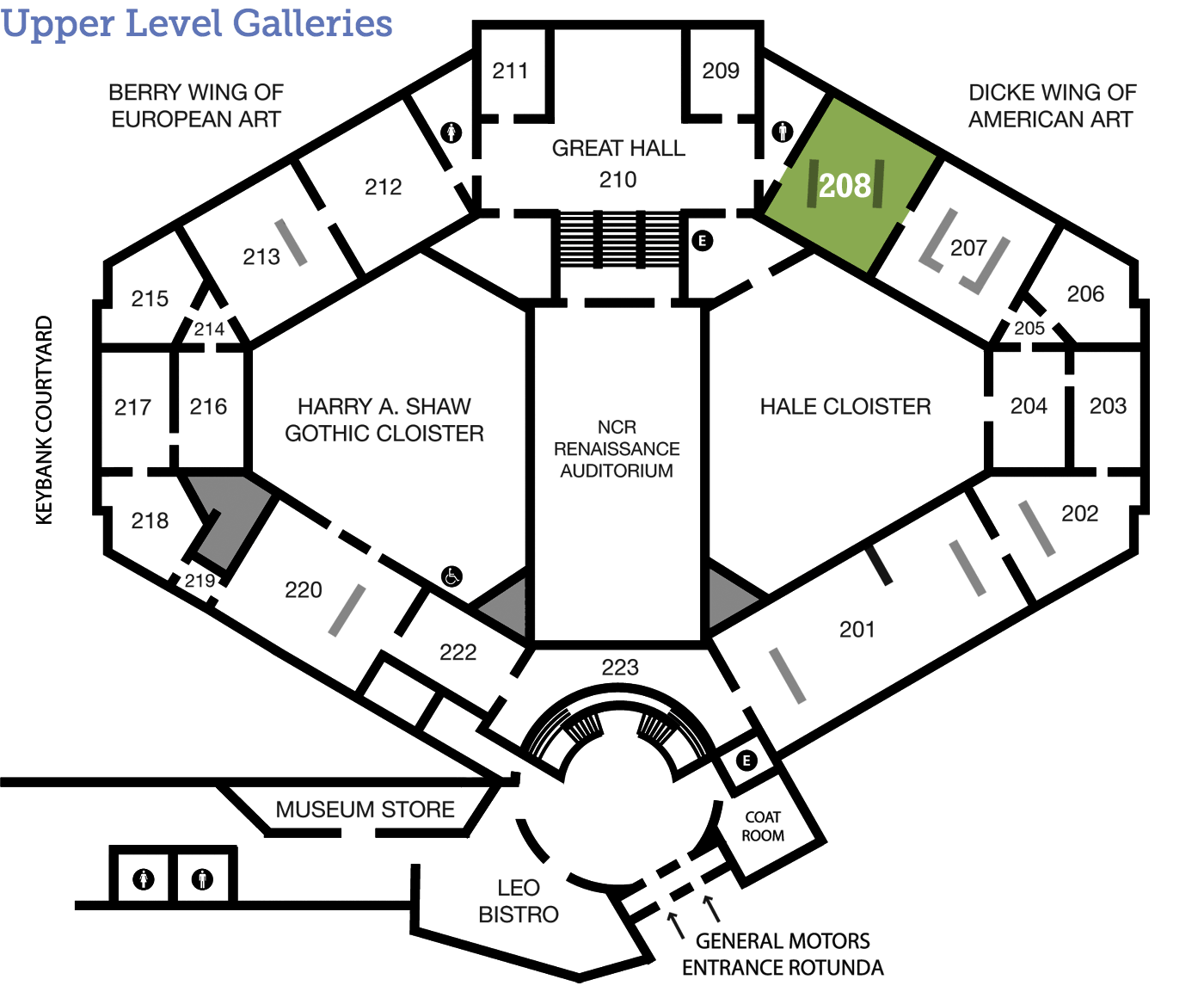

Gilbert Stuart

Mrs. Michael Keppele (Catherine Caldwell)

(1755–1828)

American c. 1800 Oil on canvas 28 3/8 x 24 3/8 inches, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William A. Siebenthaler 1991.163

