Clara Driscoll

Dragonfly Lamp

(1880–1930)

American c. 1910 Leaded glass and bronze 27 x 20 ¼ x 20 ¼ inches Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family in honor of David and Lynn Goldenberg 2001.48

No (Dragon)fly on the Wall

Have you heard of Tiffany Studios? What about the name “Clara Driscoll”? This Dragonfly Lamp was designed by Driscoll, an Ohio-born artist who research has recently revealed as the mastermind behind many of Tiffany’s most profitable products. Learn about her talents as well as the contributions of numerous other women who worked at Tiffany’s in the tabs below.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Get Real

How does one spot a fake? After 1902 most Tiffany shades were given a label and the bases were stamped with a model number, however these are not dependable identifiers. Due to the popularity of Tiffany lamps, the market is flooded with forgeries and antique lamps with fake Tiffany labels. In fact, in 2001 the art dealer Reyne Haines, who you may know from the popular PBS program Antiques Roadshow, realized that a Tiffany lamp we had owned was a reproduction, and soon after we replaced it with an authentic piece.

Quiz

Guess which features are more likely the attributes of a real Tiffany lamp.

Question 1:

Glass that is somewhat loose and rattles in its frame.

Glass that has been tightly assembled and makes no noise when you shake it.

Question 2:

Glass that maintains its color when illuminated.

Glass that changes color when you turn on the lamp.

Question 3:

Lamps that are prone to tipping due to their heavy shades.

Lamps that remain upright when softly nudged.

Detail, shade, Tiffany label

Detail, base, Tiffany label and model number

Just for Kids

Look!

Working together as a team Clara and her coworkers designed, cut glass, and assembled lamps, like this one, at Tiffany Studios. The glassmaking studio opened in 1885. Carefully look around this gallery. What do you notice about the glass lamps and vases?

Nature was the inspiration for Tiffany Studios, especially plants and insects. The next time you are outside or taking a walk look at the nature around you. What in nature would inspire you to make your own lamp?

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Working “Girls”

What was it like to be a woman working for Tiffany Studios in the late 1800s? Listen to the following audio clip to find out, narrated by Sharon Howard from the Dayton chapter of The Links, Inc.—a professional organization of women dedicated to enriching the cultural life of African Americans and other persons of African ancestry.

Tiffany Girls on the roof of Tiffany Studios, c. 1904–1905. The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, 2009-012:001 (photograph © The Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, Inc.; photograph provided by The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida).

Transcript:

The Women’s Glass Cutting Department at Tiffany Studios opened under Clara Driscoll’s direction in 1892. Driscoll’s employees—who were all unmarried (Mr. Tiffany refused to employ married women)—produced windows and mosaics in addition to lamp shades.

Their outstanding performance quickly resulted in heated disputes with the unionized male glasscutters at the Tiffany factory in Queens, as the “Girls”, who were unable to join a union, completed their orders at an incredible pace, often working overtime to meet deadlines. Soon the men threatened to strike if the women did not stop making windows, and ultimately a cap was set on the total number of women that Clara could employ. Despite these gendered workplace tensions, the wages of Tiffany’s female employees equaled the men’s, a highly unusual company policy at a time when women typically earned about 40% less than their male counterparts. Find out how the “Girls” made their lamps so efficiently here.

According to Clara’s letters, she and the “Girls” followed these steps when making their shades:

- Clara would first create a paper cartoon, or preliminary design for a lamp. Often busy with her managerial duties, she typically enlisted others to paint her cartoons.

- Then she ordered plaster forms, painted them to look like the shades in her cartoons, and presented these prototypes to Mr. Tiffany for approval. He rarely made changes to Clara’s designs.

- The next step was to create a wooden mold of the shade and sketch the design onto it for reference during the final assembly process.

- The “Girls” then fashioned a pattern made of cloth or brass, placed a clear sheet of glass overtop the pattern, and traced the design onto the glass with black paint.

- Next they selected the colored opalescent glass for the lamp and painstakingly cut and grinded it to match the pattern pieces, attaching copper foil to the edges.

- Once all the cutting was complete, they arranged the opalescent pieces on the clear sheet of glass, following the traced design.

- The glass sheet with the opalescent pieces was sent to the welding department, where men transferred the pieces to the wooden mold and finally soldered them together. The shade was then dipped in a copper electroplate bath and coated with a patina.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Female Power

