Helen Frankenthaler

Sea Change

(1928–2011)

American 1982 Acrylic on unprimed canvas 38 x 116 ½ inches Museum purchase with funds provided by the 1987 and 1988 Associate Board Art Ball 1987.53

Transformative

Like Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler experimented by working with the canvas on the ground and applying paint in unique ways, such as staining, creating a complex interaction of surface and depth. Look closer at this protean painting and it may change the way you see it.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

It Leaves a Stain

Look closer at the surface of this painting. Does it look transparent, as if you can see through the paint to the canvas underneath? This is because Frankenthaler used a painting technique known as staining. Paint is thinned down and applied to raw canvas, and the paint soaks into the fibers and stains them. See how paint is prepared for this technique in the following video from the Museum of Modern Art, along with a photo of Frankenthaler in action.

© 2010 The Museum of Modern Art

Transcript:

A stain is made when you take a paint and you thin it out with a lot of solvent; in the case of oil painting, a lot of turpentine. So the paint becomes very very watery, becomes very dilute, the color is reduced, and also because it is so watery, that stain can penetrate into the canvas itself. In the work of Rothko we know that he layered stain over stain over stain, so we’re quite literally seeing through these very very thin washes, if you will, of paint.

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Try it!

Helen Frankenthaler experimented with paint. She developed a new way to paint called staining. She thinned down thick paint to a watery liquid.

Using markers, create a design or pattern on a coffee filter. When you have finished with your design take a spray bottle and lightly spray the coffee filter. How did your design change after you sprayed the water? Did your colors soak and spread onto the coffee filter?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Changes

What are the different details and textures you can see in this painting? How do they reflect the changes in Frankenthaler’s work at this time in the 1980s? Take a closer look and learn more in the following video with Carol Nathanson and Lisa Morrisette, art historians formerly associated with Wright State University.

Transcript:

Carol: I’m Carol Nathanson

Lisa: And I’m Lisa Morrisette

Carol: And we’re art historians associated with Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Lisa: And we’re here today at The Dayton Art Institute to talk about the Helen Frankenthaler [painting] Sea Change. Helen Frankenthaler recently passed away December 27th of 2011. When I was reading her obituary in The New York Times, they had mentioned that she had an interest in art from a very young age as a child when she used to dribble nail polish into a basin of water to watch the color flow, and I think that’s a really interesting idea as we sit here and look at the flow of color in Sea Change.

Carol: Absolutely, there are just so many wonderful passages of color and tone into each other, and areas where vivid color seems to rise to the surface.

Lisa: Yes, and I particularly love the way that not only do we see this staining of the surface, but then the juxtaposition of these bold passages of color that really rise to the surface.

Carol: One interesting transitional point that I see here is a kind of rosy area, a kind of rosy cloud off to the right that then is given a much more emphatic expression in that bit of red close to the right hand edge.

Lisa: Yes, and that bit of red is then picked up almost diagonally, just slightly off center in the brighter hot red and then in that warm pink splash at the bottom corner, so it sort of pulls your eye all the way across this canvas. So technically, then Helen Frankenthaler is considered a second-generation artist?

Carol: Yes, she is, despite those intimate connections with the first generation, most intimate of which may be her marriage to Robert Motherwell.

Lisa: Also, my understanding was that the technique that she developed of soaking—or staining and soaking—the canvas was one in which she was pouring, which was a technique related to Jackson Pollock.

Carol: Absolutely. The thing about Pollock and his influence is that Pollock actually did do staining, but his use of staining was never central to the appearance of his paintings. The stained elements—he worked on raw canvas—and the stained part of his compositions exists at the very lowest level and he layered paint over it. I think with Frankenthaler you have someone who gives staining a really important role; that’s why her work looks so revolutionary and why she's often described as having discovered the process of staining.

Lisa: I see, I didn’t realize that. Here, the stain is very much the predominant, but she also comes back with this very thick opaque color, this gold, like meteorite showers across the canvas.

