The Changing Face of Buddhism

How has your appearance changed over time? As Buddhism spread from India into East Asia, the appearance of the Buddha often changed, sometimes in subtle ways, other times more drastically. But some things remained the same, such as the drive of artists to communicate the message of the Buddha with power and grace.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Chipping Away at It

How do you transform stone from a rough, shapeless form to a smooth shape with refined features, such as this head of the Buddha? There are a variety of tools sculptors use, many of which have stayed the same for thousands of years. Learn about some of these in the following video from the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts.

Copyright Minneapolis Institute of the Arts

Selected Transcript:

I’m going to show you the tools for stone carving first, and then we’ll take a look at how each are actually used in a demonstration. The first thing that every stone carver needs is a hammer. … You want a heavy hammer so that the weight of the hammer does all the work. The first chisel that you would use is called a point…. It has a sharpened point at one end, and this is for rough work, for roughing out the general shape of your piece. The next step would be to use the claw, or tooth, chisel to refine that rough shape that you blocked out with the point. This particular example has three teeth, and when this is used it will create raised ridges of material. The next step would be to remove those raised ridges with a flat chisel…. Once all of the ridges from the claw, or tooth, chisel have been removed, you would refine that shape with a rasp and also a riffler; these are like files. And then the final smoothing would be done with a variety of grades of sandpaper. …

So the first tool I want to demonstrate is the point. … You kind of have to crosshatch your marks to remove the amount of material that you want to remove. As you get experience you learn how to angle those crosshatches so that you remove just the amount that you want to remove; you don’t want to end up chipping off something that will become the tip of your nose! The next tool…is the claw, or tooth, chisel. This one has three teeth, and it would be the next stage after using the point to rough out a shape. You use the tooth chisel to begin to refine that shape. The next step would be to use a flat chisel to smooth out all the ridges caused by the claw, or tooth, chisel. [Then], remove all the marks made by the flat chisel with a rasp. Quite a bit of finished detail is actually done in this stage. This is the riffler; this particular one has a flattened side, much like the rasp, and then a curved, rounded side with a point, which allows you to get into fine details and really work on removing the striations created by the variety of chisels we’ve used before. … After filing...the next step would be to remove the tool marks from the files with a variety of grades of sandpaper. And the final, polishing stage—if you wanted a high polish—would be to use wet-dry paper like this with a paste made from boric acid.

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

At the museum, you can see many different types of Buddhas. Some Buddha sculptures are similar while others are very different. What might these similarities or differences mean about the artists who created them, or the communities they were created for?

Look around the Asian galleries. There are similar sculptures posed in meditative positions, trying to achieve a state of peace. If this Buddha had a full body, what position do you think the hands and feet would be in? Would it be like the others in the galleries or different? Decide and pose your own hands and feet like that. Or sketch the pose by using other sculpture as reference.

Signs & Symbols

Why does the Buddha have a ringlets?

In many sculptures and paintings of the historical Buddha he has short, curly hair. Why is this? Before he became the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama was a prince and in the fashion of the times he had long hair. After seeing the suffering of the outside world he decided to give up his luxurious lifestyle and live simply, searching for enlightenment. One expression of this was cutting his hair. The Buddhacarita, an early life of the Buddha written in poetry, describes the event like this:

Then, from Chándaka’s [his servant] hand the resolute prince took the sword with the hilt inlaid with gems; he then drew out the sword from its scabbard, with its blade streaked with gold, like a snake from its hole.

Unsheathing the sword, dark as a lotus petal, he cut his ornate head-dress along with the hair, and threw it in the air, the cloth trailing behind— it seemed he was throwing a swan into a lake.

As it was thrown up, heavenly beings caught it out of reverence so they may worship it; throngs of gods in heaven paid it homage with divine honors according to rule.

Aśvaghoṣa, Life of the Buddha, translated by Patrick Olivelle (New York: Clay Sanskrit Library, 2008), 6.56–59.

