Rockwell Kent

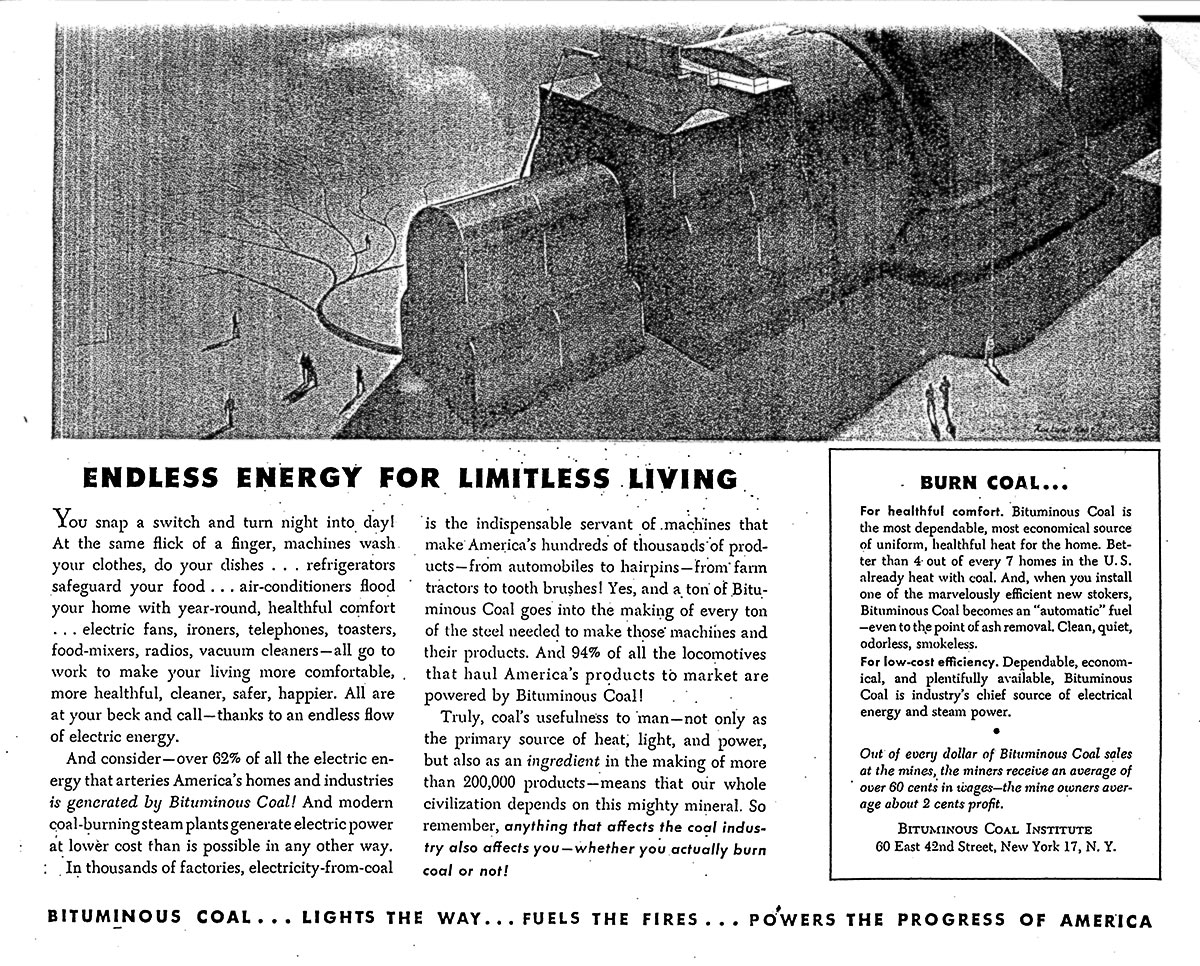

Endless Energy for Limitless Living

(1882-1971)

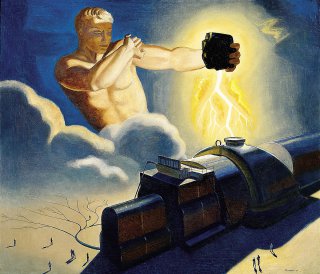

American 1945–1946 Oil on canvas 44 x 48 inches (111.8 x 121.9 cm) Gift of Dane and Kerry Dicke 1994.60

Electric

A giant strikes earthlings with lightning bolts. No, it is not a blockbuster superhero movie, but a tribute to one of America’s enduring energy sources. Exemplifying Rockwell Kent’s distinct graphic sense, this painting illuminates where art, advertising, industry, and ideology meet.

(Rights courtesy of Plattsburgh State Art Museum, State University of New York, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.)