More than Meets the Eye

Do you judge by appearances? Do you often change your opinion after learning more about someone? Get to know this portrait by Gilbert Stuart and challenge how you think about the images we present to each other.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

A Change of Clothes

There is more to this painting than first meets the eye. In 1824, Mrs. Keppele received a makeover thanks to an amateur artist. The story was reported by one of her grandchildren:

A friend of my grandmother borrowed it in order that a young artist might be benefited by its study. It was removed for that purpose to his studio. Shortly afterward the family were asked if they knew that the artist had removed a great part of the picture, and upon going for it they found that he had painted out all but the face and hands. When Sully was asked to replace the portion removed, he at first refused to touch anything which had been done by Stuart; but upon reflection, and seeing that the portrait was ruined as it stood, relented, and agreed to do so.

“Sully” is the painter Thomas Sully, who at this time was already one of America’s most popular portrait painters. That Sully did the job is confirmed in his own “Register” where he recorded his painting projects; he was paid $30 for it.

Quoted in George Champlin Mason, The Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1879), p. 210. Thank you to William Keyse Rudolf at the San Antonio Museum of Art for the additional information on Thomas Sully.

Just for Kids

Imagine!

Who was Mrs. Michael Keppele? Catherine lived in Philadelphia and was married to the mayor, Michael. When Gilbert Stuart painted Catherine, he also painted a portrait of her husband. The painting of Michael is now lost. What do you think he looked like? How do you think he was dressed?

If you had to assign an Emoji to Catherine, which one would it be? Recreate that Emoji’s face. There are lots of portraits in the museum. Look around at the people. Are their emotions all the same? What Emoji would you assign to the other portraits?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

All by Myself

This painting of Mrs. Michael Keppele was originally one of a pair with her husband, Mr. Michael Keppele, as was usually the case in portraits of couples in the 18th century. Gilbert Stuart painted many couples’ portraits in the burgeoning cities of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. Traditionally, portraits were painted on certain occasions, such as a marriage, the birth of a child, a rise in family stature, or in memoriam for the departed. When these were painted, the Keppeles, residents of Philadelphia, had been married for about fifteen years. In 1811, Michael became the mayor of Philadelphia. So, at this point we are unable to connect this portrait to any known event in their lives.

Now, Catherine sits alone. Over time, paired portraits are often separated through inheritance or family dissent and then sold to different parties. Does seeing her in isolation change your encounter with her? Is the painting incomplete without its partner?