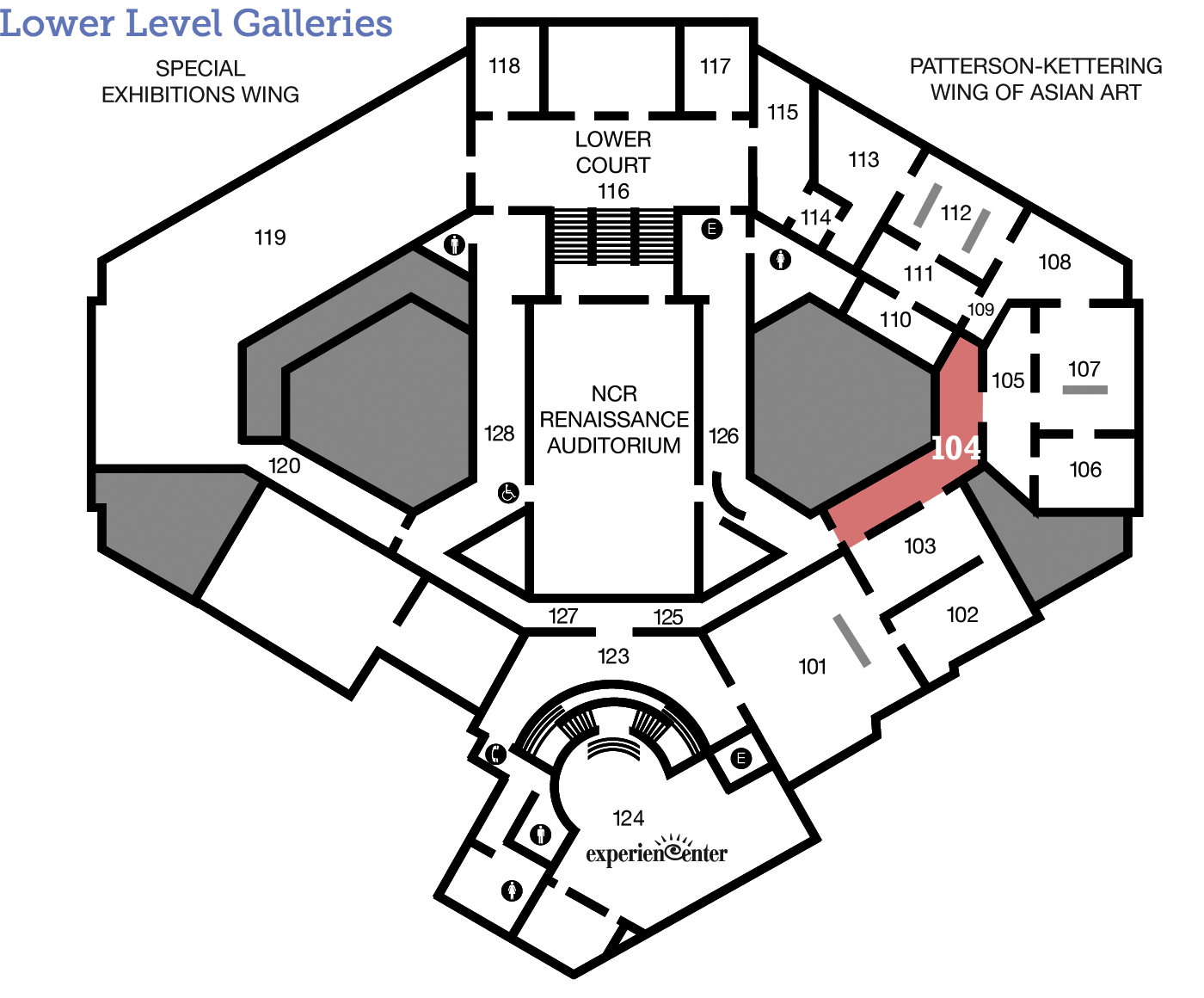

But the Buddha is not always depicted with tight, curly hair. Especially in early sculptures from the Ghandaran region of India he has wavy hair. You can see an example of this in Gallery 115. Notice also that the fleshy bump on the top of the Buddha’s head (called an ushnisha, a sign of his wisdom) appears more like a bun of hair in the earlier Ghandaran Buddha.

Indian, Head of Buddha, 2nd century CE, grey stone, height: 7 inches. Gift of Mrs. Virginia W. Kettering, 1986.232.

Dig Deeper

Mystery Kingdom, Magnificent Art

This sculpture is in the Mon-Dvaravati style. It refers to a unique artistic style that appeared in north-central Thailand between the seventh and ninth centuries among a group a people that spoke the Mon language. Dvaravati is the name of a kingdom in this area that ruled for a period of time, but very little is know about it apart from the art that remains. While early Mon-Dvaravati Buddhist sculpture reflects the influence of Indian styles, a local version developed that incorporated physical traits from the indigenous people.