A Day in the Life

The Art of Advertising

From 1945 to 1946 the Bituminous Coal Institute (BCI)—the public relations arm of the National Coal Association—commissioned Rockwell Kent to do a series of twelve paintings that would serve as illustrations for advertisements in popular magazines, such as The Saturday Evening Post and Newsweek (only eleven were completed). The ads highlight the benefits of coal for modern American life, from transportation and manufacturing to education and healthcare. Endless Energy, the ninth painting in the series, highlights coal as a form of energy with the massive generator in the lower right corner. All the paintings include a “Genie,” a sort of spirit of coal who dispenses its benefits on humans.

The ad agency for BCI—Benton & Bowles Inc.—sent initial sketches for each painting, Kent would develop a color sketch and then, after approval, make the painting. His correspondence with the ad agency’s Sanford Gerard shows an increasing frustration at the lack of freedom and petty criticisms he received. (Gerard initially suggested that “the faces of Notre Dame football players” might provide the best models for the coal Genie.) BCI cancelled the ad campaign in April 1946, which coincided with the beginning of the coal strike of 1946; this suggests that the ads were an attempt to strengthen the hand of the coal industry by positively reinforcing its importance in the public’s consciousness.

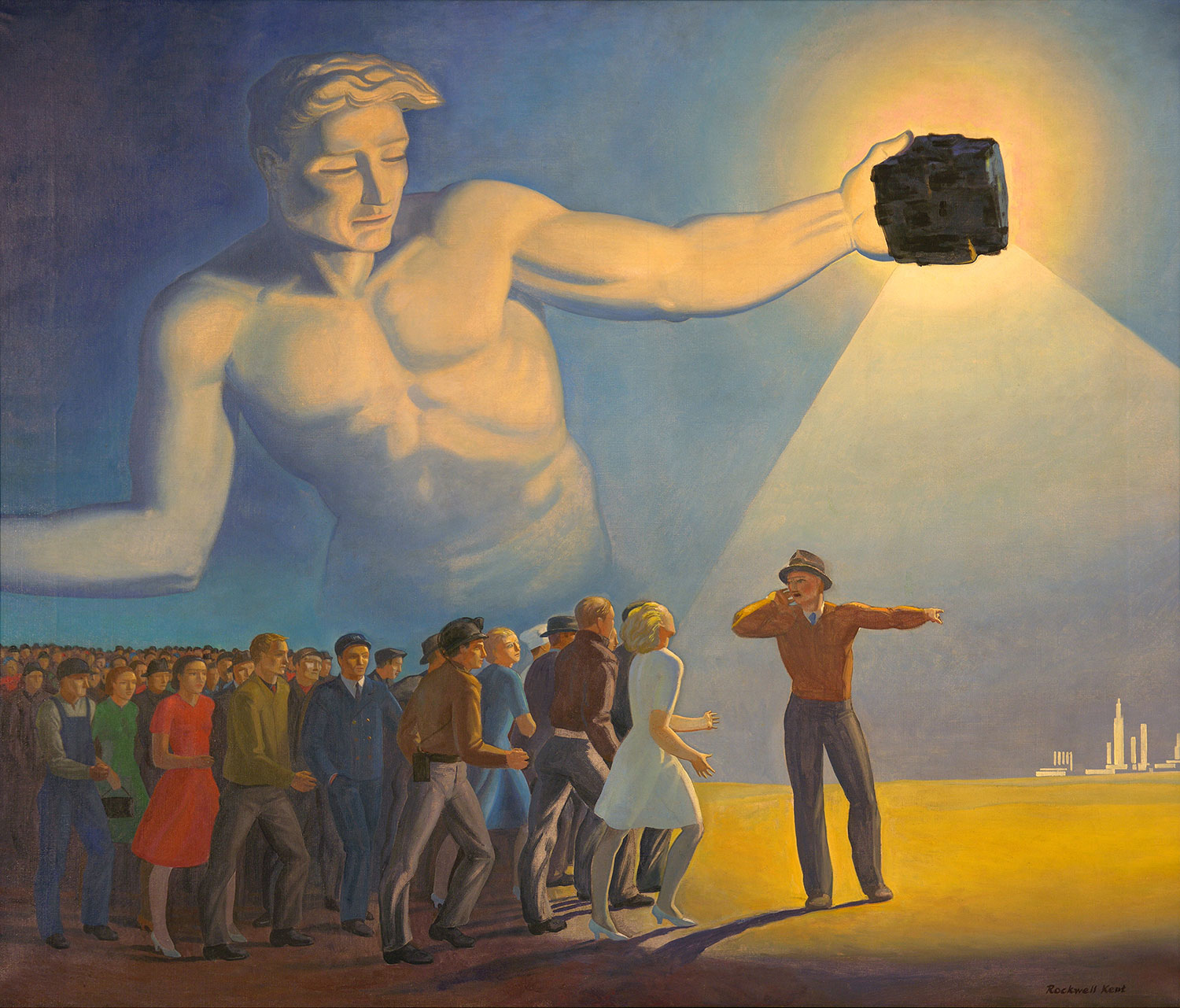

Below you can see a clip from the advertisement illustrated by Endless Energy for Limitless Living in The Saturday Evening Post from May 25, 1946, as well as an example of one other painting in the series, Generator of Jobs. Later, the BCI donated the paintings to universities that had notable mining or engineering programs, including The Ohio State University, The Pennsylvania State University, Purdue University, West Virginia University, and the University of Missouri School of Mines. Many of the paintings are still at the universities that received them; The DAI’s painting is the one given to OSU.