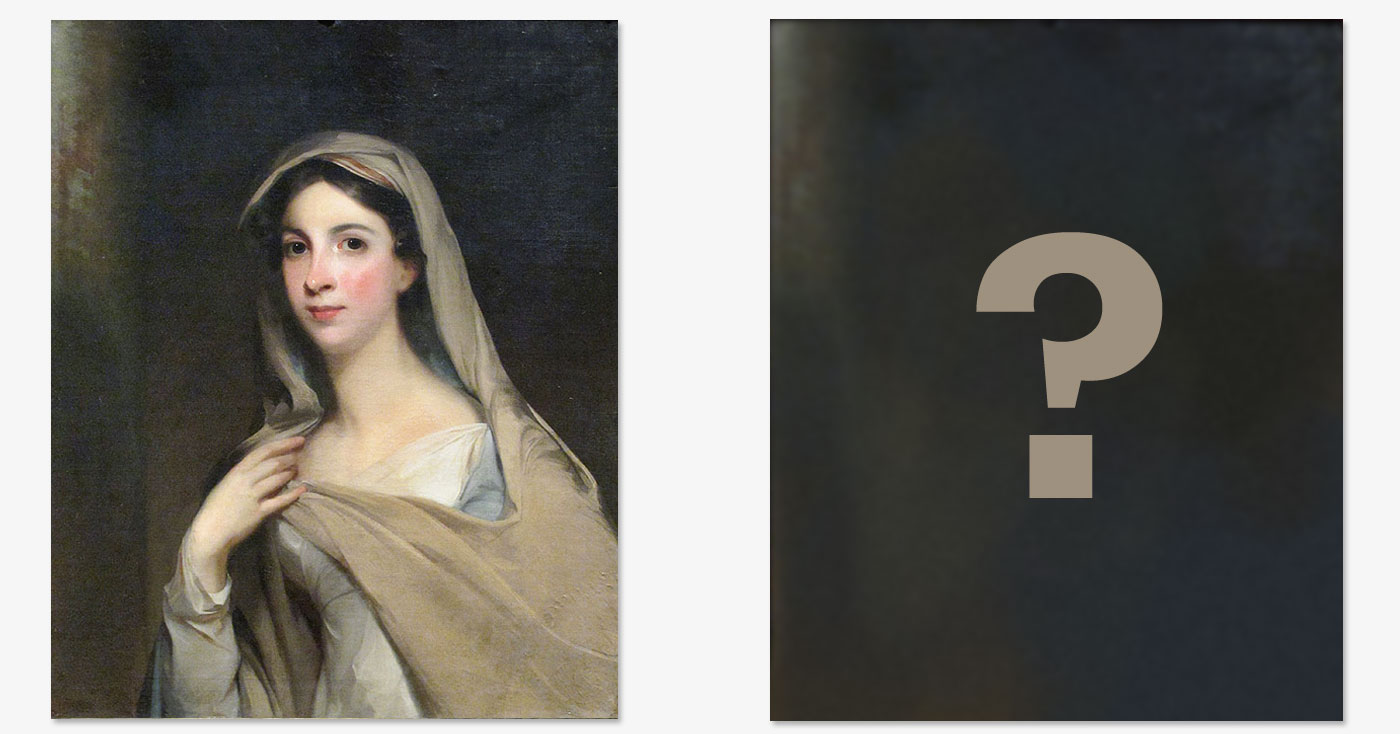

To get an idea of what a complete pair would look like, look at Gilbert Stuart’s portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Anthony, Jr. These were also painted during Stuart’s time in Philadelphia. Note the compositional similarities that connect the pair, such as the angles of the sitters, the format of the portraits, and the backdrops.

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828), Mrs. Joseph Anthony, Jr. and Joseph Anthony, Jr., c. 1795–1798, oil on canvas, 30 x 23 3/8 and 30 x 24 ½ inches (each). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1905, 05.40.2 and 05.40.1 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org).

An example of a complete pair at The Dayton Art Institute is John Wollaston’s portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Philip de Visme, located in the same gallery as Mrs. Michael Keppele, Gallery 208.

John Wollaston (American, born England, active 1742–1775), Mrs. Philip de Visme (Anna Proro Stillwell) and Philip de Visme, 1749–1752, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches (each). Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family, 2000.55 and 2000.54.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Have I Seen You Somewhere Before?

Due to an experiment in learning Stuart’s methodology, the portrait of Mrs. Keppele was scraped down by an amateur, and the drapery was repainted by the prolific American portrait painter Thomas Sully in 1824. (See “Look Closer”.) There is a complete work by Sully in this gallery, his Portrait of Elias Jonathan Dayton. If you are in the galleries, look closer at both paintings and see what similarities you can observe in the brushstrokes, lines, and shading.

Thomas Sully (American, 1783–1872), Portrait of Elias Jonathan Dayton, 1813, oil on canvas, 35 ¼ x 28 ½ inches. Museum purchase with funds from Spencer-Dayton Family, 1944.87.1.

