Louise Nevelson

Untitled

(1900-1988)

American 1985 Wood and black paint Museum purchase with funds provided by the James F. Dicke Family 2003.7

The Art of Recycling

What a difference a coat of paint makes! Calling herself “the original recycler,” Louise Nevelson assembled found objects she painted a monochrome color into assemblages that invite you to see something new in something old.

A Day in the Life

Stampede!

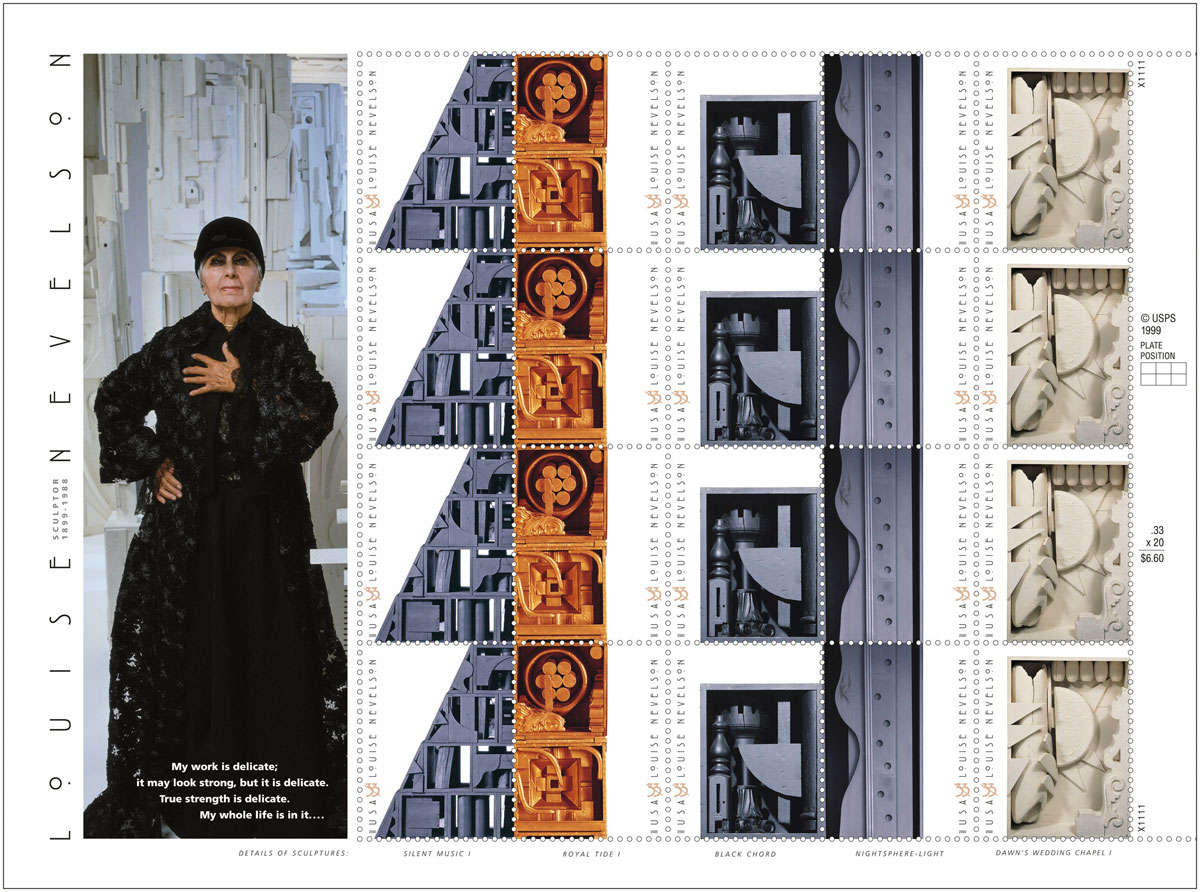

In April 2000, the United States Postal Service released a commemorative sheet of stamps in honor of Louise Nevelson, who died in 1988. It included five different sculptures and a photo of her.

How is a person selected for a postage stamp? A panel called the Citizen’s Stamp Advisory Committee reviews proposals for new stamps (anybody may submit one) and they give recommendations to the Postmaster General, who makes the final selections.

Quiz

Can you guess which artist has not appeared on a postage stamp?

Romare Bearden.

Frida Kahlo.

Fairfield Porter.

Georgia O’Keeffe.

Edward Hopper.

© 2000 United States Postal Service, Louise Nevelson photo by Arnold Newman

Tools and Techniques

Tossed and Found

Look closer at the different pieces of this sculpture. Do any of the shapes look familiar? From the 1940s Louise Nevelson began to pick up discarded pieces of wood she found around her home in New York, from large objects to small scraps. She would typically paint these monochromatic—usually black, white or gold; occasionally bold colors—assemble them in boxes of different sizes, and stack them into larger units. Sometimes she made whole room installations. Why was Nevelson attracted to what most people considered useless? She said:

I began to see things, almost anything along the street, as art … That’s why I pick up old wood that had a life, that cars have gone over and the nails have been crushed … All [my] objects are retranslated—that’s the magic. … I think what people call by the word scavenger is really a resurrection.

