Hughie Lee-Smith

Woman in Green Sweater

(1915–1999)

American c. 1957 Oil on canvas 18 x 24 inches Museum purchase with funds provided by the 2002 Associate Board Art Ball 2002.34 202

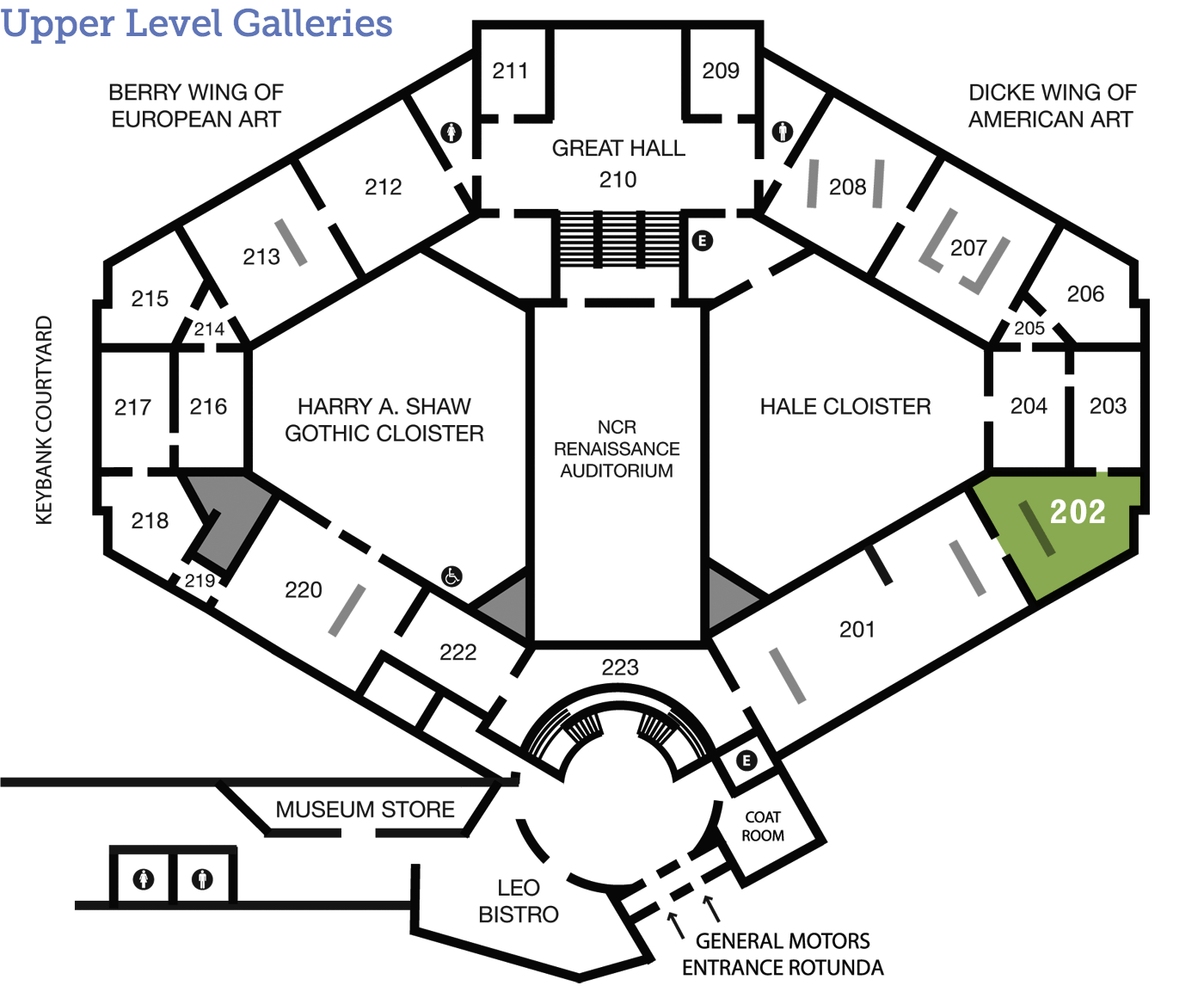

Going Solo

What causes loneliness? The color of one’s skin? Faceless technology that pervades more and more aspects of life? Acutely aware of the challenges of living in modern America, the African-American artist Hughie Lee-Smith blended realism with dream-like passages, creating paintings that provoke a search for meaningful connections.

