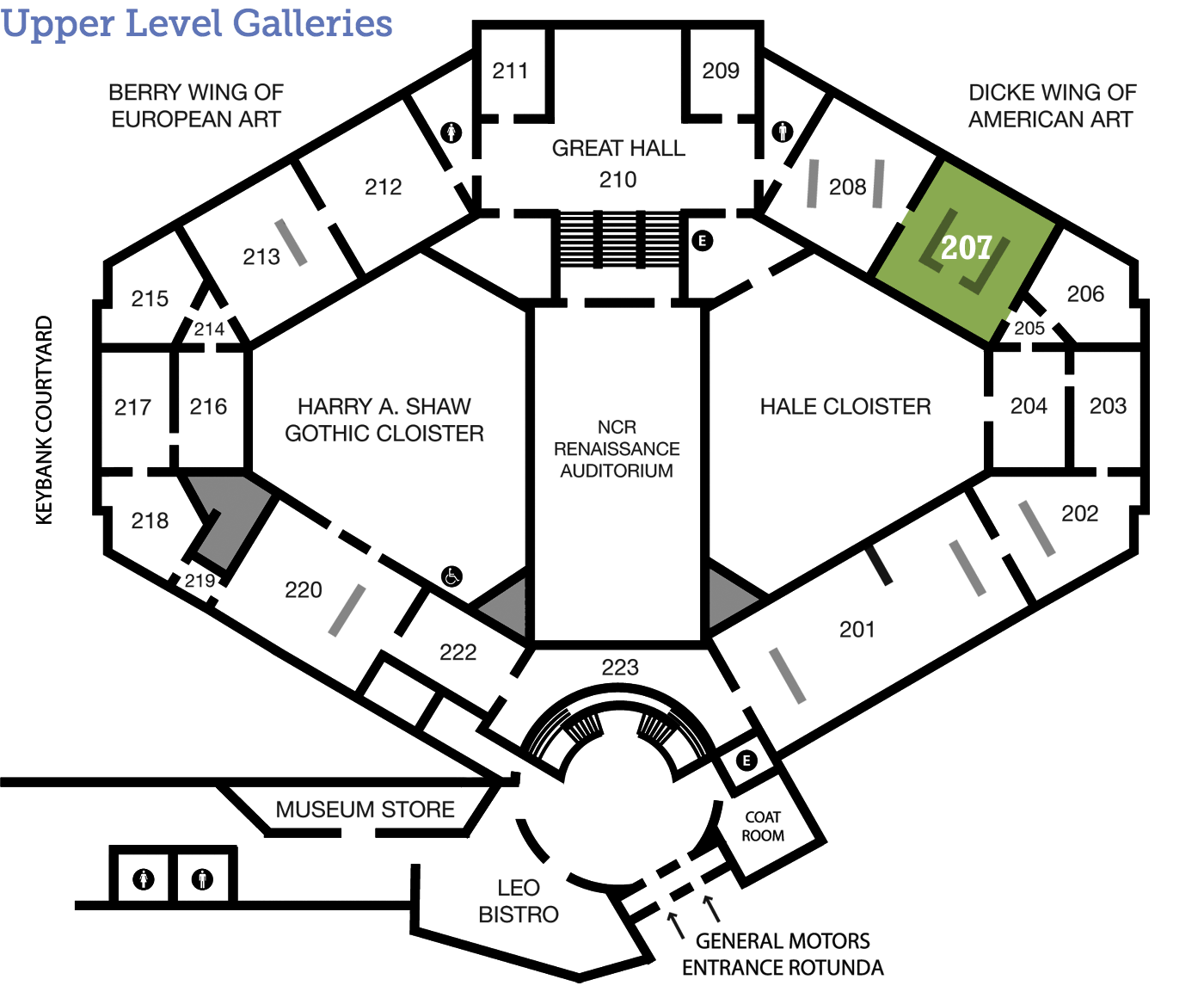

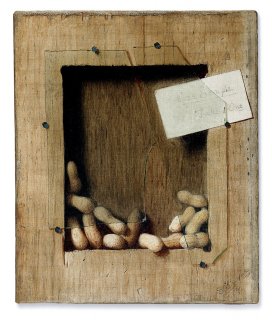

De Scott Evans

Free Sample, Take One

(1847-1898)

American 1891 Oil on canvas 12¼ x 10 in. Museum purchase with funds provided by the 1985 Associate Board 1984.108 207

This Story is Nuts!

