Norman Lewis

Prehistory

(1909–1979)

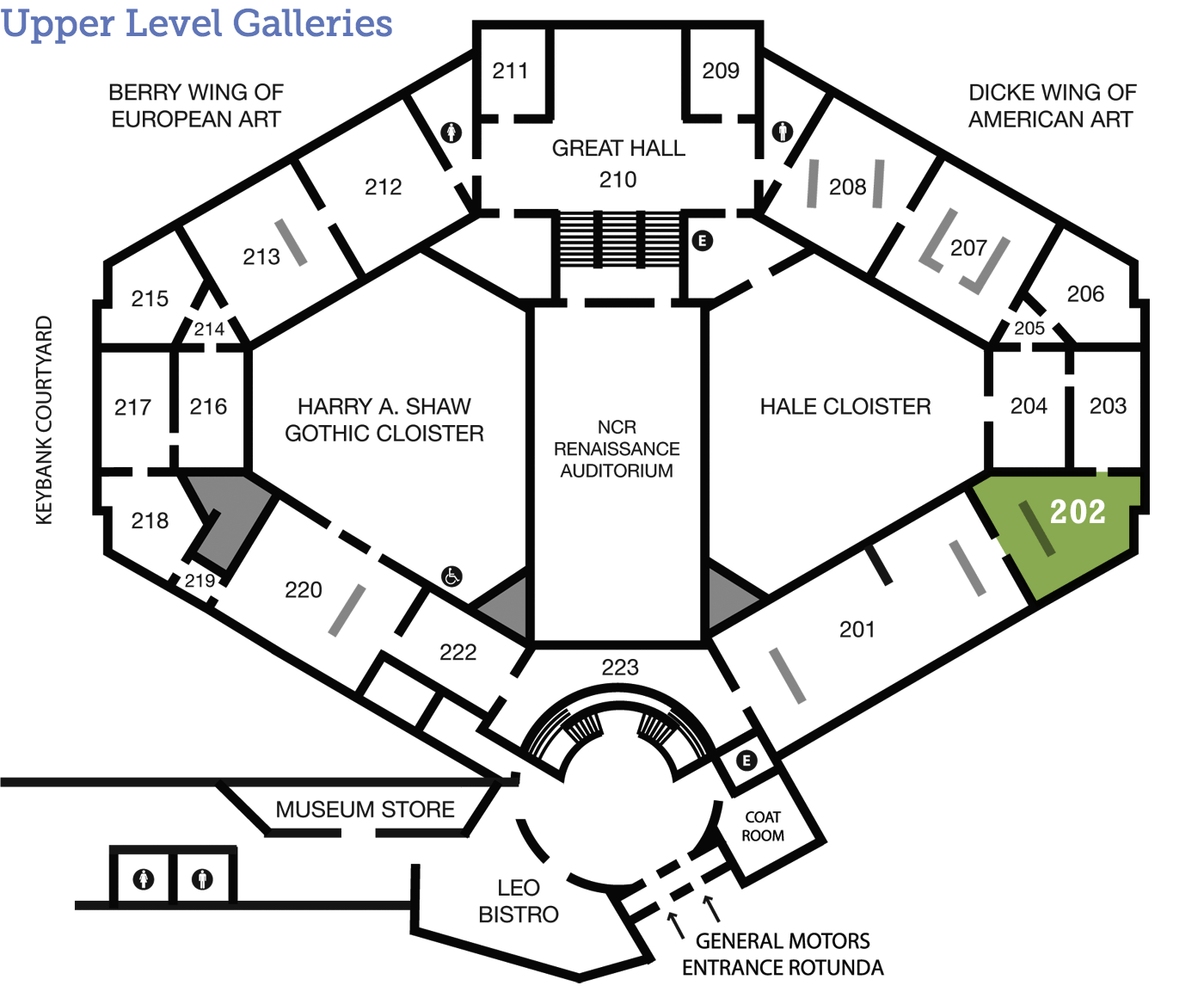

American 1952 oil on canvas 25¾ x 49¾ in. Gift of the James F. Dicke Family 1996.13 202

Improvising Infinity

How do you paint something you have never seen? What is the image of a time before time? In Prehistory Norman Lewis—one of the only African-American painters in the Abstract Expressionist movement—explores the potentialities of paint and the creative act to express the individual and touch the universal.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Can You Paint with a Dry Brush?

