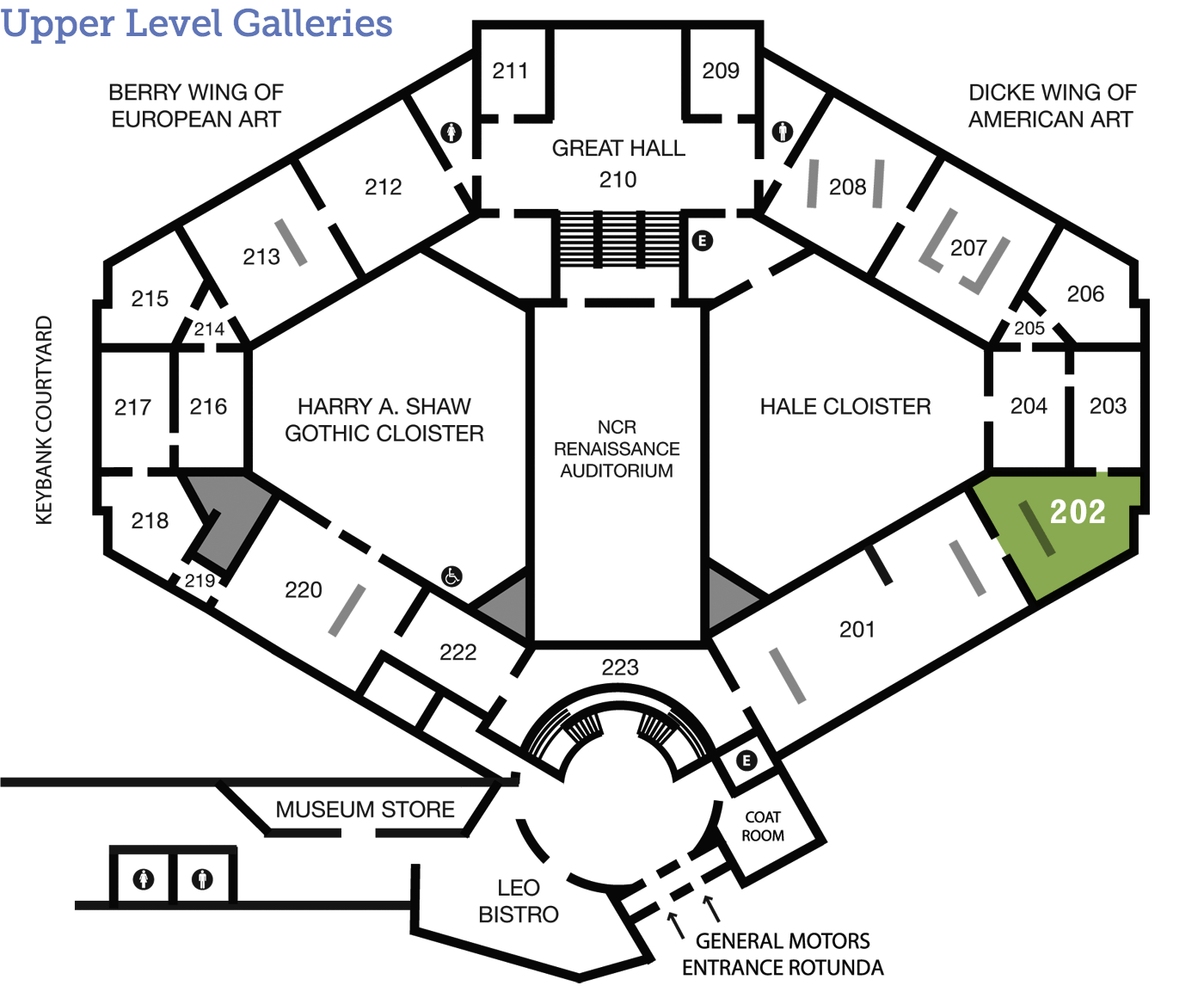

Fairfield Porter

Self-Portrait

(1907-1975)

American 1968 Oil on canvas Museum purchase with funds provided by the National Endowment for the Arts and by Mrs. T. Lawrence Saunders, The Honorable Jefferson Patterson and his late mother Mrs. Harrie G. Carnell, the late Mr. Brainerd B. Thresher and the General Operating Fund 1973.55

Painting the Familiar

As both an artist and art critic, Fairfield Porter countered the prevailing trend of abstract art by painting landscapes and domestic settings. Self-Portrait serves as an example of the familiar environments Porter depicted, and challenges us to see where the familiar may become strange.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Imagine!

