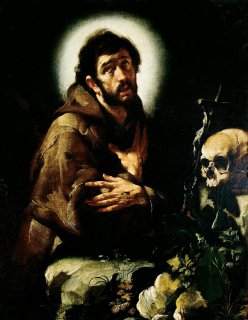

Bernardo Strozzi

St. Francis in Ecstasy

(1581–1644)

Italian c. 1615–1618 Oil on canvas 46 ½ x 35 ½ inches Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Price, Jr. 1966.1

Passionate

Is this man feeling pleasure or pain? How can you tell? With dramatic lighting and bravura brushwork this painting conjures up St. Francis of Assisi, a figure who challenges injustice, mediocrity, and selfishness of every kind.

A Day in the Life

A Saint among Saints

Who is the man in this painting? St. Francis of Assisi (1181/1182–1226) is probably the most beloved saint in Christianity, and even outside Christianity. He embraced a life of total poverty and service to all, opposed violence, and is famous for his joy and love of nature, including preaching to animals. In 1211 he established the Order of Friars Minor, which came to be known as the Franciscans.

Quiz

Franciscans are recognizable by their costume, a simple brown robe with a rope belt that has three knots tied in it. Can you guess what the knots represent?

Equality, Freedom, and Justice.

Truth, Beauty, and Love.

Poverty, Chastity, and Obedience.

Simplicity, Friendship, and Non-violence.

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

No Ordinary Nails

Look at the hands of St. Francis. Does anything look different? This painting depicts a miraculous moment in the life of Francis. He had a vision of an angel and Jesus Christ on a cross; then Francis received the same marks of Christ from the crucifixion: nail marks on his hands and feet and a wound in his side. Known as the stigmata, Francis carried the wounds for the last two years of his life. The event symbolized his full identification with Christ, whom he tried to imitate throughout his life.

Why do the nails on the back of his hands look unusual, like “U” shapes? An answer lies in the early biographies of Francis written by Thomas of Celano (1185–c.1260) and St. Bonaventure (1221–1274). Celano’s version, written two years after Francis’ death, describes the wounds like this:

“His hands and feet seemed to be pierced by nails, the heads of the nails appearing on the inside of his hands and the upper side of his feet, and their points protruding on the other side. On the palms of his hands these marks were round, but on the outer side they were longer, and there were little pieces of flesh projecting from the surface which looked like the ends of nails, bent and hammered back.”

Quoted in: Thomas of Celano, The First Life of Saint Francis of Assisi, translated by Christopher Stace (London: Triangle, 2000), 96.

Detail.

Just for Kids

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

A Faithful Artist

Who was Bernardo Strozzi and how does this painting figure into his career? What details may suggest for whom the painting was made? Find out more in the following commentary by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Curator of European and American Art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College.

Bernardo Strozzi enjoyed a prosperous thirty-year career working for prominent patrons during a period of enormous wealth and cultural significance in the flourishing international port city of Genoa in northwestern Italy. After starting his artistic career as a cloistered Capuchin friar, Strozzi obtained permission to re-enter the secular world and soon established himself as a leading painter in Genoa.

Strozzi depicted the medieval saint St. Francis of Assisi (1181/1182–1226) far more frequently than any other subject, religious or secular, and these images are notably consistent in composition and content. The Dayton Art Institute’s St. Francis in Ecstasy is typical of Strozzi’s presentation of the saint as a solitary figure engaged in ecstatic prayer or adoration before a crucifix and skull. As a Capuchin friar, Strozzi would have been intimately familiar with the significance of St. Francis, who strove to emulate Christ in every aspect. According to early biographies of the saint’s life, St. Francis was fasting and praying on Mount La Verna, in the Tuscan Apennines, when he was overcome by a vision of Christ on the cross and received the stigmata, the marks of Christ’s crucifixion, on his own body.

This painting’s carefully orchestrated composition uses strong contrasts between light and shadow and richly applied layers of paint to encourage the viewer to contemplate every detail of this fundamental Franciscan image of devotion. The outcropping of rocks and plants, upon which the skull and crucifix rest, identifies the location as La Verna, and St. Francis’s spiritual ecstasy is conveyed through the ethereal halo of light around his head, his upcast eyes, and the prominent display of the nails in his hands. While some of Strozzi’s images of St. Francis in prayer show only wounds in the saint’s hands—such as the version at the National Gallery of Art [see below]—the Dayton painting shows the protruding nails with their pointed ends bent back, as they were described in the biography of St. Francis written in 1263 by the Franciscan theologian St. Bonaventure (1221–1274) and widely distributed in the 14th century. This detail suggests that Strozzi was specifically referencing this text, which was revered by the Capuchins as one of the few texts permissible to read along with the Bible. The veneration of St. Francis was widespread by the seventeenth century, but this detail may suggest that the painting was made for a patron or institution allied with the Franciscan order.

Bernardo Strozzi (Italian, 1581/1582–1644), Saint Francis in Prayer, c. 1620/1630, oil on canvas, 45 ¾ x 33 11/16 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Gift of Joseph F. McCrindle, 2002.78.1 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by The National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution).

Look Around

Picturing Piety

For centuries, a common subject of European art was saints, important figures from Christian history. Known for their pious lives and devotion to Jesus Christ, saints are examples to be imitated and visual art is an effective way to tell their stories. Look around the European galleries for other examples of saints, such as Mattia Preti’s The Roman Empress Faustina Visiting St. Catherine of Alexandria in Prison and Frans Francken the Younger’s The Crucified Christ Enframed with Scenes of Martyrdom of the Apostles. Consider what features are emphasized in each painting and how these help impress the viewer with the importance of the saint depicted.

With the rise of Protestantism in Europe during the 1500s and 1600s—which largely dismissed the veneration of saints and visual imagery depicting them—and increasing secularism from the 1700s onward, saints progressively became a minor subject for artists.

About the Artist

Talk Back

Facing Death

Why is there a skull on the right side of this painting? It is an example of a memento mori, a Latin phrase meaning “Remember (that you have) to die.” It is a symbolic way of reminding the viewer that they will die, face judgment, and should live virtuously now.

Death was something St. Francis was aware of and even addressed at the end of his life in his famous poem “The Canticle of the Sun”:

“Praised be my Lord for our sister, the bodily death,

From the which no living man can flee.

Woe to them who die in mortal sin;

Blessed those who shall find themselves in Thy most holy will,

For the second death shall do them no ill.”In The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi (New York: Vintage Spiritual Classics, 1998), 117–118.

What are some of the different ways art can help humans process and respond to death? Since art is made of materials that are also decaying, does death, ultimately, have the last word?