Rockwell Kent (1882–1971), Generator of Jobs, oil on linen, 1946. Gift of the Bituminous Coal Institute. (Photo courtesy of Purdue Galleries. Rights courtesy of Plattsburgh State Art Museum, State University of New York, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.)

Detail, Bituminous Coal Institute Advertisement, The Saturday Evening Post, May 25, 1946.

Further reading: Eric Schruers, “Interpreting the Real and the Ideal: Rockwell Kent’s Lost Bituminous Coal Series Rediscovered,” The Kent Collector 25/2 (Summer 1999): 24–34.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

Illustrious Illustrator

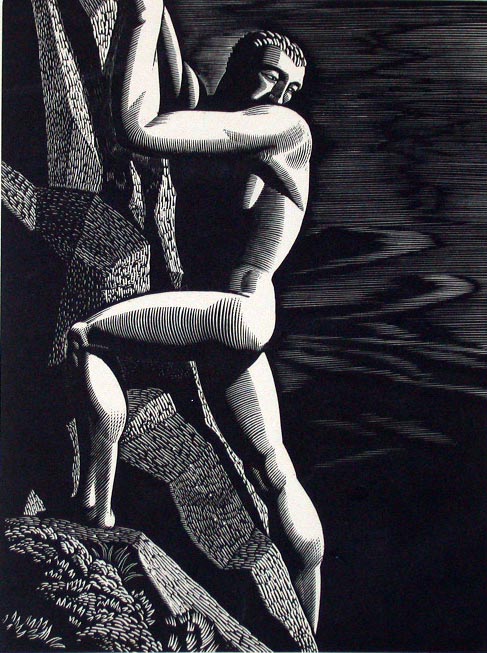

Kent is most well-known for his graphic art, especially prints and illustrations. Masterpieces include illustrations for editions of Moby Dick (1930) and Candide (1928). Kent studied architecture and always had a strong sense of line and the contrast of light and dark. An example of his prints in The DAI’s collection is Mountain Climber (not currently on view).

Rockwell Kent (1882–1971), Mountain Climber, after 1919, woodcut on paper, 7 13/16 x 5 7/8 inches. Gift of the Print Club of Cleveland, 1933.24.9. (Rights courtesy of Plattsburgh State Art Museum, State University of New York, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.)

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Dual Nature

Endless Energy for Limitless Living is somewhat unusual among Kent’s paintings, since it was commissioned for an advertisement (see “A Day in the Life”). A more typical work, Adirondack Landscape, is nearby in this gallery. Consider how these two images depict different ways of relating to nature.

A love of wild nature, especially polar regions, was central to Kent’s art and writing. From 1905–1934 he spent extended periods in Monhegan Island (Maine), Newfoundland, Alaska, Tierra del Fuego (Chile), and Greenland. He published illustrated adventure writing based on many of these trips, such as N by E (1930) and Salamina (1935) that were extremely popular.

Rockwell Kent (American, 1882–1971), Adirondack Landscape, c. 1940, oil on canvas, 34 x 44 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family, 1998.6. (Rights courtesy of Plattsburgh State Art Museum, State University of New York, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.)

Further reading: Fridolf Johnson, “Rockwell Kent, the Restless,” in “An Enkindled Eye” The Paintings of Rockwell Kent: A Retrospective Exhibition, Richard V. West (Santa Barbaba, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1985), 9–11.

About the Artist

Artist as Activist

Besides being a prolific artist, Rockwell Kent was a political activist, engaged in causes he hoped would make America a more free and just country. While Kent rarely expressed his political views in his art, his political action led to some unusual experiences.

Quiz

Which of the following do you think happened to Kent?

He testified before Senator Joe McCarthy about being a Communist.

He was a plaintiff in a Supreme Court Case.

He received the International Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union.

Talk Back

A Conflict of Interests?

Rockwell Kent was an outspoken activist for progressive causes, including workers’ rights. At the same time, he accepted a commission to make a series of advertisements for coal, ads that appeared at the same time as a massive workers' strike against the coal industry. Should an artist separate their life, including social-political beliefs, from their art? If an artist does not believe in what they are making will the art, in the end, be compromised in some way?