Look closer at Prehistory. Does the paint look different? That is because Norman Lewis used a special painting technique called “dry-brush.” Listen as the Dayton Art Institute’s Director of Engagement Jane Black talks about this unique technique.

Transcript:

“Hi, my name is Jane Black and I’m the director of engagement here at the Dayton Art Institute, and I’m going to talk to you a little bit today about the dry-brush technique. So, whenever you’re looking at a painting you’re looking at two things: you’re looking at the context and the content that the artist has chosen to depict in their composition, and that’s true of abstract work as well as narrative work or realistic paintings. You’re also looking, though, at the techniques; you’re looking at the kinds of painting that the artist chose to employ.

A dry-brush technique is in a way more similar to a sgraffito or sfumato, which are very ancient terms and ways of painting that are very subtle, and that’s the connection with them to dry-brush technique. When you look at a lot of paintings you’re looking at impasto painting and you’re looking at very wet painting techniques where you can really see the brushstrokes that the artist has created with the paint and the type of brush that they’re using and then how that relates to the support.

With dry-brush you’re looking at […] a very minimum amount of paint that is loaded onto a dry brush. So there’s very little dampness or liquid involved, and that’s true in oil paint, in acrylic paint, or in watercolor, you can use this technique in any of those. If you want to look outside of Abstract Expressionism, you might look at Richard Diebenkorn or Andrew Wyeth; they both use the dry-brush technique a great deal.

Today, though, we’re going to talk about Norman Lewis, who was one of the Abstract Expressionist painters. He was part of the New York School that developed with Rothko and Pollock, and all of the painters who were exploring really new territory after World War II. […] all through his career he did paintings that were black paintings, and I first saw his work […] as part of this exhibition that was here at the Dayton Art Institute in 1999, and one of our paintings—Cantata—was featured in that show [Norman Lewis: Black Paintings, 1946–1977]. This is the other painting in our collection, Prehistory.

When you look closely at this painting, it’s similar to a color-field painting, and you can see those in our collection as well—we have a really beautiful [Helen] Frankenthaler and a number of others. They have more wide swaths of color that are fairly consistent in tone and color. When you look at the Norman Lewis its very subtle. You’ll see these very quiet layers of different tones, of blacks and greys; in this painting this kind of rusty-red. In a color-field painting that’s done with staining technique it’s a very clean surface. In these paintings you can see these very subtle shapes that he’s created with that dry brush, by taking that very minimally loaded brush and creating that shape carefully on the last color surface that he’s laid down on the painting.

So, you might compare this to some of the other works that are in the gallery and you’ll see other painting techniques—as I said that impasto technique—or with the Rothko you see something that looks a lot like dry-brush, but you’ll have to decide for yourself whether it really qualifies.”

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

Norman Lewis was from Harlem, New York. Harlem is known for art and music. Many painters like Norman Lewis were inspired by jazz music. He would often listen to jazz music while painting. When you look at Prehistory, do the painting’s gestures remind you of jazz music? Why or why not?

If you could assign a sound to each of the paintings in this gallery, what would they be? Compare and contrast your sounds, consider how the paintings relate to the sounds.

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Prehistory in the History of Norman Lewis’s Painting

Over the span of fifty years Norman Lewis produced a body of paintings that was quite diverse, ranging from social-realism to pure abstraction. Where does Prehistory fit into this rich oeuvre? Here Ruth Fine, Curator Emeritus in the Department of Modern Art at the National Gallery of Art, answers this question.