Carol: Let’s talk a little bit about that (and by the way, she is using metallic paint there). Frankenthaler began to apply paint thickly above the stained layer in the early 1980s, which is the date of The DAI’s painting, and what I find interesting is that not everybody approved of what she was doing. She was so associated with staining and large color fields that this seemed to be a kind of cop-out or a betrayal. What I’d like to ask you, because I think you might have some interesting ideas about this, is whether dealers and collectors, and perhaps certain critics, try to lock an artist into a signature style, disregarding the fact that artists feel the need to experiment and grow and try different procedures.

Lisa: Well, I think that’s very much the case. For a gallery dealer it’s a commercial venture and they want a package and something that’s recognizable, and it seems to me that whenever artists dramatically deviate from what they are known for, that it’s not what people expect and they’re sort of not comfortable—is it authentic?—instead of seeing that growth.

Carol: Good point. Well, I need to add here that when Frankenthaler first began adding those raised passages in the early 1980s, she was uncertain of what she was doing; and she even talks about the fact that perhaps she shouldn’t be doing this, perhaps she should be working in those passages to surrounding areas. Then she says—and this is interesting—she says that she found she couldn’t do that because the painting dictated to her that that was what it wanted to be. To me that sounds very Abstract Expressionist—working intuitively, looking at a painting as if it has a life of its own. You know, we like to think of Abstract Expressionist work as being very spontaneous, intuitive, and of course Frankenthaler’s art, to some extent, was. And yet, there is something that’s almost studied about this composition; the repetitions, the balances, they’re all there.

Lisa: Exactly. This is a marvelous composition in the fact that a composition is a structured design and really holds your vision together.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Push and Pull

How might an artist view this painting? American artist Sam Gilliam draws inspiration from Helen Frankenthaler for his own work. Hear his thoughts about Sea Change in the audio clip below, and then compare this with a work by Gilliam in The DAI’s collection, 3 Point (not currently on view).

Transcript:

I really think that this is such a truly great painting. Its graphic sense; its planar sense in terms of the way that the color establishes the planes. I like Frankenthaler because she endures as a painter. The horizontalness of the painting endures. She is a stain painter, she works with sponge; and that she achieves these levels of what is called push and pull, near and distant spatial aspects, whether it's light to heavy. When the painting seems to be very, very easy, it's so hard to do.

Sam Gilliam (American, b. 1933), 3 Point, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 118 x 296 inches. Museum purchase, 1987.57

