots, among the most severe in the nation. Living in neighboring Mt. Healthy with family friends, Duncanson observed the active Cincinnati cultural community and taught himself to paint by copying prints, sketching from nature, and painting portraits. Like many artists of this period, economic pressure forced him to become itinerant, traveling across Ohio and Michigan seeking portrait commissions. It was extremely difficult for an African American in an era of “Black Laws” to secure commissions. However, the violence of the riots galvanized the anti-slavery activists, who forced the state to repeal its “Black Laws” in 1849, providing free blacks legal protection similar to that accorded to whites, and offering educational opportunities with state-sponsored education. Allowed to flourish, the result was the growth of a black middle class—overwhelmingly mixed-race—formed of clerks, shopkeepers, barbers, businessmen, and artists.

How did Duncanson’s work mature in Cincinnati?

Joseph D. Ketner II:

Duncanson participated in the national fascination with landscape painting and used the North American landscape as a metaphor to express America’s cultural identity. Duncanson followed the model of landscape painting established by the east coast painters Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. The catalytic moment for Duncanson was in 1847 when Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life came to Cincinnati. The purchase and subsequent public exhibition of these paintings in Cincinnati at the Western Art Union in 1848 exerted a profound impact on the developing art community of Cincinnati. Prior to the appearance of The Voyage of Life Duncanson had been an itinerant painter producing portraits, still life, basically whatever was commissioned or would sell. The visceral experience of seeing Cole’s paintings in the flesh—the rich color, exquisite detail, and moralizing anecdote of Cole’s didactic series—transformed his artistic practice. Upon seeing The Voyage of Life he immediately changed his style and began to concentrate on painting landscapes, clearly emulating Cole’s style.

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848), The Voyage of Life: Childhood, 1842, oil on canvas, 52 7/8 x 76 7/8 inches. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Alisa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.16.1 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by the National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution).

In the early 1850s Duncanson made remarkable artistic progress from an itinerant painter to being regarded by Cincinnati’s civic leaders as “one of our most promising painters.” The success of these ambitious commissions from abolitionist sympathizers earned the artist sponsorship to take the traditional artistic pilgrimage across Europe. After completing the monumental Belmont Murals for Nicholas Longworth’s grand home “Belmont” (now The Taft Museum of Art), he embarked on his “grand tour” of Europe with friend and colleague William Sonntag. [Museum Note: An example of Sonntag’s work in The Dayton Art Institute’s collection is Dream of Italy, in the same gallery as Mayan Ruins, Yucatan, Gallery 207.]

William Louis Sonntag (American, 1822–1900), Dream of Italy, 1859, oil on canvas. Museum purchase with funds provided by Mrs. R. Warren White, the Daniel Blau Endowment Fund, the William Henry Zweisher Educational Trust Fund of The Dayton Art Institute, and Donald G. Schweller in honor of Mary Schweller by exchange, 2004.29.

What did Cincinnati look like during Duncanson’s time? In the same gallery, Edward Beyer’s View of Cincinnati from 1853 gives us a detailed, bird’s-eye-view.

Edward Beyer (German, 1820-1865), View of Cincinnati, 1853, oil on canvas, 35 ½ x 72 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family, 1999.89.

Drawn from Joseph D. Ketner II, Robert S. Duncanson: “The Spiritual Striving of the Freedmen’s Sons,” Exhibition Catalogue. Catskill, NY: Thomas Cole House, 2011, pp. 5-7 and “Thomas Cole, Robert Duncanson and Ohio River Valley Landscape Painting,” unpublished lecture, Taft Museum, Cincinnati, (2014). For more on Ketner’s Duncanson research visit http://www.josephketner.com/robert-s-duncanson/.

Look Around

See It in Person!

Duncanson’s painting of Mayan Ruins represents Mayan culture filtered through travel books and Duncanson’s imagination. How do these compare with actual Mayan objects? Visit Gallery 102 to see some examples, such as this Mayan Vessel with Three Figures and Glyphs.

Maya, Vessel with Three Figures and Glyphs, 600–800 CE, terracotta and pigments, height 7 ¼ inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Honorable Jefferson Patterson and Mr. and Mrs. Richard N. Grant, Jr., 1973.3.

About the Artist

Talk Back

Telling the Truth

Although it is based on the reports of travelers, Mayan Ruins, Yucatan is mostly an imaginative rendering of a distant place. Duncanson would go on to achieve fame for landscape paintings based on his own travels in the Ohio River Valley, Canada, and Europe. How important is it for a painting to be based on direct observation by the artist? What does it mean for a painting to be truthful to reality?