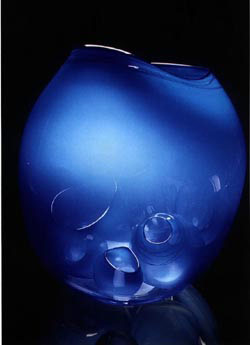

Dale Chihuly

Aurora Red Ikebana with Bright Yellow Stems

(b. 1941)

American 2001 Blown glass Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous donor, John Berry, Sue and Donald Dugan, Warren and Barbara Fryburg, Anne Greene, Bill and Sandy Gunlock, Steve and Sue Libowsky, Elden and June Lindquist, Steve and Lou Mason, Bill and Judy McCormick, Judy and David Montgomery, NCR Corporation, Bob and Linda Nevin, Carol and Richard Pohl, Jr., Violet Sharpe, Frank and June Shively, Doug and Flora Thomsen, Lee and Betsy Whitney, Judy Wyatt, and Bill and Dorothy Yeck, and gift of Mr. and Mrs. T. Hart Fisher in memory of Fredricka Patterson Lewis by exchange 2001.87

Eye Glass

Where have you seen glass today? In the car? In your phone? At breakfast? When does glass become art? Dale Chihuly’s sculptures manipulate glass in a way that encourages us to see it, rather than seeing through it.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Drawing Out Chihuly

Chihuly is best known for his glass sculptures, but he has also made thousands of drawings. These have gone from practical first steps for his glass sculptures to becoming independent objects of their own. Listen to Chihuly reflect on the evolution of his drawings and see examples of them in the following video from the Chihuly Studio.

Chihuly Drawings from Chihuly Studio on Vimeo.

Transcript:

Somebody once said that people become artists because they have a certain kind of energy to release; and that rang true to me. That’s really why I draw. If you look at the history of my drawings you’ll see that they started off in the late [19]70s working with graphite, charcoal—simple things showing the glass blowers how to work. Then they got more complicated. And then the Venetians [glass series], I made drawings that actually looked like the Venetians.

Then I began to add some color, probably watercolors initially, and then liquid acrylics, and then I started painting with the container itself, just squirting the paint out. But I would always have sponges and brushes and mops and brooms around if I wanted to use other implements to draw with. The drawings got wilder and they got larger, definitely less related to the work itself; they became more abstract.

I average several thousand faxes a year. Whatever I do, I do a lot of and I do it fast, it’s just my nature. And I need all of those tools; I need to make a lot of phone calls, I need to make thousands of faxes to distribute my ideas, because as you write a letter, of course, you’re thinking. It’s simply a way to make your mind work, and it’s also putting the drawing or the painting down on paper that helps you sort of figure out what’s in your mind. Of course the scale of the drawings went up all the way along as well. The biggest drawings I’ve been doing are six by eight feet. Actually, I’m using these special dyes that are very much like glass, along with the acrylics, sort of hand-in-hand, and there’s a reaction between the colors.

I think the drawings play a very central role in my creativity. If I didn’t draw I don’t think the work would have progressed at the rate, or in the directions, that the work has gone.

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

Dale Chihuly is a glass sculptor inspired by nature and his years of traveling the world. While traveling in Japan, Dale Chihuly became interested in ikebana. Ikebana is a Japanese style of flower arranging. The simple arrangement highlights the flower’s vertical lines.

Look at the Tiffany Dragonfly Lamp by Clara Driscoll. Describe the similarities or differences between these two pieces.

Clara Driscoll (American, 1861–1944), manufactured by Tiffany Studios (American, 1880–1930), Dragonfly Lamp, c. 1910, leaded glass and bronze, 27 x 20 ¼ x 20 ¼ in. Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family in honor of David and Lynn Goldenberg, 2001.48

Clara Driscoll (American, 1861–1944), manufactured by Tiffany Studios (American, 1880–1930), Dragonfly Lamp, c. 1910, leaded glass and bronze, 27 x 20 ¼ x 20 ¼ in. Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family in honor of David and Lynn Goldenberg, 2001.48Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Art of Arranging Flowers

This glass sculpture is part of artist Dale Chihuly’s Ikebana series. Works in the series contain sinuous glass flowers placed in glass vases. Chihuly drew inspiration from ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging. Flower arranging as an art form has been practiced for centuries in Japan, and there are numerous schools that each have their own method, from the traditional to the modern. What do typical ikebana flower arrangements look like? What can you learn from doing ikebana? Get a sample in the following video from the Missouri Botanical Garden with Yoshiko Mitchell, chairperson of the Japanese Festival Ikebana Program.