Norman Lewis was an inveterate reader, whose library included texts on the materials and techniques of paintings, studies of ornament and architectural traditions, African, Asian and Mexican art, Indian art of the United States, as well as Georgio Vasari’s landmark text on the history of Western art, Lives of Painters, Sculptors and Architects. He also owned many books on modern masters ranging from Paul Cézanne through Georges Rouault, Pablo Picasso, and Alexander Calder. Lewis’s library and his frequent trips to New York museums, especially the Museum of Modern Art, were the most important source of the artist’s visual education.

Lewis’s paintings and works on paper are varied in subject and style. He generally worked in loosely defined series, each of which focuses on a particular motif and/or compilation of artistic processes. Together these groupings contributed to his unique meditation on the diverse possibilities of painting. Lewis’s art conflates figuration with abstraction and juxtaposes forms rooted in both nature and Cubist-inspired geometry. Some works rely on extensive linear components; others, like Prehistory, combine subtle suggestions of line with a range of color-shapes and soft tonal areas.

Lewis likewise explored a diverse palette and an extraordinary assemblage of painterly methods. Throughout his half-century-long career he created works that employ primary and secondary hues (red, yellow and blue; or green, violet and orange, respectively—always subtly mixed by the artist rather than directly from tubes of paint as manufactured). Among his works of the 1960s specifically are stark black and white or red and white calligraphic compositions suggestive of Ku Klux Klan marchers. Prehistory highlights concerns of a decade earlier: an emphasis on abstraction; thinly painted and softly modeled forms with few defining edges; and a limited color range—browns, blacks, and grays, with contrasts of salmon hues.

Lewis probably created the jagged triangular shapes and other defined areas suggestive of facial features and animal forms by masking out some areas of the canvas while leaving adjacent areas open to accept the paint, which he applied with a dry brush, possibly rubbed on with a rag, or using a combination of both methods. Many of Lewis’s titles are now lost, but those that are known, such as Prehistory, offer important information about Lewis’s broad interests. The color, soft forms, and suggestions of animals all call to mind the caves of Altimira in Spain and Lascaux in France which were discovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, respectively. Other titles have Civil Rights themes, for example, or mention plants such as pussy willows and rhododendron, and seasons—spring, winter, and autumn.

Note by Ruth Fine to The Dayton Art Institute, September 26, 2014.

Want to hear more about Norman Lewis from Ruth Fine? Listen to her podcast “A Sense of Place- Norman Lewis in Harlem: ‘An Inquiry into the Laws of Nature’” archived at the National Gallery of Art website here.

Look Around

About the Artist

A Portrait of the Artist as Young Man

From a young age Norman Lewis was determined to become a painter. In an interview art critic and former director of the Community Gallery at the Brooklyn Museum, Henri Ghent, conducted at the Archives of American Art, Lewis talked about this decision and its challenges.

Henri Ghent: “Were either of your parents artistic?”

Norman Lewis: “Neither one. I always wanted to be an artist. I remember at 9 years old there was some Negro woman who used to paint and I used to constantly see her in the street and I used to look and look and look. I always wanted to be an artist, you know, the drawings that children make in the street and stuff like that. I remember coming home and I said to my father that I wanted to be an artist and he said this is a white man's profession. It is a starving profession. He never encouraged me, but musically they forced my brother's becoming a violinist and he was good. And yet visually they couldn't understand my desire to be a painter, you know, which I pursued on my own. And feeling as I did very inferior about becoming an artist, despite the fact that I eventually got a scholarship to the John Reed School, which I didn't attend. I taught myself, which is […] a long way of going about it, because there are shorter ways of discovering what you are.”

(“Oral history interview with Norman Lewis, 1968 July 14,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

Talk Back

Art and/or Activism?

While he worked hard to advance the status of African-American artists and was engaged in the Civil Rights Movement, Norman Lewis believed that art should transcend politics. He said:

“For many years I…struggled single-mindedly to express social conflict through my painting. However, I gradually came to realize that certain things are true; the development of one’s aesthetic abilities suffer by such emphasis; the content of truly creative work must be inherently aesthetic or the work becomes merely another form of illustration; therefore the goal of the artist must be aesthetic development and, in a universal sense, to make in his own way some contribution to culture….”

What do you think about this statement? Does a masterpiece lose something if it becomes too political?