Chinese

Watchtower

Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE) Earthenware with green glaze 44 1/2 x 13 1/2 x 16 inches Museum purchase in memory of Kathleen (Kit) Johnston and in recognition of the many DAI volunteers she epitomized 1992.18

You Can Take It with You!

Where do you go when you die? What might you need to keep you safe and happy? This tower would have accompanied an important member of the Han society in his or her tomb, providing comfort and protection in the afterlife.

A Day in the Life

Packing for a Long Trip

Ancient bronzes, human sacrifice, and miniature people? Take a walk through the Chinese galleries with art historian Lisa Morrisette as she explores the vibrant world of funerary art, including this tower.

Transcript summary:

During the Shang and Zhou dynasties (c. 1600–256 BCE) bronze vessels were used to venerate ancestors and also buried with the deceased. Two of these objects in The DAI’s collection are the jue and the gu. There were changes to burial practice during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and into the Tang dynasty (618–906); the practice of including real human sacrifices was replaced by using small-scale clay replicas. However, there was still a continuity of spiritual belief. The afterlife was seen as an extension of the worldly life. When a person died the soul separated into two parts: the hun, which traveled to another realm of existence, and the po, the body that remained in the tomb and still needed all the comforts of daily life. So, small-scale models of things from daily life—such as servants, entertainers, animals, and buildings—were made in wood, lacquer, or clay, like this watchtower. These things were known as mingqi (ming-chee), literally “spirit utensils,” and thousands were made for tombs. While they were made through a mold process there is a real sense of animation, which we can see in many objects nearby, from the tiny people on the watchtower to the Tang dynasty figures, such as the kneeling camel or dancing women. That is the nature of mingqi; they really represent the things that one would have been familiar with in the worldly life, making the spirit comfortable in the afterlife.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