A self-portrait is an image of someone that is created by that person. Fairfield Porter painted his self-portrait standing in his studio. Look at his expression and pose. How he might have been feeling?

If you were to paint a self-portrait how would you want to pose? Would you smile? What would you wear?

Signs & Symbols

Look at Me

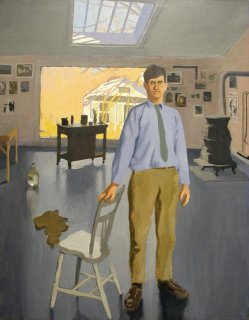

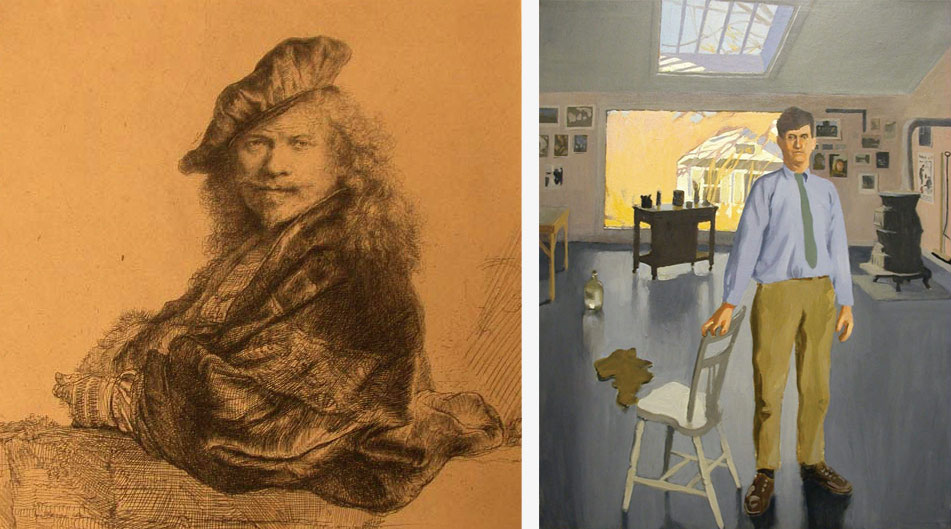

Artists paint many kinds of things. In Europe, for centuries religious or mythological subjects were the most highly regarded, along with portraits of significant people. Occasionally artists would paint self-portraits, but it was Rembrandt who raised the self-portrait to a significant subject in its own right. He made multiple self-portraits throughout his career as a means of studying himself and confronting viewers with his individuality, as if to say, “I am here!” Below, you can see one of Rembrandt’s self-portrait etchings in The DAI’s permanent collection (not currently on view).

Painters have often found the self-portrait to be a convenient subject, as it allows an opportunity to communicate something about themselves, not to mention they did not have to pay model fees since they were the subject! In Self-Portrait, Fairfield Porter made a conscious decision to show his personal studio. What do you think he may be trying to communicate about himself in this painting?

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669), Self-Portrait Leaning on a Stone Sill, 1639, etching and drypoint on paper, ii/ii states, 6 3/8 x 6 5/16 inches. Bequest of Anne E. Charch, 1984.26

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Artist as Critic

Fairfield Porter was not only a successful artist, but he was also a prolific art critic. He wrote many reviews for the magazines The Nation and ARTnews, and these show a great sensitivity to the art of his time as well as broader questions about what art is. One painter Porter admired, and was friendly with, was Willem de Kooning. Find de Kooning’s Untitled in this gallery and then look at the painting through Porter’s eyes by reading a selection of his writing on another painting by de Kooning. Tap on the image below to identify some of the similar details Porter describes.