What do a trick of the eye, a secret identity, and American art have in common? The answer is this painting by De Scott Evans! Explore the tabs below to learn about the mystery that surrounds this work of art and the artist who created it!

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Trompe l’Oeil

Trompe l’oeil: A French term literally meaning “trick the eye.” Sometimes called illusionism, it's a style of painting which gives the appearance of three-dimensional, or photographic realism. It flourished from the Renaissance period (14th-17th centuries) onward. The development of linear perspective in 15th-century Italy and advancements in the science of optics in the 17th-century Netherlands enabled artists to render objects and spaces with eye-fooling exactitude. Both playful and intellectually serious, trompel’oeil artists toy with spectators' optical senses, raising questions about the nature of art and perception.

Text adapted from ArtLex. “Trompe l’oeil.” Accessed 16 July 2014.

http://www.artlex.com/ArtLex/t/trompeloeil.html

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

A Secret Identity?

Transcript:

Free Sample, Take One is signed “S. S. David.” So how can we know for sure that it’s by De Scott Evans? The short answer is…we can’t!

During his lifetime, De Scott Evans was known as a painter of Victorian genre scenes—often depicting beautiful ladies engaged in leisure activities such as playing the lute or performing dramatic readings. But did he have a secret pastime painting trompe l’oeil images? The evidence says he did.

Although only three trompe l’oeil paintings are signed with Evans’s name, dozens of similar compositions are signed with variations of the pseudonym you see here; Stanley Scott David, Stanley S. David, S. S. David, Stanley David, Scott David, and simply David are all found on various canvases depicting subjects with related themes. Some are so similar to the paintings signed by Evans that their attribution to the artist seems obvious. One Evans trompe l’oeil, Hatchet on Wood, is undeniably similar to one signed by Stanley S. David, entitled Washington’s Hatchet—in fact, in many ways it’s almost identical!

Based on the research of many professionals, scholars have accepted that De Scott Evans and Stanley Scott David are one and the same. Evans probably used the pseudonym because trompe l’oeil received criticism in the art community in the 19th century for being “low-brow” art. Ironically, even though during his lifetime he sought to be valued as a painter of Victorian sensibilities, De Scott Evans’s trompe l’oeil works are now coveted thanks, in part, to the mystery surrounding them.

Just for Kids

Look!

Were you fooled by this painting? De Scott Evans painted Free Sample, Take One to trick your eye. Does looking at this painting make you want to reach out and grab a peanut? How is looking at this painting online different from looking at it in the museum? Which one is more believable?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

I Spy

John Frederick Peto was very well known in his lifetime as a talented and prolific painter of trompe l’oeil style paintings. (For more on tromp l'oeil see "Tools & Techniques".)

John Frederick Peto, (1854-1907), Mug, Book, Smoking Materials, and Crackers, c. 1880-1890. Museum purchase with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Floyd L. Rietveld, the NCR Corporation, the Monsanto Research Corporation and the 1986 Associate Board Art Ball, 1986.59.

Do you think other still life works in this gallery are considered trompe l’oeil? What is the difference between the two genres of painting?

Whereas both create the illusion of three-dimensionality, trompe l’oeil tries to trick the eye into believing that the flat canvas plane actually shows depth of space. Traditional still life paintings are painted in order to look “real,” but aren’t concerned with fooling the viewer to the extent of a trompe l’oeil painting. Trompe l’oeil seeks to go one step further and trick the eye into believing that it sees three-dimensional objects, not a flat surface.

About the Artist

Talk Back

What is a Masterpiece?

De Scott Evans deliberately used a pseudonym for his trompe l’oeil and wanted to be remembered for his genre scenes. Does this change whether you would consider Free Sample, Take One a “masterpiece?” Why or why not?