3-D Snapshots

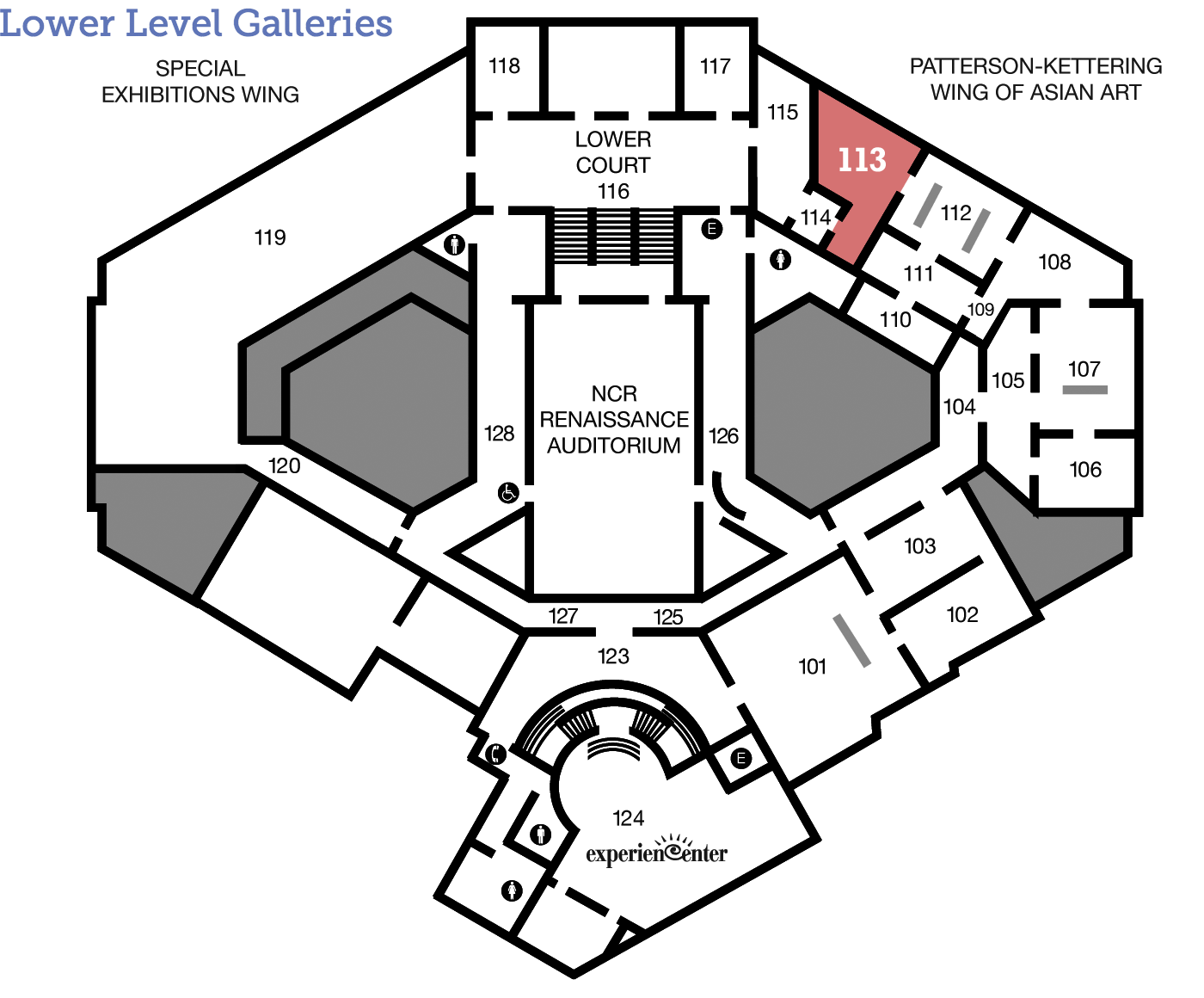

Different kinds of towers, as well as other buildings, have been found in Han dynasty-era tombs. These provide information about the architecture of the time as well as snapshots of daily life. Compare The DAI’s watchtower with the example below from the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It is built over a pond with soldiers standing guard with crossbows, a weapon perfected by the Han that contributed to their power. What other differences can you find?

Unknown Artist, China, Military Watchtower, 1st century, low-fired earthenware with green glaze, 13 x 11 ½ x 11 ½ inches. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of funds from the Asian Art Council, 98.69a,b (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, https://new.artsmia.org/).

Just for Kids

Imagine!

At first look, you may guess this is an ancient Chinese doll house. However, buildings like this have been found in tombs of noble people during the Han dynasty. Why do you think miniature buildings would have been placed in Chinese tombs?

Signs & Symbols

A Tower Fit for the Dead

Objects like this tower were small models—based on real-life buildings, people, and things—that would accompany the deceased to the afterlife. This tower has many details that ensure it would be as comfortable as the real thing! Tap on the different points of the image to learn more.

Dig Deeper

Ponies, Politicians, and Silk

This tower was made during the time of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), one of the great periods of Chinese history. What contributed to its success? Listen as Robert Jacobsen, former Curator of Asian Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, explains.

Transcript:

“The Han dynasty is one of the most glorious periods in Chinese history. The Chinese today—they call themselves Han Chinese—refer back to this dynasty, a Golden Age in cultural production [and] economic prosperity.

It was a period when China itself really created the bureaucratic system that was going to last down to the early part of the 20th century—based on a civil service system—and that grew out of Confucian teachings in the 6th century [BCE] and following centuries of the late Bronze Age. So, it was a consolidation of Confucian thought that sets this government on a kind of bureaucratic course that remains the standard hallmark of Chinese administration for several ensuing centuries.

The period is traditionally divided into a Western Han period—when the capital was at Chang'an, largest city in the world, wealthiest city on earth, at that time—and an Eastern Han period, which runs for approximately 200 years as well, when the capital was relocated to Luoyang.

This is a period of great expansion and trade. They had heard of the Roman Empire and they knew of its might and its wealth and its prosperity, and they wanted to trade their silk with that empire, and ultimately they do link up with various middle men in the Central Asian states—with the Roman Empire itself—and the Silk Trade begins in earnest during this era, 2nd century BC. That goes on to become the world's largest land trade corridor. It remained that until the 17th century, when ocean trade took over again.

One of the great trade items—besides silver—that the Chinese were trading their silk and some of their ceramics for during the early Han was the horse. A new kind, or a new breed, of horse was now introduced into China. It became extraordinarily popular. It was bigger, faster, stronger than the smaller horses, the kind of steppe ponies that they had been using to pull carriages and war chariots previously. This horse was one that could be mounted and used as a warhorse in combat. It could also be tethered, of course, to carriages and war chariots as well, as they had in the past. But it becomes almost a symbol of early Han and it was one of the main items that silk was traded for.

So, it was a period, just preceding Han, of great unification of the written language, weights and measures, and transportation which made trade, of course, possible to flourish. And it certainly does that during the Han.

© Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Spectacular!

What makes this tower an exceptional example of Han dynasty funerary art? Listen as Alexander Nyerges, Director and CEO of The DAI from 1992–2006, explains.

Transcript:

This is a spectacular example of a Han watchtower from the Eastern Han dynasty in the first two centuries of the first millennium. It was work that was created to accompany the dead into the after life. If you'll look closely at this work, you'll see the very elaborate tiled roof lines. To either side of the gated courtyard are the guard dog openings. And then the over-hanging roof eaves. And you can imagine the greater landscape. It was very typical to create works like this to resemble those watchtowers that did exist in reality. And they existed as a defensive or protective measure because in this time there were great fears of the Mongol hordes from the north. We call this a mortuary tower, or funerary art, because it was created to replicate the real watchtower so that...the noble person—or the person of particularly high rank—who owned this estate would be accompanied into the afterlife so that he, too, would have his defenses and protections against the Mongol hordes or others who might interfere with his enjoyment in the next world. This is one of the most complete examples you'll find anywhere and one of the larger and better examples outside of China of this particular type of tower. It has a wonderful patina that shows up the green glaze. But you also have to remember that this work was buried probably for the better part of 1800 years before it was uncovered sometime in the early part of this century.

Look Around

About the Artist

Talk Back

Preparing for Retirement

The height and complexity of this watchtower make it exceptional, but the characters peering from behind windows and doorways make it interesting. If you were using clay to create a building to keep you not only safe but entertained in the afterlife, what would it look like and who would you include?