A Day in the Life

Tools and Techniques

Behind the Scenes

Look Closer

Seeing the Shadows

Hughie Lee-Smith studied art at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), where he received a strongly classical art education, focusing on the fundamentals of drawing and painting from the nude figure. One of the technical aspects that fascinated Lee-Smith from the beginning was chiaroscuro, the relation of light and dark values in a painting to create dramatic contrast. Chiaroscuro is most associated with the Italian Baroque painter Caravaggio, whose dramatic use of light and dark influenced many painters in 17th-century Europe, such as Bartolomeo Manfredi, whose work is in The DAI’s permanent collection.

Hughie Lee-Smith directly learned chiaroscuro from his teacher Carl Gaertner at the Cleveland School of Art. An example of Gaertner’s work that shows the complex interplay of light and dark is his Gravel, Fish, and Soya Beans, seen below. Now, look closer at Woman in Green Sweater. Consider how Lee-Smith’s use of light and dark contrast affects your impression of the painting.

Carl Gaertner (American, 1898–1952), Gravel, Fish, and Soya Beans, 1947, oil on fiberboard, 28 x 48 inches. The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., Bequest of Henry Ward Ranger through the National Academy of Design, 1962.10.5 (photograph provided by the Smithsonian American Art Museum).

Just for Kids

Imagine!

Some paintings can tell a story. In Hughie Lee-Smith’s painting Woman in Green Sweater, who is this woman and why is she alone? Pretend you are a journalist and this painting is your news story. Investigate the painting carefully to gather all the information. Write a brief newspaper article. Be sure to answer these questions: What happened? Who was involved? Where did it take place? When did it take place? Why did it happen?

After you have completed the article share the story with your friends.

Signs & Symbols

Dig Deeper

Encountering Existentialism

Hughie Lee-Smith's paintings of solitary figures in vast, bleak landscapes, such as Woman in Green Sweater, emphasize the fundamental aloneness of people (see “About the Artist”). In this way, they evoke the philosophy of Existentialism. Listen as Diane Dunham, Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Dayton, explores this philosophical perspective further. There are many ways one can experience Woman in Green Sweater, but does your thinking change when considering the painting through the lens of Existentialism?

Transcript:

In 1945, twelve years before Hughie Lee-Smith painted Woman in Green Sweater, the French existentialist thinker Jean Paul Sartre made his first visit to America. World War II had just ended, and the revelations of large-scale ethnic cleansing, as well as the destructive power of the atomic bomb presented humanity with some deeply troubling questions about itself and its future.

It was before, during and after World War II that a body of thinking known as Existentialism developed largely in France, and most famously by Sartre. Existentialism begins with the only thing any of us begin with, and that is existence itself. And when we find ourselves in existence—are “thrown” into it, as Sartre phrased it—we also find ourselves in a world that does not seem to provide us with a user manual, instructions or messages embedded within it that tell us what it all means, what’s behind all this, and most importantly, what are we supposed to be doing.

But to begin with the ground of existence is to recognize that nothing can “precede” it, for to speak of something that “pre-exists” makes no sense, linguistically or otherwise. There is only existence, and this is wherein each and every one of us finds ourselves, collectively and individually. And in so doing, each of us faces the same world that appears indifferent to our human efforts, and bereft of any inherent meaning. If nothing can precede existence, then nothing could be said to have been planned: not for us, or even us ourselves. It is into that universe indifferent to our struggles that human beings must create both an identity for themselves, as well as a meaning for their lives. Sartre and existential philosophers like him drew strength from this absurd condition in which we find ourselves and set forth an ethic of human freedom and an activist stance about how to pursue that.

But this existential moment—this realization of nothing larger than ourselves to lean upon and no universe of purpose or meaning to tell us what to do—this is a defining realization for existential thinkers, and perhaps also a moment to which nearly every human being can relate: we find that we are nothing, inherently, against the gigantic and mute universe going about its silent business; we find that we have need to become something in those circumstances, anyway. And in such a scheme, humans have only themselves, their choices, beliefs and actions—conscious or otherwise—to credit or blame for the condition of the human world. Listen also to “About the Artist” for Hughie Lee-Smith’s own words about the creative power of solitude and isolation, in his works and in his life.

