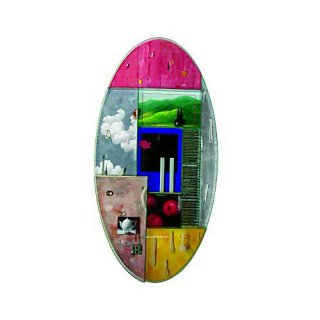

Therman Statom

Ovala Marea

(born 1953)

American 2004 Assembled glass with blown glass fragments and painted mixed media 146 x 74 x 9 ¼ inches Museum purchase with funds provided by the Medici Society 2006.26

Self Reflection

What do you see? In Ovala Marea, Therman Statom draws on items and imagery that relate to his personal identity and fashions them in plate glass, aluminum, and an oval shape that evoke the materials and shape of a mirror. What is reflected back?

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Just for Kids

Look!

Therman Statom combines different materials and colors in Ovala Marea. What materials do you see in Ovala Marea. If it helps, look carefully and list all the different materials being used. How heavy do you think the sculpture is? Do you think you could carry it?

Signs & Symbols

More than the Sum of Its Parts

Tap on the highlighted parts below to learn about the different materials and images used to create Ovala Marea—as well as some interesting facts—based on Statom’s correspondence with The Dayton Art Institute.

Dig Deeper

What Does It All Mean?

Therman Statom combines multiple mediums and images to create works with a dream-like quality that almost beg the question, “What does it mean?” Statom himself is not sure. As he says, “Because of the many, many influences and references…it is difficult to specify what the painting is about. I try to address an emotional essence that relates more to our intuitive sensibilities rather than the intellectual.”

This can make interpreting Ovala Marea challenging, but also exciting. How do you put all the different pieces together? Sharon Howard, from the Dayton chapter of The Links, Inc.—a professional organization of women dedicated to enriching the cultural life of African Americans and other persons of African ancestry—shares her own ideas in the video below. Listen and then compare it with your own perspective.

Transcript:

The beauty of art is that it allows each individual person to lose him or herself in any given piece, and then they can escape and create all kinds of stories and visuals for themselves. When I look at this piece by Statom the first thing that captivates me is his use of color. He uses bright jewel tones which would attract any person, even if the piece was across the room. Reds, greens, blues, and yellows; all vibrant colors that would immediately catch the eye of an art lover. But then when you peel back the layers of the color, you see all of the abstract that he uses. And it is interesting because we have landscapes, we have clouds, we have what appears to be windows that you can peer through. And then somewhere embedded into all of that we have apples, and we have a tea pot. And it screams and begs the question, “What in the world was he thinking? And so, I have no clue what he was thinking…but that is the beauty of art, because it can be whatever you want it to be.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

Studio Glass

Therman Statom is part of the Studio Glass Movement, which emphasizes glass as an artistic medium rather than a purely functional one. Artists working within this context have shown the multiple possibilities of glass. For example, compare Ovala Marea with Dale Chihuly’s Aurora Red Ikebana with Bright Yellow Stems and Jon Kuhn’s Bold Endeavor, both in Gallery 123.

Chihuly works with hot, blown glass while Jon Kuhn uses cold-worked glass that is cut, laminated, and polished. Statom takes a third path, combining these processes and assembling sheet glass into sculptures that he blends with other materials. Consider how these various techniques help you experience color, shapes, and even the pure material of glass differently.

Dale Chihuly (American, born 1941), Aurora Red Ikebana with Bright Yellow Stems, 2001, blown glass. Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous donor, John Berry, Sue and Donald Dugan, Warren and Barbara Fryburg, Anne Greene, Bill and Sandy Gunlock, Steve and Sue Libowsky, Elden and June Lindquist, Steve and Lou Mason, Bill and Judy McCormick, Judy and David Montgomery, NCR Corporation, Bob and Linda Nevin, Carol and Richard Pohl, Jr., Violet Sharpe, Frank and June Shively, Doug and Flora Thomsen, Lee and Betsy Whitney, Judy Wyatt, and Bill and Dorothy Yeck, and gift of Mr. and Mrs. T. Hart Fisher in memory of Fredricka Patterson Lewis by exchange, 2001.87.

Jon Kuhn (American, born 1949), Bold Endeavor, 1998, laminated, cut, and polished glass, 9½ x 24 x 6 inches (glass), 24½ x 45¾ x 8½ inches (base). Museum purchase with funds from the James F. Dicke Family, 1999.29.

About the Artist

Crossing Borders, Blurring Lines

Therman Statom creates works of art that challenge clear distinctions. He crosses mediums, using a variety of materials such as plate glass, hot- and cold-worked glass he blows and shapes himself, paint, pencil, and even found objects from daily life. He crosses space, sometimes making works that hang on a wall, such as Ovala Marea, but also creating immersive installations, rooms of glass that envelope the spectator. How does Statom describe his own work? Watch the following video from the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington, to hear his own words.

All rights reserved. ©2011. Museum of Glass.

Transcript

I’m Therman Statom and I’m from Omaha, Nebraska. I’m a painter-sculptor. I’m trained in the craft of glass blowing; I’ve sort of evolved from that. I actually still use glass blowing in the work, but I do public art. I guess by public art I mean installations; I do temporal ones at institutions and cultural centers, and I also do permanent things—like airports or libraries—permanent sorts of applications. I’m a big fan that any event that happens in anyone’s life or anything that can be resourced from within can be used as an inspiration. I might respond to a particular environment aesthetically in an ergonomic way, or physically in an ergonomic way; but it really varies a lot. I do also work with art therapy and I use art as a tool for advocacy. So a lot of times that advocacy issue is explored in the artwork.

I’m here at the Museum of Glass and I’m working on a multiple range of projects. [To workers: “Because I want to do so many different kinds of things, I’m open to suggestions as we go along.”] On a more personal level, I’m also exploring my own ideas in glass and sort of innovating with this team of people here and figuring out things that I haven’t made before. [To worker: “We’ve got money. Just a slight bend and we’re good.”] They’re understanding my flexibility and form and making decisions while we’re blowing; it’s really great. [Worker: “It’s asymmetrical.” Statom: “Yeah, it is.” W: “Maybe we can flatten it so it’s no longer round, but I do not know if that’s—“ S: “No, no, when it bends it’s going to move.”] We are making parts for a whole range of projects; some of them local, some of them national, and some of them for a show that I am doing at the Ebeltoft Museum [in Denmark]. There’s an element of the unknown, hopefully, that we have to contend with in each piece. It’s an element I’m going to use in a painting; obviously, it’s a crystal ball. I don’t have specific metaphors or meanings for objects; they’re done more from impressions, and I think to tell you the source ideas or what I’m thinking could be misleading, in that the language of painting and objects is a visual language and an intuitive language; there might be some intellectual references, but I think people spend too much time looking for those. I think they need to learn to trust that they can understand art and what things mean in reference to who they are. It’s great to be here; it’s an interesting environment to work in, sort of like being in a big nightclub. There’s the lights above and this multi-floor space. [To workers: “Raise the roof!”]

Talk Back

Meaning-less or Meaning-more?

The diversity of materials and images in Ovala Marea allow for many interpretations, instead of one simple “meaning.” Why might the meaning of artworks change over time? Does a work of art have more value for you if the meaning seems open-ended?