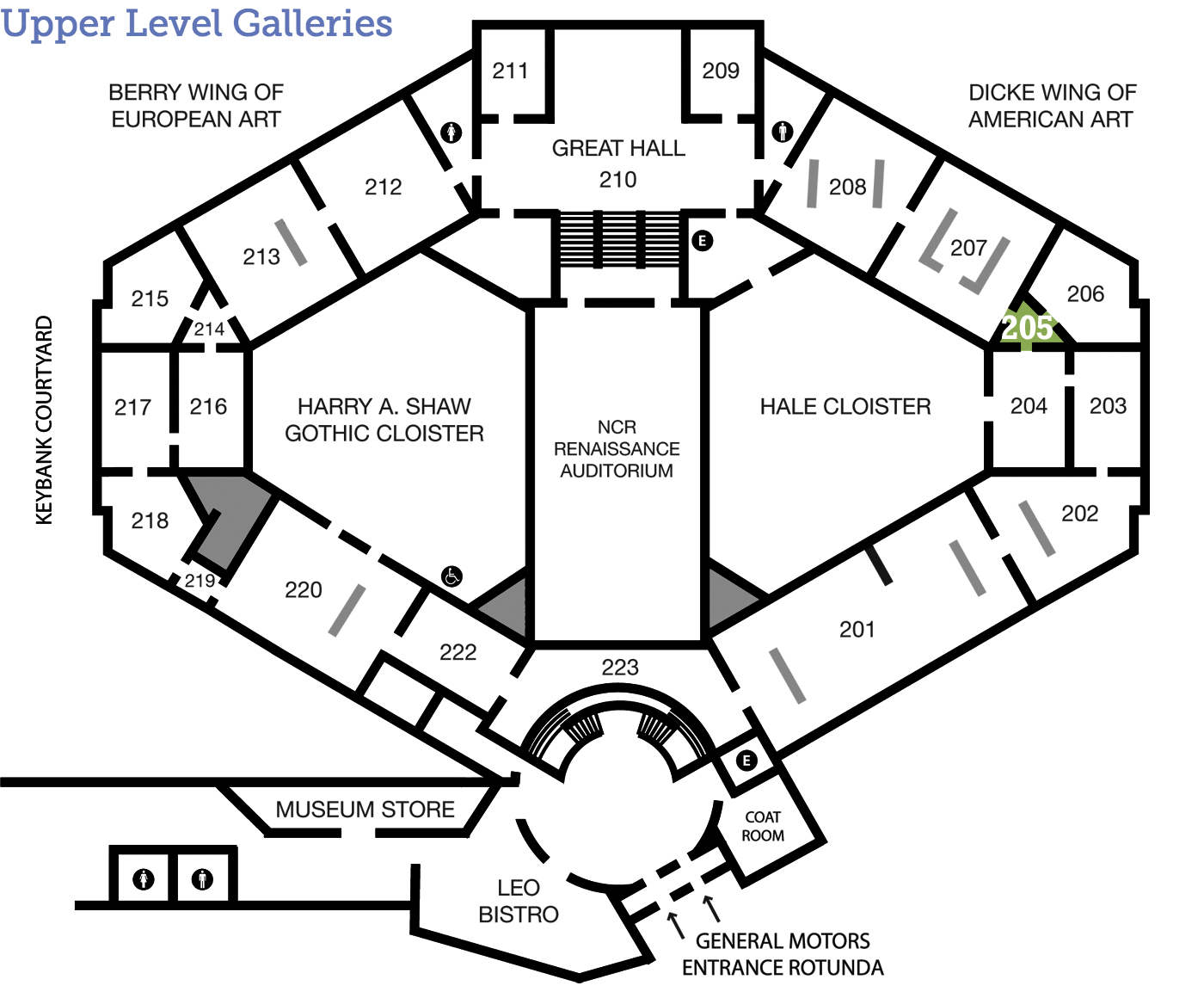

What other female artists are represented at The DAI? Take a look at Joy of the Waters, a bronze sculpture by Harriet Frishmuth in the gallery next door. Frishmuth was a hugely successful artist working in a medium dominated by men, and as a woman her oeuvre subverts the familiar trope of the male artist rendering the female nude.

Harriet Frishmuth (American, 1880–1980), Joy of the Waters, 1917, cast bronze, 63 ½ x 15 x 16 inches. Gift of Mrs. Harrie G. Carnell, 1919.1.

About the Artist

From Local to Luminary

Clara Pierce Wolcott, later Clara Driscoll, was born in Tallmadge, Ohio in 1861. Her learned, widowed mother ensured that Clara and her three sisters were similarly educated, thus Clara attended Western Reserve School of Design for Women in Cleveland and later the Metropolitan Museum of Art School in New York. She first began working for Louis Comfort Tiffany, son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, in 1888, and remained there for the better part of twenty years.

For marketing purposes, Tiffany Studios attempted to downplay the contributions of the gifted designers that worked at the company, emphasizing Louis Tiffany’s artistic direction instead. However, in 2007 scholars examined Clara’s personal correspondence and learned of her considerable influence at the company. Not only was she responsible for the design of our Dragonfly Lamp, but the majority of Tiffany floral lamps produced, like the poppy-motif lamp below. Moreover, the “Tiffany Girls” (as Clara called them) in the Women’s Glass Cutting Department also had significant influence over the final appearance of these objects: they had the freedom to choose the colors and types of glass used and could modify each lamp as needed. Such revelations help amend the deep-rooted masculine bias in art history that long failed to record the name of female artists and considered women’s art inferior.

Further Reading: Gray and Hofer Eidelberg, A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls (New York: New-York Historical Society, 2007).

Table Lamp, Tiffany Studios [probably Clara Driscoll], c. 1902–1938, glass and bronze, 17 x 20 ½ inches. New York Historical Society, N84.55.1 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by the New York Historical Society).

Talk Back

Authentic Admiration

In 2001 we discovered that a “Tiffany” lamp we owned was in fact a reproduction, and we replaced it with an authentic one. For about 10 years, however, our guests admired an object that, while incredibly beautiful, was not a true Tiffany. Would you have been more likely to question the authenticity of a Tiffany lamp if it was located in someone’s home? Why or why not? Alternatively, if you discovered that an antique lamp you owned was not a true Tiffany, would that make it any less worthy of your admiration?