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Thick and Thin

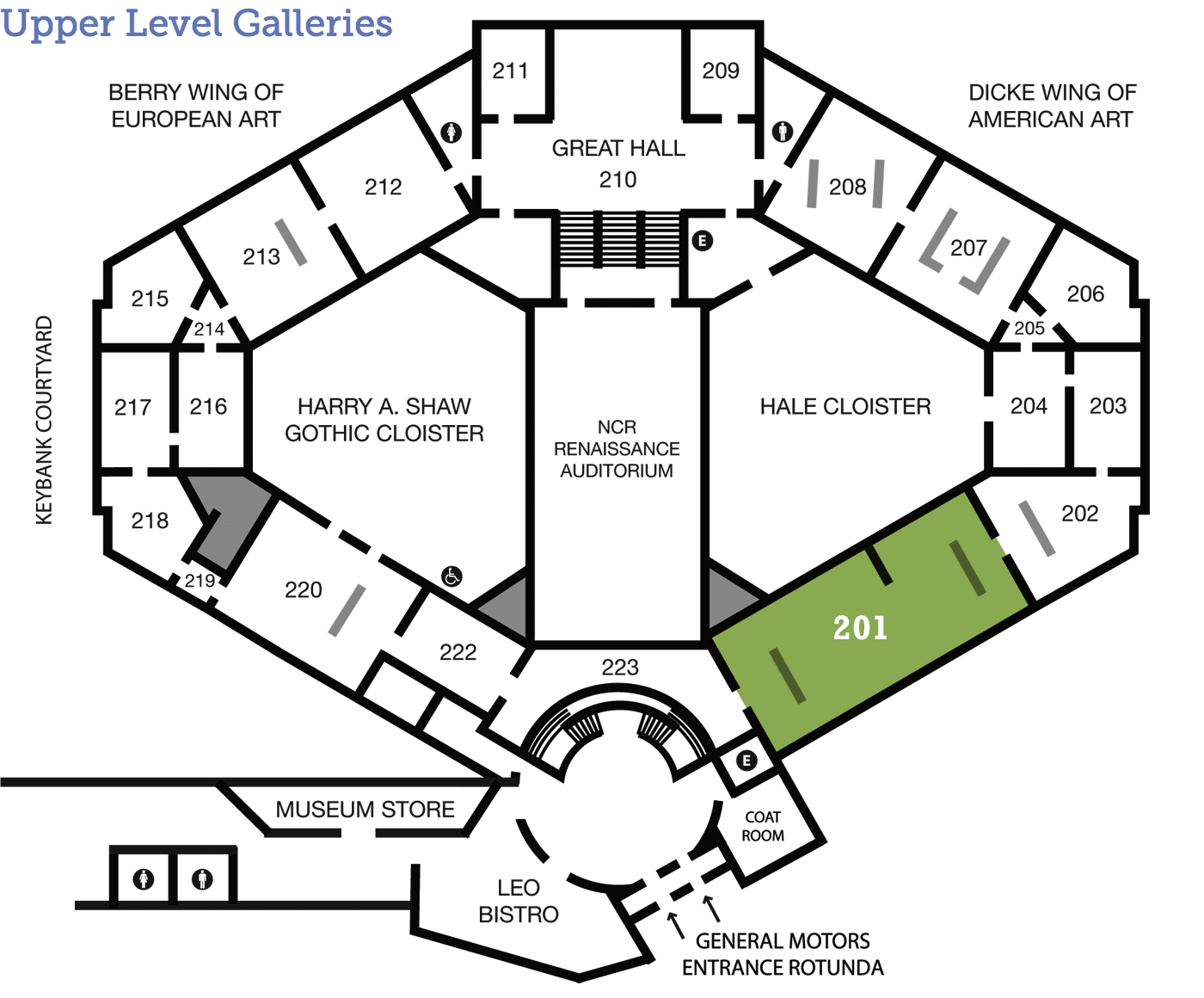

Frankenthaler was influenced by New York artists from the mid-1900s that are often referred to as “Abstract Expressionists.” These painters explored the expressive qualities of paint by using gestural brushstrokes or broad fields of color. You can see examples of these painters, such as Mark Rothko, Norman Lewis, Hans Hofmann, and Robert Motherwell, in Gallery 202. (Frankenthaler studied with Hofmann and was married to Motherwell.)

Joan Mitchell, whose painting Untitled hangs adjacent to Frankenthaler’s Sea Change in Gallery 201, was also influenced by Abstract Expressionist painters. Look closer at both and see how they treat the texture of paint and the canvas itself. Both use a combination of extremely thin and thick paints, but consider how similar or dissimilar the visual effects are.

Joan Mitchell (American, 1925–1992), Untitled, c.1961, oil on canvas, 76 ½ x 51 inches. Gift of Mr. Max Pincus in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Elton F. MacDonald, 1964.25.

About the Artist

Talk Back

Echoes of Shakespeare

The phrase “sea change” refers to a profound transformation, and it was first used in this way by William Shakespeare in his play The Tempest (1610–1611). It appears in a song by the spirit Ariel, who sings to Ferdinand about the physical transformation of his father who died in a shipwreck.

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Hark! now I hear them,—ding-dong, bell.

We cannot be certain that Frankenthaler was directly citing this play, but she was well-read in literature. Also, the painter Jackson Pollock, who influenced Frankenthaler, made a painting entitled Full Fathom Five in 1947 (you can see an image of this painting at the Museum of Modern Art here). So, Frankenthaler could be contrasting her work to Pollock’s, as well as connecting with Shakespeare’s poem. In what ways can you see the poem echoed in Frankenthaler’s painting? What kind of “sea change” might the painting refer to?