© Missouri Botanical Garden

Transcript:

The recorded history of ikebana as a recognized art of flower arrangement was recorded a little over 550 years ago. But by the time of 550 years ago, of course, it was already there. Then, many masters defined ways of teaching everybody. We ikebana people look at every material, the meaning of every plant and flower. Not just the flower’s face is beautiful, but every part of the material is good.

One nice thing about ikebana—if you start learning ikebana—you learn all about the plant and how to use good water for the plant. In other words, you will learn all about your surroundings and the time of season. And that lets you know, well, everybody has winter, spring, summer, and autumn; any living things, that’s what you learn. And then you can use all these flowers just like a painter uses paint.

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Serial

Throughout his career, Dale Chihuly has often worked in series, creating many objects around the same basic pattern or theme. Aurora Red Ikebana with Bright Yellow Stems is one example from his Ikebana series. Other series include Cylinders, Baskets, and Macchias. Look around Gallery 123 for some examples of these in The DAI’s collection. (Note: Oxide Blue Basket Set with Flint Lip Wrap is not currently on view).

Blanket Cylinders

Chihuly’s first experience with glass was weaving the material into tapestries as a student, and this sparked his interest in traditional weaving designs. Inspired by geometric designs from Navajo blankets, Chihuly produced this series over a two-year period.

Dale Chihuly (American, b. 1941), Navajo Horse Blanket Cylinder, 1976. 1998.33.

Jerusalem Cylinders

With the Jerusalem Cylinders, Chihuly used stone-shaped glass attached to cylinders as symbols of the ancient city.

Dale Chihuly (American, b. 1941), Metallic Sand Jerusalem Cylinder, 1999. 2001.86.

Baskets

A Northwest Coast Indian basket Chihuly saw at the Washington State Historical Museum in 1977 inspired the Basket series.

Dale Chihuly (American, b. 1941), Oxide Blue Basket Set with Flint Lip Wrap, 2000. 2001.46.

About the Artist

Taking It to the Limit

For over 40 years Dale Chihuly has explored the potential of glass and tested its limits. In 1976 he lost the sight in one eye in an auto accident, and this affected his depth perception. Partly as a result of this, Chihuly began to work with a team of glass blowers, and this expanded further the size and scope of what he could do with glass. Learn more about what drives his work—and see his team in action—in the following video from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Then look around Gallery 123 further and investigate how other artists have used the material of glass.

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Transcript:

So you take sand and fire and put it together and you have glass. It turns into a liquid; imagine the sand turns into a liquid and then you stick a pipe in there and gather it up like honey and bring it out and blow down there and you blow a shape that, over the centuries, glassblowers have learned to make it into an incredible array of forms. And I’ve been lucky enough to come along at the right time, at the right place, to be able to expand many of the forms that were made throughout this 2000-year history. I was using just human breath going down into this miraculous material, blowing it up, pushing its limits, making it as thin as I could, getting it so hot that it would almost collapse and begin to move. So I was pushing the edge of thinness and collapsibility and making new forms. The Baskets did evolve into the Sea Forms, and the Sea Forms evolved into the Persians. A series like the Venetians will come in, which are totally different. Or the Chandeliers came out of nowhere. It requires a totally different type of thinking; we’re not talking about objects here, we’re talking about twelve or fourteen hundred pieces of glass making one object.

Really, what I’ve always been interested in is space. Even when I made the Cylinders, the single-object cylinder, or the Macchias, my interest was always in space. So I was thinking not of the object itself, but how the object would look in a room. The Chandeliers don’t really relate to that evolution of the Baskets, Sea Forms, Persians, probably, so, as an artist I just make, I just work, things just come out. It’s not that you’re constantly searching for something new, it’s just that something new comes.

I don’t know why I work so large. I very often push a series to its maximum size. I think sometimes I do it just to keep the glass blowers at the very edge of their technical ability, to keep the tension high, to make it exciting, to make it so that we don’t know whether it’s going to break or not break. If you know exactly what you’re doing and you can make it every time, it’s not going to be interesting. It has to have this tension if the pieces are going to be good, and so we constantly push ourselves. I push them, they push me; I try to get them to go beyond what they can do. It’s more interesting that way.

Talk Back

Art Director

Traditionally, making glass requires a team effort, and this is central to Dale Chihuly’s recent work as he directs his team of artists through drawings and coaching. Throughout history, many artists have used assistants to produce artworks, from 18th century portrait painters such as Joshua Reynolds to modern artists such as Andy Warhol or Sol Lewitt. You can see works by these artists in Galleries 213 and 201.

Why might one artist get credit for a work when a team made it? What are other jobs or professions where a similar situation occurs?