Quoted in Paul Richard, “Nevelson and Her Fabled Shadows,” The Washington Post, April 19, 1988.

Another artist who recycles old materials is Alison Saar. Look for her sculpture Lost and Found in this gallery. Nevelson and Saar’s use of found objects from daily life recalls the “readymade” artworks of Marcel Duchamp and challenges what we think an artwork should be made of and how it should be made. Does knowing that the materials in these objects had a previous life change how you see them? Consider why this might be.

Alison Saar (American, b. 1956), Lost and Found, 2003, wood, tin, and wire, 28 ½ x 125 x 33 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the 2004 Medici Society, 2004.16.

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

Louise Nevelson lived in New York City. Outside her home she noticed trash and began to pick it up. Recycling scraps and reusing found objects Louise Nevelson created large assemblages, or three dimensional collages of found materials.

Looking closely at this sculpture, do any of the shapes or objects seem familiar? Can you tell what they were once used for?

Have you ever used recycled materials when creating art? Louise Nevelson called herself the original recycler. To create your own assemblage, combine various materials together like Louise Nevelson did. Gather and arrange scraps of wood and metal, buttons, paper, lids, bottle caps, fabric or any other recycled objects. Use glue to attach all the materials together.

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Nearby Nevelson

There is a public sculpture by Louise Nevelson outside the main branch of The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Sky Landscape II was originally commissioned in 1980 for the headquarters of the Federated Department Stores (now Macy’s). It was later given to the city and moved to its current location in 1993. The painted steel sculpture weighs 3800 pounds and stands 20-feet tall.

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Louise Nevelson Sees You

If you are in the gallery looking at Nevelson’s sculpture, look over your left shoulder. There is a portrait of Louise Nevelson by the New York artist Alison Van Pelt. Van Pelt has made large-scale portraits of important women artists from the 1900s. Other artists in the series include Helen Frankenthler and Joan Mitchell, and you can see examples of their work in this gallery.

Look closer at Van Pelt’s painting of Nevelson and consider how it may echo some of the features of Nevelson’s sculpture.

Alison Van Pelt (American, b. 1963), Louise Nevelson, 2001, oil on canvas, 108 x 84 1/8 inches. Gift of Paul Rusconi, 2004.13.

About the Artist

Self-Centered

Louise Nevelson challenged conventional perceptions of what a woman artist should be like, and what kinds of materials should be used in an artwork. What was the focus of Nevelson’s work? Find out more by listening to Nevelson herself and some of the people who knew her in the following excerpt from the film Nevelson: Awareness in the Fourth Dimension by Dale Schierholt.

© Dale Schierholt

Show transcript.

Selected Transcript:

Louise Nevelson: If we recognize what we are made of, and how we are made and put together, the rest is an extension. And I can still go back to say that it’s your consciousness and your awareness of all this. So, all that I have said is—all along the line—that I don’t want to make anything. What I am doing is living—the livingness of life—and using all these things to extend this awareness.

Laurie Lisle (Biographer): She really overturned any stereotypes about the nature of the work of women artists. …

Marius Peladeau (Former Director, Farnsworth Art Museum): She was a hard-drinking, hard-living woman who didn’t want to be dragged down by all these supposed, perceived, old-fashioned stereotypes of the weak, submissive, obedient, disciplined woman. …

Louise Nevelson: My whole life has been centered—you can use the word self-centered if you wish, I think it’s a great word, who am I going to center myself on if not on my inner self? …

Marius Peladeau: There are very few artists who are comfortable with no color; black is the absence of color. And very few artists are comfortable working—they need the blue, green, yellows, and reds to be able to carry forth whatever their vision or their impression is of what they’re looking at. Louise was looking inside her and she wasn’t seeing color, she was seeing ideas and concepts; philosophical ideas, emotional reactions to something in her life or to something that had happened on the street, so that the color was not necessary for her to bring forth an emotion—the emotion was more in the structure that she was creating.

Robert Indiana (Artist): You know, it might be discarded toilet seats and wooden boxes from the street, but she managed to transform all of that into something very moving and very beautiful.

Rufus Foshee (Nevelson Scholar): She made sense, and order, and solidity out of chaos. Those strewn objects along the street became these beautiful moving objects once they went through the transformative hands and eyes and heart of Louise Nevelson.

Talk Back

Paint It Black

All the pieces in this sculpture are painted the same shade of black. What does this suggest to you? Louise Nevelson made many sculptures like this that were painted all black. However, she also made others that were gold or white (for one example from the Whitney Museum of American Art, click here). How might a different color change the way you sense and respond to this work?