They represent nothing, though landscape, not figures or still life, is suggested. The colors are intense—not "bright," not "primary"—but intensely themselves, as if each color had been freed to be. The few large strokes, parallel to the frame and at V angles, also have this freed quality. So does the simple organization, the strange but simple color, the directions and the identification with speed. And in the same way that the colors are intensely themselves, so is the apparent velocity always exactly believable and appropriate. There is that elementary principle of organization in any art that nothing gets in anything else’s way, and everything is at its own limit of possibilities. What does this do to the person who looks at the paintings? This: the picture presented of released possibilities, of ordinary qualities existing at their fullest limits and acting harmoniously together—this picture is exalting.

In Fairfield Porter, Fairfield Porter: Art in Its Own Terms, edited by Rackstraw Downs (New York: Taplinger Publishing Company, 1979), 36–37.

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Pondering Porter

Look closer at the colors, the light, and the shapes in this painting. What are the techniques that go into creating this apparently casual composition? What can we learn about the painter and his art through them? Find out in the following audio clip with Carol Nathanson, Professor Emeritus of Art History at Wright State University.

Transcript:

The DAI’s 1968 painting by Fairfield Porter shows the artist in his studio at his home in Southampton, Long Island. A studio is of course that magical place where an artist converts experiences and feelings into a work of art. It makes sense too that an artist would include his or her work environment in a self portrait, because it’s so much a part of that individual’s identity.

Light effects are always important to Porter, seen in The DAI painting in the patterns created by the skylight, in the backlit table, and in the reflective surface of the floor. The DAI’s painting shows immense feeling for the purely visual—for the abstract—in its harmony of greys, browns, and ochers, and its exploitation of geometric form and structural effects. You’ll want to notice how sets of lines produce a vertical connective that runs through the entire composition, beginning with the skylight, continued in the table near the window, and ending in the chair in the foreground.

The highly effective arrangement of lines, shapes and colors we find in Porter’s paintings were never set up by him. He pointed out that he simply discovered existing situations that he thought would make for an effective painting. In his interview with Paul Cummings, he discusses The DAI’s painting as an example of this. He says: “All I did was to arrange that chair for me to put one hand on. The rag on the floor was there and I liked it.” Porter told Cummings that form “is discovered, it’s the effect of something unconscious.” He maintained that if you didn’t consciously think about form but simply remained alert visually, you’d find it.

Look Around

Critical of Critic

During the mid-century many New York-based artists became interested in exploring the expressive qualities of paint by using gestural brushstrokes or broad fields of color. They made mostly abstract images and were generally known as “Abstract Expressionists.” Although he was familiar with these trends in art, Fairfield Porter decided there was still a lot to explore in figurative art. In a 1968 interview, the year he made this painting, Porter talked about why he chose to make this kind of art. It was, in part, a response to influential critics like Clement Greenberg who thought the only interesting art was abstract.

He said: you can’t paint figuratively today. I thought, if that’s what he says, I think I will do just exactly what he says I can’t do. That’s all I will do. I mean, I might have become an abstract painter except for that.

In “Oral History Interview with Fairfield Porter, 1968 June 6,” Archives of American Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution), http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-fairfield-porter-12873.

Look around at other paintings in Gallery 202, such as Norman Lewis’ Prehistory or Mark Rothko’s Untitled. Consider how you might see Porter’s painting differently if it were in a gallery full of other portraits instead of being surrounded by mostly abstract paintings.

About the Artist

Talk Back

Figure It Out

Throughout history artists have depicted the human figure. Fairfield Porter continued to paint figures, such as this Self-Portrait, even though many other of his near contemporaries turned to abstract art (see “Look Around”). As you walk through other galleries in The DAI, notice how artists in different times and places depict the human figure. Why do you think this has been a popular subject for artists? How does seeing a person depicted in art enhance your understanding of what it means to be human?