If you would like to compare your own thinking with Diane Dunham’s reflections on Woman in Green Sweater in relation to Existentialism, tap below to hear more.

Show more.

Transcript:

It is a short distance in cultural time and space from these foundational thoughts of Existentialism to Hughie Lee-Smith’s Woman in Green Sweater. Here, too, we have the solitary individual ensconced in a suggestively vast landscape; and here, too, we seem to have a setting wherein the contemplative human being is doing its contemplation without any help from the mute and indifferent surroundings. Even the pier pilings she stands near speak of small human achievements against the power and enormity of the sea. This woman in a green sweater, much as another foundational existentialist thinker, Søren Kierkegaard, once put it, stands in “absolute relation to the absolute”—the All, the Totality of existence—with nothing to mediate or interpret her life for her, most especially another human being. We cannot enter the isolation of her subjectivity, except to remember our own.

Not every painting that exhibits the vastness of nature and the human being’s relative smallness in comparison can be seen as “existential” in the foregoing sense; for example, romantic landscape paintings such as one of Albert Bierstadt’s, also here on display at The Dayton Art Institute in Gallery 207. His Scene in Yosemite Valley also renders living creatures small if not invisible against the beauty and grandeur of nature, but the nature Bierstadt paints is rich with presence, power, hidden meaning and mystery, as though answers surely lie somewhere in existence, perhaps just beyond the valley fog.

Albert Bierstadt (American, 1830–1902), Scene in Yosemite Valley, 1864–1874, oil on canvas, 20 7/8 x 29 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Daniel Blau Endowment Fund, 1976.58.

Unlike traditionally romantic landscapes, an existential landscape and the solitary individual are in a confrontation of sorts: each of us might have asked on the dark night of the soul: what am I; what should I be; what should I do; what’s this all about? But the universe makes no replies. Rather than nature standing taller than the individual as in romantic landscape painting, the individual is simply standing alone from the existential point of view. Yet out of that aloneness do each of us do the hard labor of carving out an identity for ourselves and a meaning for human existence, against a universe that appears indifferent to our efforts. Woman in Green Sweater can be seen through this existential lens as just such a confrontation between the solitary individual and the Totality, the All. And Hughie Lee-Smith’s surrounding landscape can be seen as this languid and indifferent vastness within which this woman does, and therefore has to, confront her existential reality. Our responsibility for our self-creation is both a terrorizing moment of isolation, as well as the springboard for all future possibilities.

Arts Intersected

The Sculpture Speaks

Did You Know?