Quiz

What are the distinct stylistic features that help us identify this as a Mon-Dvaravati sculpture?

A. Large, curled hair.

B. Thick lips, raised at the corners.

C. Large, arching eyebrows joined at a flat nose.

D. Wide, prominent cheekbones.

Answer: Trick question! All of the above.

The Mon-Dvaravati style was one of the first East Asian cultures to create a Buddhist art that departed from Indian styles; for example, compare this with the sculpture pictured in "Signs & Symbols". Other unique features include a distinct asexuality and a symmetry formed by having both hands performing the same gesture. You can get a sense of these in the image below. While most Mon-Dvaravati Buddha sculptures are standing, we cannot be certain if the body this head belonged to originally was.

Further reading: Jean Boisselier, The Heritage of Thai Sculpture (New York: Weatherhill, 1975) and Kurt Behrendt, "The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-Central Thailand“, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mond/hd_mond.htm (August 2007).

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Sacred Stone

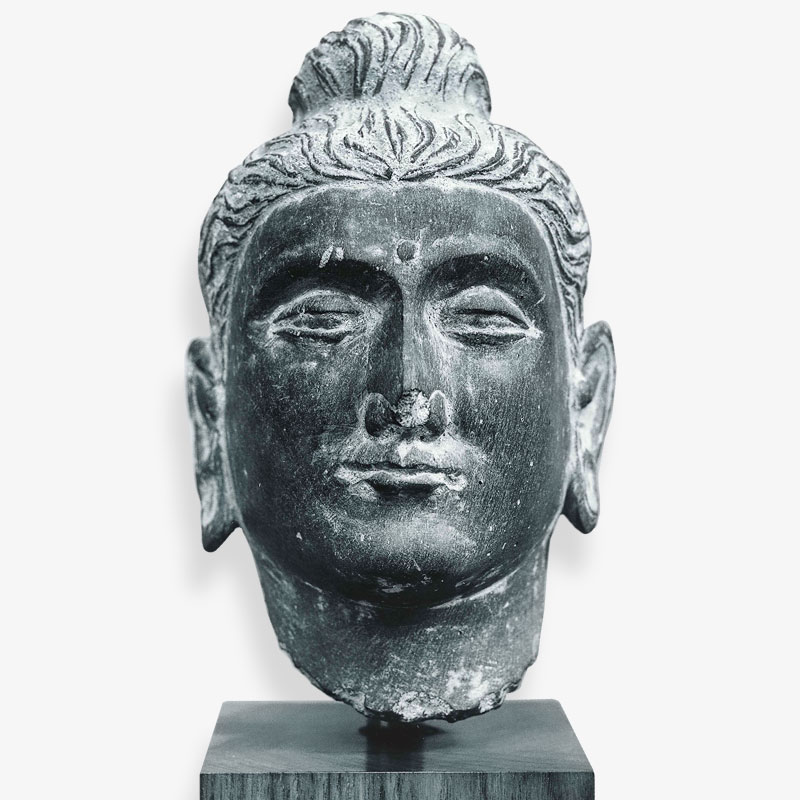

The history of art is closely related to the history of religion, and religious institutions and adherents have often served as important patrons of the arts. In the past, Buddhism was a central topic of Thai art, just as Christianity was in European art. Compare this head of the Buddha with The Dead Christ, upstairs in Gallery 220. Both are fragments of larger stone sculptures, and the faces are a similar size. Look closer at both and explore how the facial features are depicted, noting the similarities and differences. Consider how these features, in a visual way, may help communicate the messages of the Buddha and Jesus Christ, especial the importance of compassion and overcoming what causes human suffering.

Cristoforo Solari (attributed to) (Italian, active 1489–1527), The Dead Christ, c. 1500, marble, 27 x 12 ¾ x 7 ½ in. Museum purchase with funds provided by the 1971 Associate Board Art Ball and the Virginia V. Blakeney Endowment, 1970.29.

About the Artist

Talk Back

Talking Head

This head is a fragment, broken from its body long before it came into The DAI’s collection. Fragments are often seen as lacking something, as less-than-perfect. Does this sculpture suggest other, perhaps positive, ways of thinking about fragments? What might these be?