About the Artist

On the Nose

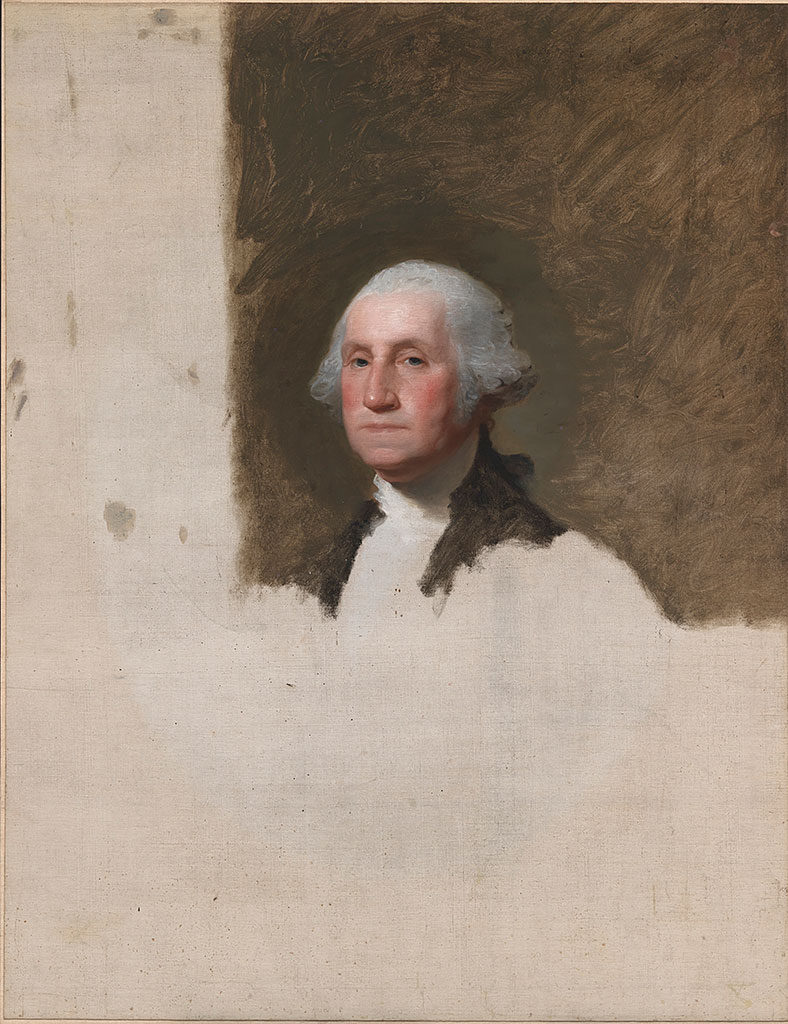

Gilbert Stuart was one of America’s most astute portrait painters. Most famous for his painting of George Washington that is the model for his likeness on the one-dollar bill, Stuart was highly sought after to make portraits of wealthy members of the new United States of America. His ability to adjust his style for each sitter resulted in lively representations that convey the personality of the individual.

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828), George Washington, the Athenaeum Portrait, 1796, oil on canvas, 48 x 37 inches. Jointly owned by The National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.80.115) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1980.1), William Francis Warden Fund, John H. and Ernestine A. Payne Fund, Commonwealth Cultural Preservation Trust (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by The National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution).

How did Stuart capture the unique person in paint? Stuart thought two facial features were vital for expressing likeness and character: the nose and brow. This idea of reading a person’s character based on her or his facial features was a popular pseudo-science during the late 18th century, known as physiognomy. An engraving based on one of Stuart’s portraits of George Washington was even used as in illustration in the English translation of Johann Caspar Lavater’s influential book Essays on Physiognomy, Designed to Promote the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind (1798). Lavater’s lengthy book discusses the various character traits communicated by different parts of the face. For example, Lavater expressed that the longer a person’s forehead “the more destitute is the mind of energy,” while the shorter a forehead is “the more concentrated, firm, and solid is the character.” Lavater praised George Washington’s forehead, noting that “it denotes uncommon luminousness of intellect.” (To learn more about physiognomy and see some examples of images used to support it, click here.)

Look closer at Stuart’s own nose and forehead in the self-portrait below. What sort of character do you think he had?

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828), Portrait of the Artist, c. 1786, oil on canvas, 10 5/8 x 8 7/8 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1926, 26.16 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org).

See William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, v. 1 (New York: G.P. Scott and Co., 1834), p. 218, Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), pp. 136–140, and Johann Caspar Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy, translated by Henry Hunter, volume 3/2 (London: Printed for John Murray, H. Hunter, and T. Halloway, 1789–1798), pp. 275–276 and 436.

Talk Back

Nobody is Perfect

This painting has been through a lot. It is separate from its companion portrait and has been retouched by another artist. How do these facts affect the way you view it? When looking at a painting, how important is it to know its history?