Expert Opinion

Look Around

All the Lonely People

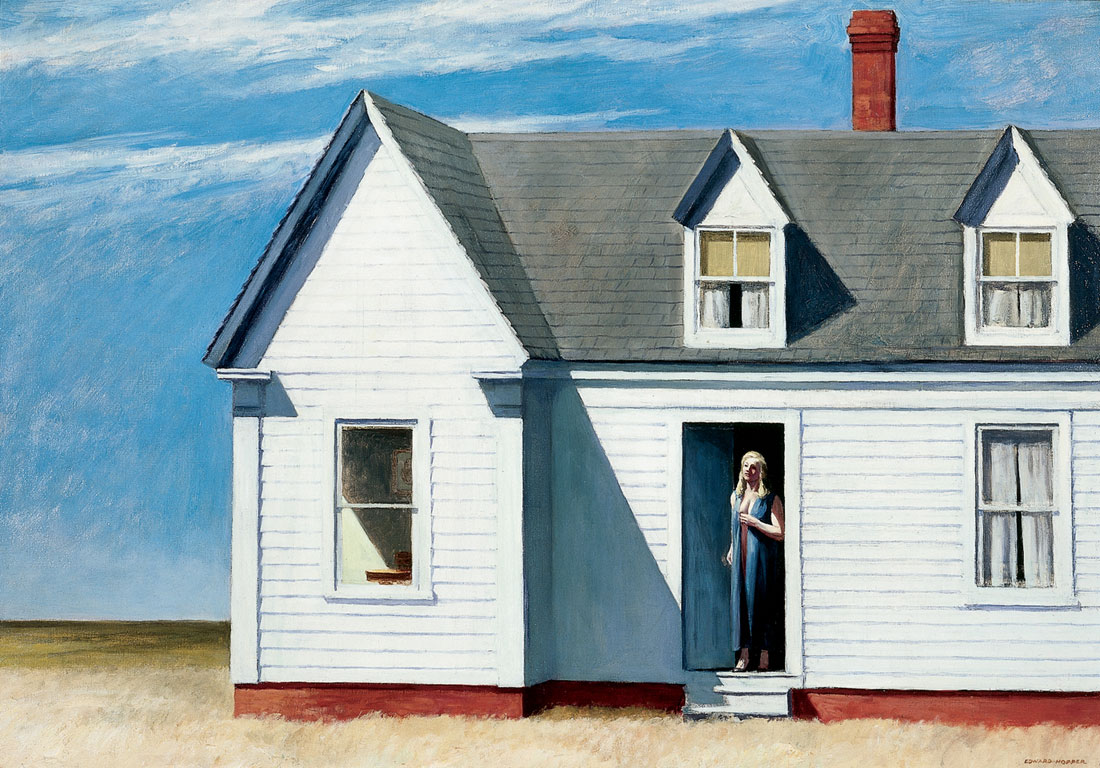

Hughie Lee-Smith’s paintings often show individual figures isolated in a large space. Another American painter known for images of solitary people is Edward Hopper, whom Lee-Smith admired. Compare Woman in Green Sweater with Hopper’s painting High Noon in Gallery 204, including the setting, pose and costume of the figures, and the uses of color, light, and line.

Poll

Overall, do you think these paintings are more similar or more different?

Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967), High Noon, oil on canvas, 1949, 27 ½ x 39 ½ inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Howell, 1971.7.

About the Artist

From Isolation to Independence

Loneliness and isolation are themes repeated throughout Hughie Lee-Smith’s work. This concern was, in part, shaped by Lee-Smith’s experience as an African American. Listen to Lee-Smith’s own words on the challenge of race and its relation to being an artist, read by Sharon Howard from the Dayton chapter of The Links, Inc.—a professional organization of women dedicated to enriching the cultural life of African Americans and other persons of African ancestry.

Transcript:

In my case, aloneness, I think, has stemmed from the fact that I’m black. Unconsciously, it has a lot to do with alienation. The condition of the artist is already one of aloneness. Our work depends upon being alone, and we can appreciate the condition of aloneness more than other people. Being one of a group of outcasts in a society makes my sensitivity to the condition of aloneness much sharper than that of the average person. There is an isolation that every sensitive person feels; it is something all creative people recognize. And in all blacks there is awareness of their isolation from the mainstream of society. I felt it much more in my youth. Now I am not so affected by the alienation because I can appreciate my independence as a human being.

Quoted in Carol Wald, “The Metaphysical World of Hughie Lee-Smith,” American Artist 43 (October 1978), p. 101.

Talk Back

Signs of the Times

During a time when explorations of abstract and conceptual art were cutting edge for artists and critics, Hughie Lee-Smith persisted in creating images of isolated people. This was, in part, his way of responding to the modern world as he saw it. As he said, “This was simply my way of emphasizing the widespread condition of loneliness that prevails in our materialistic society. In a situation wherein there is a breakdown of the family structure, where there is racism and a suffocating technology, there exists a sort of generalized fear and sense of alienation. Hence, I sought to project this emotion by situating the single figure in overwhelming space.”

The theme of alienation in Lee-Smith’s work is rooted in his own particular experience, yet it also speaks to a universal concern common to all humans. How were variations of alienation pictured in previous eras? What about our own era? To what extent is art an attempt to overcome alienation, or alternatively, embrace alienation?

Quoted in “Interview with Hughie Lee-Smith,” in Clarence Holbrook Carter and Hughie Lee-Smith: Two Master Painters (Summit, N.J.: New Jersey Center for Visual Arts), p. 13.